지붕의 정치경제학: 1970년대 한국의 새마을운동*

The Political Economy of the Roof: The New Village Movement in 1970s South Korea*

Article information

Abstract

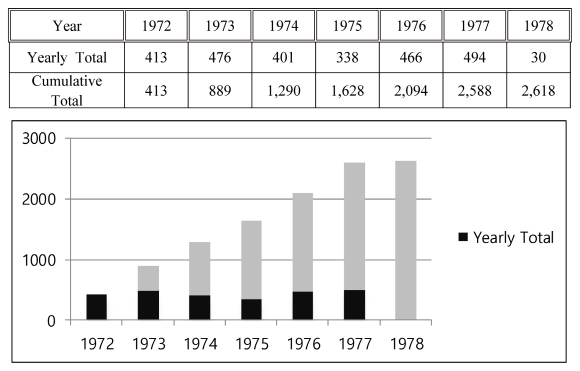

이 연구는 1970년대 급격한 산업화 시기에 ‘새마을운동’이라는 이름으로 진행된 한국의 농촌 근대화 사업을 살펴본다. 특히 이 새마을 근대화 프로그램 중 '지붕개량사업'이라는 특정 프로젝트에 초점을 맞추고 있다. 흔히 1970년대 한국 농촌의 빈곤은 빛바랜 초가지붕이 가득한 단색조의 마을 풍경 이미지로 표현되곤 했다. 따라서 낡은 초가지붕을 좀더 화려하고 현대적인 것으로 교체하는 것은 농촌 발전을 보여주는 가장 효과적이며 극적인 방법 중 하나로 여겨졌다. 지붕개량사업의 결과로 1978년까지 농촌 전역의 초가집 약 2,618,000채가 낡은 지붕을 ‘신소재’ 슬레이트로 교체하는 놀라운 일이 벌어졌다. 농촌의 이러한 변화는 특히 고속도로를 따라 늘어선 화려한 색상의 슬레이트 지붕을 통해 두드러지게 나타났다. 농촌공간이라는 캔버스에 전시된 강렬한 원색은 궁극적으로 군사정권의 취약한 정당성과 그 개발정책의 성과를 선전하는 듯했다. 그러나 새로운 ‘현대식’ 지붕은 실제로는 농민의 경제적 궁핍을 더욱 악화시키고 특정 산업의 자본 축적을 강화하고 있었다. 이 연구는 이렇듯 불균형한 자본의 흐름을 추적하기 위해, 새마을 지붕개량사업을 통해 초기 축적의 기반을 다질 수 있었던 한국의 두 기업집단 KCC그룹 및 벽산그룹의 1970년대 경영 활동의 양상도 살펴보고 있다.

Trans Abstract

This study investigates South Korea’s rural modernization project conducted under the name of the New Village Movement during the rapid industrialization period of the 1970s. The focus is on a specific event called the Roof Improvement Project within this Movement. In the 1970s, rural poverty was often portrayed through images of monochromatic village landscapes populated by dilapidated mud-walled houses crowned with coverings of faded grass thatch. Replacing the thatched roofs with something more colorful and modern was quickly identified as one of the most effective ways of showcasing ‘rural development.’ By 1978, an astonishing 2,618,000 thatched houses throughout the countryside had their old roofs replaced with a new material known as ‘slate.’ The rural ‘change’ particularly manifested through the brightly colored slate roofs lining the highways. This technicolor display propagandized development and, ultimately, legitimized the military regime’s rule. However, the new ‘modern’ roofs actually eroded farmers’ financial status and bolstered the accumulation of capital by specific industries. To trace the flow of capital extracted from farmers, this study also delves into the history of two large corporate groups - KCC and Pyŏksan - that were able to solidify the early foundation for their current business formation in the 1970s.

Introduction

1) The New Village Movement and the Political Economy of Space

In 1970, the South Korean state launched the New Village Movement officially for the purpose of addressing the low-income levels in rural villages that lagged behind urban areas throughout the postwar industrialization process.1 The state was able to justify the initiation of this project and urge broad participation by highlighting a spatial image of rural poverty, which contrasted the ‘backward’ status of the countryside with metropolitan wealth. Under the slogan of rural modernization, the Movement thus first undertook wide-ranging construction projects in the countryside.

In the early 1970s, the focus of these construction projects turned to the roofs of the Korean countryside. At the time, rural poverty was often represented through images of a monochromic village landscape populated by dilapidated mud-walled houses crowned with coverings of faded grass thatch. Replacing these thatched roofs with something more colorful and more modmrn was quickly set on as one of the most effective ways of displaying ‘rural transformation’ or the ‘new village.’ By 1978, an astonishing 2,618,000 thatched houses all over the countryside had their old, thatched roofs replaced mainly with ‘Sŭlleit’ŭ (slate),’ which was said to be a perfect technological material for this purpose.2

In fact, this dichotomous representation of the countryside and the city was not a unique phenomenon to the post-war industrialization process of South Korea. It is not difficult to find identical patterns of description of urban and rural spaces in the so-called peasant literature (Nongmin munhak), which flourished especially during the 1930s in colonial Korea.3, Voluminous examples in Raymond Williams’ work, The Country and the City, also inform us of quite similar discourses and episteme about the rural and the urban in England that prevailed since the start of the industrialization process there.4 In my study, the ‘pervasiveness’ of this form of spatial representation finds its root in the mode of existence of industrial capitalism, which is sustained by the circular reproduction of evenness and unevenness in the market.

The diametrically contrasting spatial images highlight unevenness and, by doing so, legitimize the forms of evenness that lead to other layers of unevenness. Arguing for the necessity of reconstruction, the New Village Movement emphasized and reproduced a universal form of binary images and discourses between the wealthy city and the destitute countryside, alluding to the unbridgeable and thus independent existence of these two sectors. However, there had always been exchanges between urban manufacturing and rural agriculture, and the so-called urban wealth was reliant on extracted farmers’ capital from the agricultural sector especially throughout the 1950s and 60s after the Korean War.5 By highlighting only the consequential images of rural poverty, the spatio-visual representations of the countryside and the city concealed the inseparable and exploitative exchange relationship. In this represented disconnection of relationship, the visualized ‘unevenness’ was accounted for solely through references to the low productivity of agriculture and the negligence of farmers. At this juncture, the New Village Movement or the Roof Improvement Project was able to be promoted in the name of “rural modernization,” which itself pointed to the evenness of the city and the countryside. The Movement’s slogan, “diligence (Kŭnmyŏn), self-help (Chajo), cooperation (Hyŏptong),” was actually a proclamation that the movement would be conducted by the farmers’ own labor and funds who were viewed as responsible for their poverty. This was a capitalist way of mobilization in the developmentalist state.

As will be shown in this study, the new slate-roofs, the symbol of modernization and evenness, eroded farmers’ financial status and bolstered the accumulation of capital by particular industries. In this sense, unevenness always took place again at the very moment and position of homogenization or evenness for the continuation and growth of capital. Government officials forced farmers to replace their thatched roofs mainly with slate, often during the busy farming season. Some economists supported the government’s project through their economic evaluation of slate-roofing. They tried to prove that, in the long-term, farmers’ saved labor from annual or biannual grass-roofing would compensate for the slate-roofing cost and eventually turn into profit. This was the moment when the state’s language of economics began to capture previously untabulated labor as a value-added resource to be exchanged in the market. The meager amount of government subsidy led farmers to take out loans, and the farmers’ debt capital – their future labor – flowed into the market in exchange for manufactured slate and other construction materials, like in the economists’ numerical expressions. In order to trace back such a flow of farmers’ extracted capital and exchange relationship, this study delves into the history of two large corporate groups in South Korea, Pyŏksan Group and KCC Group, two Chaebŏls that were able to solidify the early foundation for their current business formation through the Saemaŭl Roof Improvement Project in the 1970s.

2) Alternative Narratives to the New Village Movement

Industrial modernization and developmentalism have long been contentious themes in studies of political economy.6 In this study, I approach these issues from the cultural and aesthetical perspective as expressed through a collection of ordinary and everyday source materials – such as newspaper, peasant magazine, government propaganda, cartoons, and product advertisement.

The Saemaŭl Roof Improvement Project was deeply rooted in the ideologies of development and modernization. The colorfully painted slate-roofs were first placed in the Korean countryside around highways and tourist sites so as to be displayed most prominently. From there they quickly spread all over the peninsula. The primary-colored roofs stood for the ‘changing countryside’ and were intended to give a strong visual impression to passers-by and rural residents. Towards this end, government officials fastidiously controlled the selection of colors and even shades for each farmhouse, considering coloration and coordination with neighboring houses. In this way, modernization and developmentalism were systematically expressed in daily spaces; and the countryside became a kind of ‘canvas’ portraying the colorful legitimacy of the military dictatorship.

What was called ‘change’ was a visual illusion created by farmers’ debts. However, the core of the illusion was not in the presence of the new roofs, but in the absence of the old ones. Around the completion of the roofing project, the government began to emphasize the necessity of preserving thatched roof houses out of fear of their extinction. Government authorities explained that some of thatched roof houses should remain as historical materials for the education of future generations who would be ignorant of past poverty. The discourse of preservation actually intended to proclaim the complete end of poverty; and it was a powerful aesthetic strategy for propagating the government’s accomplishment of modernization.

Of course, state planning did not permeate into the public without resistance. Confronting government officials’ daily badgering, farmers sometimes delayed the roofing intentionally, and in other instances negotiated with the local government to receive more subsidies. As another effective means of indirect resistance, people expressed their aesthetic disagreement over the government’s choice of roof colors. Their criticisms on the beauty and ugliness of the roofs reflected their political positions as well as personal aesthetic views and color tastes. For the farmers at this juncture, the expression of aesthetic taste toward the new roof was a kind of the “weapon of the weak.”7

The New Village Movement was conducted most vigorously in the 1970s until the death of Park Chung Hee in 1979 but continued to remain and evolve up until the present, becoming a constant reminder of the Park regime to contemporary South Koreans. Thus, as countless volumes of government and quasi-official sources demonstrate, studies that focus on what was called the New Village Movement itself tend to conclude with only Park Chung Hee’s leadership and the regime’s efforts at developing agrarian modernization policies.8, Even relatively critical studies dealing with the New Village Movement tend to adhere to the evaluation of the Park Chung Hee military dictatorship in terms of the state’s nondemocratic coercion and socio-economic inequity.9 However, the main aim of this study is not to evaluate the rights and wrongs of Park Chung Hee and the authoritarian state, nor does it intend to further entrench the personality cult that has developed around the man. This study instead focuses on various relationships hidden behind the title of the New Village Movement – the dynamics among the manufacturing capital, state, and farmers.

Also, for those who are too familiar with the historiographical controversy over economic development versus socio-political oppression surrounding authoritarian regimes in the postwar industrialization, this study offers to consider the concrete material context beyond the totalitarian slogans of spiritual values and developmentalist discourses of modernization. In this process of returning to materiality, readers with interest in the scale of historical narratives may also find in this study how effectively microscopic stories can show the different sides that dominant historiographies have not sufficiently explained. A piece of slate can tell us another version of the story about economic growth in South Korea, known as one of late industrializations.

The relationship formed between this small and concrete commodity and farmers explain in detail how fledging entrepreneurs in certain industries endeavored to establish the countryside as a new domestic market and reconfigure the farmers as a promising consumer group. The role of domestic market and farmer-consumers is what mainstream narratives have often ignored while preoccupied with the widely accepted framework emphasizing heavy chemical industries and export-oriented development in the postwar socio-economic history of South Korea.10

“Modernizing” the Roof: The Saemaŭl Roof Improvement Project

1) The Countryside and the City

In South Korea, urban-based manufacturing capital had grown rapidly while farmers had suffered from chronic destitution since the Korean War (1950–1953). During the early industrialization period in the 1950s and 60s, farmers living in rural areas were represented as a suffering collective by comparison with urbanites in the city where non-agricultural industries were concentrated. With increasing frequency starting especially in the late 1960s, the differentiated locations’ relative wealth and poverty was expressed through contrasting images of rural and urban space.

A cartoon in a farmers’ magazine in 1971 represented this paradigmatic contrast between the countryside and the city.11, It illustrated the economic disparity between the rural areas (Nongch’on) and the city (Tosi) with an image of a literally ‘unbridgeable’ construct. In the illustration, the city was figured as a tall concrete skyscraper while the rural areas are shown as a small, thatched roof house. (Figure 1)

In the image, a causeway connects the isolated rural locations with the city; however, this section of the bridge slants precariously downward. This, what the caption calls, “odd bridge” not only fails to function as a passage to the opposite bank, but it also acts as a ramp descending into the water. The dysfunction of the bridge is given an explicitly economic dimension through the visualized imbalance of “GNP,” inscribed on the bottom of the span linking the two constructs. GNP (Gross National Product) had frequently been cited in South Korea as a numerical indicator of ‘development’ and was considered a clear marker of a collective objective: the growth of the national economy. Thus, when the cartoon split the holistic concept of gross national product into the rural areas and the urban areas, there was an underlying assumption that posited a rural impediment to the urban contribution to ‘economic development.’ At this juncture, the cartoon’s meaning did not stop at offering compassion to rural destitution; it also constituted an implicit call for rural areas to be restructured, in other words, to make the bridge passable and to allow for the ideal of a balanced and expanding GNP to be achieved.

This supposed division between the rural and the urban erased the ever-present exchange of capital between the agricultural industry located mainly in the countryside and urban-based manufacturing. The economic disparity between the agricultural industry and manufacturing was the product of the unequal exchange that had existed throughout the post-war industrialization process. However, only images of the explicit material differences, the byproduct of this exchange, were publicly highlighted. This mode of depiction, which bracketed out the countryside from the city, suggested that the poverty of rural areas had been the fault of unproductive agriculture and farmers. Such spatial representations now demanded that the countryside and farmers acknowledge their culpability and undergo self-improvement to catch up with the thriving cities. The New Village Movement of the 1970s relied on such spatio-visual strategies to first target the iconized rural roof, forcing farmers to rapidly replace their thatched houses, the symbol of rural underdevelopment, with their own financing and labor.

2) The Roof Improvement Project

When the government launched the New Village Movement as a comprehensive program for rural ‘modernization’ in 1970, one of the movement’s first steps was to replace thatched roofs in rural villages. In the widespread discourses on economic disparity between the agricultural areas and the city, the thatched roof had been emblematic of rural inferiority. The symbolic and comparative illustration on thatched roofs was resonantly expressed also in the official voices of government authorities overseeing the New Village Movement. The Division of Rural Housing Improvement at the Ministry of Home Affairs published a thick book entitled The Great Construction Project of the Nation (Minjok ŭi taeyŏksa) in 1979. This book offered a wide range of information and documents on rural housing improvements of the New Village Movement in the 1970s. The introduction opened with the following quote: “The symbol of our poverty and despair for the past centuries was the shabby thatched roof house in the rural villages. The village, where thatched roof houses were clustered chaotically and wretchedly near a crooked entrance or narrow inner roads, was a pitiable scene representing the stagnation, underdevelopment, laziness, and fatalism of our rural society in the past.”13 In such a shared portrayal and memory, the single change of remaking straw roofs itself could be a perfect indicator to display the achievement of ‘modernization’ for the rural areas. It could be a clearly visible and powerfully symbolic ‘change.’ Eliminating the thatched roof thus became a top priority target for the New Village Movement.

Eventually, the roof improvement project commenced as a leading task of the New Village Movement in the early 1970s, changing thatched roofs into slated roofs all over the country. At the time, slate was introduced as an excellent technological material for the ‘modernization’ of the countryside. A 1973 article in a business journal extolled the virtue of slate as a construction material, while introducing the growth potential of a slate company: “Slate is very strong, light, convenient, absolutely non-flammable, utterly water-resistant, and non-corrodible by any poisonous gases. Moreover, slate is durable for over sixty years; it is simple to build with, and it saves a large amount of timber and steel frames.”14, Many official documents on the New Village Movement recorded the slate-roofing as the “core project (Haeksim saŏp),”15, “ ig niting project (Chŏmhwa saŏp),”16, or “symbolic project (Sangjingjŏk saŏp),”17, which became “a driving motive and fertilizer for the continuation and acceleration of the Saemaŭl Undong.”18,

3) Roof on the Roof

In the process of replacing thatched roofs across the country, many contentious conflicts happened especially when local officials applied compulsory measures. Roof improvement, as an initial project of the New Village Movement, was conducted on the basis of inter-village competition and became an important criterion for officials’ evaluatio n.21, ‘Saemaŭl officials’ in charge of the New Village Movement were often reprimanded or dismissed for poor performance.22, The pressure put on the Saemaŭl officials was enormous and their deaths and illnesses from overwork were occasionally reported in newspapers.23 This pressing atmosphere explained why local officials’ fervent approach to work was often accompanied by coercive means in contrast to the official proposition that these reforms were all voluntary.

The amount of pressure on local officials and subsequent compulsion in changing rural roofs had a functional relationship with the significance of the project’s symbolism. Extreme cases of conflict between the officials and farmers were thus more likely to appear at places where the symbolic implications of the project could be most efficiently presented. In 1974, officials in Ch’ŏngwŏn County forcibly removed thatched roofs from two farmhouses, which were located on a sight-seeing road near the Mt. Songnisan National Park.24, This led to disaster when a sudden rain caused flooding in the kitchens and rooms of the exposed houses. This incident brought about public reproach on the compulsory execution of roof improvement. The local government stressed that the house owners had been repeatedly urged to change the roofs in accordance with province planning, but they had repeatedly failed to follow the administrative order. Yet, public sentiment was sympathetic to the farm households’ unfortunate situation because the farmers could not afford to replace their roofs due to financial difficulty and now their only means of shelter was heavily damaged by the local government’s “beautification campaign.” A similar case had taken place in the same county two years earlier. In 1972, Ch’ŏngwŏn County sent officials to force the removal of eleven thatched roof houses in the county.25 The demolished houses were located near the Ch’ŏngju interchange, and high-ranking officials were supposed to pass through it to participate in an event for encouraging the agricultural sector. Afterwards, the county offered a small amount of compensation for the demolition with a short comment that the houses had been removed because the area belonged to road allowance. The homeless farmers had to stay at their neighbor’s houses or barns for some time.

Local officials’ persistent demands for the replacement of roofs often ended with absurdities. Some old rural houses were so crooked that it was hard to cover the roof with slates in a straight line. In those cases, more time and money were required to finish the roofing work properly. However, farmers were usually too busy and poor to afford such work. Farmers were also often importunately urged to change their roofs during the busy farming seasons. Abnormal and crude houses were created as a result of farmers’ reluctant reactions to the officials’ importunity. Local villagers coined specific terms to mock such bizarre houses. “Five to six (Yŏsŏt-si o-pun chŏn)” indicated curved new slate houses which looked like a minute clock hand reached at an angle of sixty degrees.26, “Mother in her last month of pregnancy (Maktal agi ŏmma)” and “hunchback pillar (Kkopch’u kidung)” were expressions for distorted houses with the walls of round belly shape which stood out especially under a straight slated roof.27, In 1970, the Tonga ilbo newspaper put a photo alone in the Society section with the title of, “Tiled Roof Overlaying a Thatched Roof.”28, Although the newspaper did not add a detailed article to the photo, the image by itself effectively explained the farmers’ predicament. The picture illustrated how a farmer living beside a road had no choice but to lay tiles over the thatched roof in a makeshift display to save time during the busiest part of the farming season. Such stop-gap construction to pacify officials lasted until the last year of the roof improvement project. In 1978, Sin’an County planned to change eighty-three roofs of a village within a week in order to receive high-ranking central officials visiting to inspect drought relief measures.29 The short notice in the busiest farming season drove the villagers to resort to last minute measures in order to have good-looking new roofs. However, not long afterwards, the villagers had to re-roof the houses because during the pressing schedule of the original construction, the quickly laid earthen layer placed on the roof did not fill enough the gap between slates and ceiling.

Of course, farmers did not always yield to local officials’ will easily. In the final year of the roof improvement project, a bureaucrat who worked in Sŏsan County commented that, “I felt as if I were going into the battlefield when I had to visit the village where I was responsible for roof improvement.”30, For the local official, it was a very stressful experience dealing with “the stubborn” who shouted, “Why do I have to rebuild my roof now? My thatched house has had no problem at all for generations.” Sometimes farmers attempted to negotiate with local officials to receive more subsidies. 184 farm households in Asan County firmly refused to change their roofs, though many officials from different local offices in the county came by turns in an attempt to change their mind and hurry up the construction.31, Reluctantly the county offered to pay all the expenses for improving roofs, and the villagers agreed to it at last. It was also reported that a farmer in the same county caused further trouble by not starting construction even after receiving available loans and subsidy.32

To express aesthetic dissatisfaction was also a very tactical choice by farmers resisting the state’s unilateral projects while avoiding outright confrontation. In 1977, Asan County officials suggested that Buksu-3 village and Kongsu-4 village paint roofs within five colors of dark green, dark grayish-green, greenish-blue, dark red, and scarlet “to blend in their surroundings.”33 To supervise the county office’s ‘suggestion’ for each household, an official visited a Mr. Yi’s house in Kongsu village and recommended that his roof be painted in dark red color to match the neighboring houses. Yet, the color did not suit the taste of Mr. Yi’s wife. She intensely objected to the unwanted color leading to the “embarrassment” of the county official. It is not known if the woman eventually submitted to the official’s administrative color sense or firmly maintained her taste for coloration.

Facing such ‘formidable’ farmers, officials sometimes had to appeal to their emotions or employ monetary incentives rather than use unilateral compulsory measures. It was also the market language of production and consumption that persuaded farmers to understand why slate-roofing was a good thing and worth the investment of their labor and money for the ‘profitable’ project. Governmental institutions and agricultural economists produced a range of reports on the economic effect of the roof improvement in the rural villages.34, According to an economist’s evaluation on the rate of earnings in 1976, roof improvement would generate profit in the end.35 Under the assumption that a thatched roof needed to be replaced every year or other year, the economist calculated that the cost of roofing materials would be compensated for largely through the future labor saved from the annual re-roofing. To explain rapid ways to make up for the expenditure (consumption) on the relatively expensive manufactured slate, the focus of the analysis soon shifted to more productive allocation of labor power especially to the activities of agricultural production such as cultivation, the rearing of livestock, the production of straw goods, improving the soil, and public works. Farmers had been accustomed to roofing their thatched houses with new grass after the busy harvest period. This previously ‘uncounted’ off-season labor began to be captured now as a value-added resource to be exchanged, especially with manufactured goods like slate in the market. At this juncture, the discourse of agricultural production surrounding rural roofs located its meaning in the system of exchange between manufactured goods and agricultural labor.

Exchange on the Roof: Roofing with Debts and Slate Chaebŏls

1) Roofing with Debts

The roof improvement project was ‘officially’ completed in 1978. In a span of seven to eight years, 2,618,000 thatched houses had their old roofs replaced mainly with slate or tile.36, In 1979, one government publication on the campaign asserted that the roof improvement project “cast off the old skin of rural village,” “developed the spirit of self-help and enterprise among farmers,” and “contributed to the rural economy.”37, The Saemaŭl roof improvement project was now being propagandized as a monumental symbol of rural development. However, the colorful roofs were a visual illusion of development achieved through the imposition of considerable financial and labor burdens on the farmers.

For most farm households, the roofing was obviously a burdensome task that required individual farmers to endure financial hardships in addition to administrative pressures. The government had unclear guidelines stating that those farm households who could afford to improve roofs for themselves should cover all the expenses, and the others would be subsidized for partial cost of building materials.39, Only a small number of farm households were capable of putting necessary materials and labor in roofing and most farmers could not finish the work without external loans or assistance. In the case of Wŏnsŏng County, when considerable number of farm households completed roof improvement in 1971, only 10% of them were able to pay all the expenses from their own pockets and the other houses had to rely on high interest loans.40

The government’s subsidy and loans were often not enough, and farmers had to make up for the lack with their own meager savings or other sources of loans and income. According to a report that analyzed the real cost of roofing in Sin’an County as of 1972, the expense of changing thatched roof into slates on a three-room house (82.6–99.2m2) totaled about 59,300 wŏn, and each farm household had to spend approximately 35,000 to 45,000 wŏn from their savings or other sources of funds immediately.41, Specifically, the total expense included roughly 90 pieces of slates per house (33,300 wŏn in discount price for group), timber (8,000 wŏn), roof ridges (15,000 wŏn), and wages for two technical experts (3,000 wŏn). Necessary cement and farmers’ own labor were not counted in the total sum. The farmers were allowed to get a loan of 10,000 wŏn with a governmental subsidy of 5,000 wŏn or take out a loan of 20,000 wŏn without a subsidy. The government support accounted for less than 10 percent of the total expense on average. Based on a simple calculation that considers the roofing expenses in terms of the farmers’ most available commodity, the entire cost farmers had to shoulder immediately was almost equal to ten bags of unhulled rice at a price of 4,000 wŏn per bag.42, It was also about 10 percent of the gross annual income per farm household (429,000 wŏn) as of 1972.43, Considering that the expenses for agricultural management – seeds, fertilizers, agrichemicals, machines and implements, feedstuffs, rent, wages, costs of upkeep, and the like – totaled 75,000 wŏn per farm household on average in 1972,44, the roof improvement, whose immediate cost was equivalent to more than half of the yearly farm management expenditure, was not a trivial household chore especially for destitute farmers. Sympathizing with the farmers’ difficulties, a 1972 article in the Tonga ilbo wrote, “Weak pillars cause worries if they could support a new slated roof, but debts give more anxiety.”45

2) Slate Chaebŏls

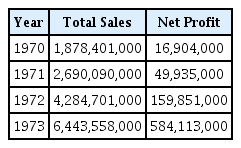

In contrast to the farmers’ financial difficulties, the slate industry grew drastically in the 1970s. Large slate manufacturers such as Han’guk (current Pyŏksan Group), Kŭmgang (current KCC Group), Ssangyong, Tongyang, Cheil, Taehan, and Koryŏ all enjoyed rapid capital accumulation through the roof improvement project in the countryside.46, As the roofing in the rural villages was almost completed in 1978, the slate industry went into decline.47, Yet by this time, companies such as Han’guk and Kŭmgang had already finished solidifying the early foundation for their current structure as large conglomerates (Pyŏksan and KCC Group Chaebŏls).48

Han’guk Slate Industrial Company started its business in 1962 when the company’s founder Kim In-dŭk, one of the largest theater owners in the 1950s, took over a slate factory in Seoul.49, The slate factory was originally run by Asano (淺野) Cement Company during the colonial period and was later vested to the South Korean government after liberation.50, Kim In-dŭk’s Han’guk Slate experienced swift business growth with the boom of slate-roofing in the countryside in the early 1970s. In Kim’s “My Notes of Company Management” in 1974, he wrote: “By the launch of the New Village Movement, the usefulness of slate has been verified. This has brought about today’s formation of Han’guk Slate Group, which centers on Han’guk Sŭlleit’ŭ (slate manufacturing in Seoul) as my company group’s parent body and consisted of the other affiliates such as Han’guk Kŏnŏp (construction industry), Tongyang Mulsan (Western tableware manufacturing), Kŭktong P’ilt’ŏ (filter manufacturing), Han’guk Yunibaek (electronic calculators), Tongyang Hŭnghaeng (theater), Taeyŏng Hŭnghaeng (theater), and Cheil Sŭlleit’ŭ (slate manufacturing in Pusan).”51, Business magazines and newspapers paid much attention to the company’s success in their analytical sections for the listed corporations. Hyŏndae kyŏngje (Contemporary Economy) reported that the sales of Han’guk Slate in 1972 marked an increase of 291.7% compared with the previous year52,; Sanŏp kyŏngje (Industrial Economy) wrote that Han’guk Slate had 60% domestic market share and its “enviable business boom” would continue with the springboard of the New Village projects and evaluated that Han’guk Slate had just joined the ranks of Chaebŏl.53

Predicting that the rural roofing would be completed soon, Han’guk Slate Group began to prepare for the post-roofing market. In an interview with Sŏul kyŏngje (Seoul Economy) in 1974, Kim In-dŭk stressed: “The Roof Improvement Project is still an important assignment, but the fundamental structure of houses should be reconstructed from now on in terms of resource saving.”54, At the time of the interview, the company was already investing in the diversified production of construction materials, expanding its business areas to more comprehensive industry of construction.55, Sŏul kyŏngje (Seoul Economy) commented on such a tactical shift of business, writing: “He [Kim In-dŭk] cannot experience business recession because he himself creates market demand as well as national profits.”56, Affirming this observation, Han’guk Slate Group (current Pyŏksan Group Chaebŏl) continued to grow until the South Korean IMF currency crisis in the late 1990s, increasing its affiliates up to 17.57

Kŭmgang Slate Industrial Company was established in 1958 by Chŏng Sang-yŏng, the youngest brother of the Hyundai Group Chaebŏl’s founder Chŏng Chu-yŏng.59, The slate company was in dire financial straits until the late 1960s due to costs involved in the construction of a new factory.60, It was the government’s roof improvement projects that saved the company from these financial difficulties. As explained in one of the company’s official publications, “As the Saemaŭl roof improvement project expanded to all over the country after the early 1970s, demand for slate showed an explosive increase. ... This period was the most prospering days of Kŭmgang Slate since its establishment.”61, Kŭmgang Slate’s business growth was outstanding especially from the mid-1970s; however, the company’s financial status began to improve already in the early 1970s; from 1970 to 1973, the company’s sales of slate showed an annual average growth of over 50%.62

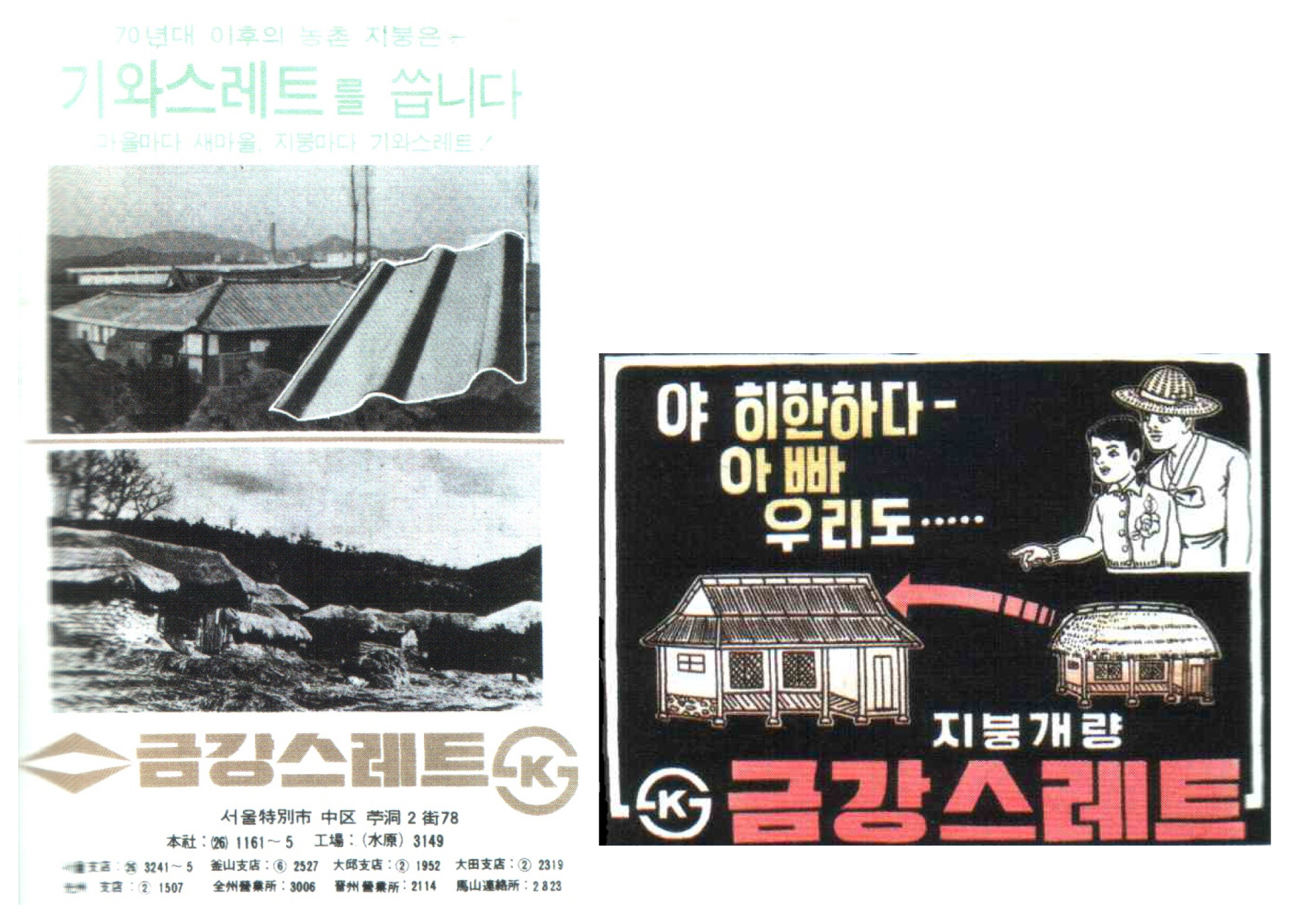

Kŭmgang Slate’s marketing strategy toward farmers had to be a little more aggressive given that Han’guk Slate occupied 60% of the slate market share. Targeting farmers more directly, Kŭmgang Slates advertised its products extensively in the countryside with a slogan saying, “Rural roofs in the 1970s use slate.” (Figure 4, left) The product advertisements always displayed before and after illustrations of roofing. (Figure 4, right) As a means of advertising Kŭmgang Slate’s products more efficiently, the company also made a promotional film for the government’s roof improvement project with the support of the Ministry of Home Affairs.63, (Figure 5) The 15-minute-long film showed the procedure of slate-roofing step by step. The government assisted in distributing the film to 275 local cities and counties all over the country so that farmers could watch it in local village halls. When the company name ‘Kŭmgang’ clearly appeared in the government-sponsored New Village campaign movie, farmers accepted Kŭmgang’s slate as an officially accredited product. In relation to the government’s cooperation during this period, Kŭmgang Slate’s company history wrote, “The central government regularly investigated the progress of the Saemaŭl roof improvement project by the instruction of the President. Local government offices urged the owners of farmhouses in their areas of responsibility to improve the thatched roofs. Mayors and county governors threw themselves into the task of securing the sufficient quantity of slate with enthusiasm. The purchase orders of local offices were always rushed to slate manufacturers at the same time.”64

In the same way that the Han’guk Slate Group shifted its corporate strategy in the mid-1970s, Kŭmgang Slate Industrial Company (current KCC Group Chaebŏl) also made an effort to diversify their products and expanded into more comprehensive construction industry around the same time.65, In the mid-1980s, the company became a representative corporate group that produced a wide variety of construction materials in South Korea. There was no doubt that the slate-based capital of the 1970s enabled such a swift growth and increase of affiliates. According to a government press release on domestic corporate groups subject to limitations on cross-shareholdings in 2014, KCC Group Chaebŏl was ranked 33rd in the size of total assets in the private sector, while Samsung Group was ranked first and Hyundai Motors Group second.66

On the other side of these large slate makers, local retailers and construction technicians also accumulated considerable wealth, producing a phenomenon that could be called ‘rural legends.’

A Mr. Kim opened a retail store for a slate manufacturing company in Masan City at the very beginning of the roof improvement project, and in roughly six years he was able to set up his own construction company.68, A Mr. Ko, who was “unskilled ‘C level’ carpenter,” became the second wealthiest person in his village seven years after he started to specialize in slate construction.69, In another instance, an extremely poor farmer by the name of Chang Chŏng-sik went to a city to learn slate-roofing, and earned enough money to buy three majigi (patch) of his own rice paddy in only three years.70, In 1978, a newspaper called both of the manufacturing companies and the successful individuals “slate Chaebŏls,” the former literally and the latter figuratively.71

Conclusion

1) Developmentalist Aesthetics of the Roof

The Saemaŭl Roof Improvement Project was firmly based upon the contrasting representation or symbolism that distinguished ‘underdeveloped’ rural space and ‘flourishing’ urban space. This image strategy played the role of concealing the unequal and constant exchange relationship between agriculture and manufacture. Simultaneously, however, as seen from the process of how the extracted capital flowed into slate industry through the reconstruction of farmers’ roofs, such a clear-cut image of unevenness functioned to maintain and reinforce the inequitable exchanges between the countryside and the city in the market. In this capitalist mechanism of image strategy, the agricultural sector continued to provide fundamental resources for augmenting the manufacture industries throughout the post-war industrialization.

The ideology of development and modernization was deeply rooted in every phase of this mechanism: from the production of contrasting spatial discourses to the reproduction of unequal exchange. The new roofs were a concrete and microscopic product of this constant renewal of unevenness, but at the same time they became an efficient and equally powerful means for bolstering the very hegemonic capitalist ideology, particularly through color. Slated or tiled roofs, painted in different primary colors, presented a striking visualization of a changing countryside vis-à-vis the monochromatic landscape of faded straw. In particular, villages near highways and principal roads were reconfigured into ‘canvases’ on which the rapid development of rural area would be painted in yellow, blue, and red.

The initial investment and administrative guidance in roof improvement deliberately focused on rural villages located along highways, main roads, railroads, and scenic spots where the roofs were most prominently displayed and viewed.72, At first, the capped slates or tiles were randomly painted in lurid colors. However, these primary hues led to the issue of discordant color combinations. For instance, a mountain village in Ch’ŏngyang county became known as “bier village (Sangyŏ maŭl)” because the painted roofs were said to resemble the colorfully decorated traditional biers on which a coffin is placed.73, The central government started to disseminate instruction manuals on how to attain harmonious colors for roofs and walls by offering limited shades and combinations.74, (Figure 6) County offices also gradually tightened control over chromatic choices in each village.75 With such a dense and microscopic power dictating even the color shade of a farmer’s roof, the systematic and equally stentorian ethos of developmentalism and modernization was seen and heard all across the quotidian spaces of the countryside.

The developmentalist propagation culminated in the discourse on the ‘preservation of thatched houses.’ In 1978, the final planned year of the roof improvement project, the Ministry of Home Affairs mandated local government offices to seek out thatched roof houses and villages worth preserving and to designate them as protected sites or districts.77, This order was based on the anticipation that thatched roof houses would soon disappear from South Korea completely. This ‘concern’ was expressed through the expression of nationalist affection for thatched roof houses in the rural villages; the disappearing straw roof was now described as an emblem of, “the spirit and emotion of our ancestors,” “the unique flavor and fragrance of our nation,” and “the precious cultural legacy of long history.”78, The government’s announcement was, however, rather closer to a kind of paradoxical proclamation of proudly boasting ‘a complete escape from poverty.’ Even though the thatched roof house was imbued with metaphysical rhetoric of nostalgia, it continued to be seen as “the symbol of rural poverty.”79, As such, the thatched roof houses had to be preserved as “historical material”80, that could serve as a reminder of ‘past poverty,’ as well as traditional culture once the “shadow of thatched houses vanishes away even in children’s magazines.”81

Shortly after the central government’s announcement, each of the provincial government offices made their own detailed plans for “the revival of thatched roof house” by sending local officials to search for candidate villages.82, An owner of a thatched roof house was amazed to discover that his house was introduced on TV as a part of the building preservation program.83, After his initial amazement wore off, the house owner bemoaned that only two years prior he had to make an appeal to avoid mandatory roof improvement. Smiling bitterly, he quoted an old Korean saying, “Give the disease and offer the remedy.” Yet, most people were “astonished at how much things had changed (隔世之感, Kyŏksejigam).”84 The illusive image of ‘development’ spread widely at such a moment, when people recognize the ‘absence’ of the old thatched roofs through the public discourse of preservation, and they communicated diverse sentiments toward the ‘astonishing change’ that suddenly seemed to require an organized protection of thatched roofs.

What the discourse of preservation immured in museum-like spaces was, however, an image of poverty, not the poverty itself. The improvement project of thatched roofs was grounded in spatio-visual representation that highlighted unbridgeable disparity between the countryside covered with thatched roofs and the concrete high rises of the city. There was little consideration for the constant unequal circulation of products and surplus values behind this relative poverty and wealth. In such an excessive emphasis on only ostensible difference, the slated roofs could be seen as a visual signifier of rural changes that eventually narrowed the spatial gap. Yet, in the process of covering roofs that were emblematic of rural destitution of farmers, the plight of their resources and effort, the more fundamental issue of rural poverty, which was located in the exchange relationship between agriculture and manufacturing, remained concealed and obscured.

2) Slate Roof Monster

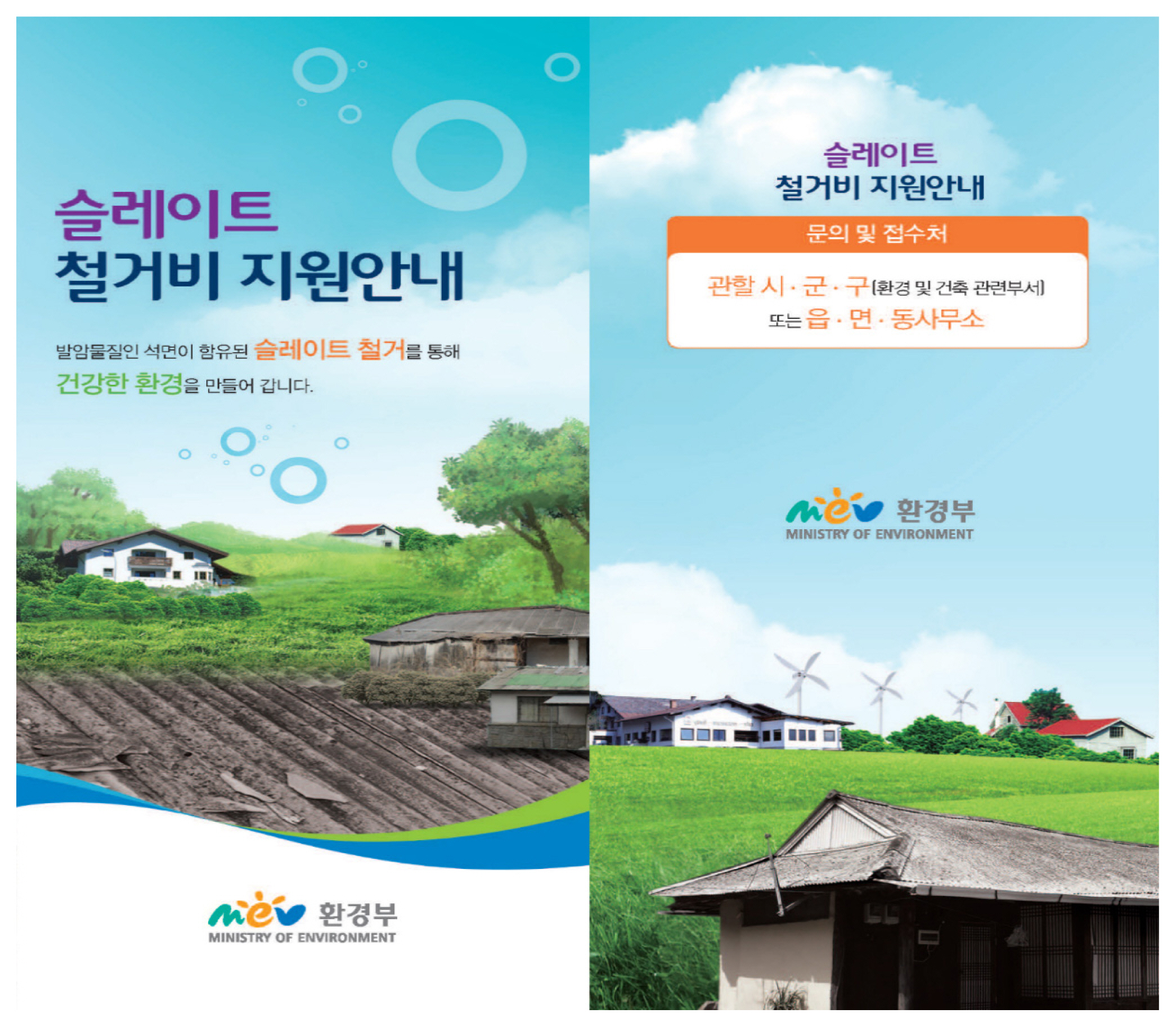

Before long, however, people began to raise doubts about the quality of slate roofs that served to mask this disparity. Slate contained a ratio of roughly 10 to 15% asbestos, a class one carcinogen.85, In South Korea, the toxicity of asbestos slate began to be widely known by the public in the 2000s, and since 2011, the government began to subsidize the demolition of slate roofs.86, Almost four decades after the nationwide launch of the slate-roofing project, the Saemaŭl slate roofs have become a source of danger, one that threatens public health, as well as social capital.87, In 2010, a newspaper article remarked that “the symbol of the New Village Movement is under demolition.”88, In another article from 2013, the iconic slate roof was likened to a “monster (koemul).”89, The designation of “monster” was not merely a metaphor, especially when one considers the demolition workers having to wear respirators and other protective gear to shield themselves from the toxic asbestos dust. (Figure 7)

In 2014, the Ministry of Environment printed a leaflet to provide information on its subsidy program for the removal of slate roofs.91, The leaflet included the contrasting images of unhealthy slate roofs in grey and healthy new houses in green. (Figure 8) On the other side of the government’s campaign, many people criticized the meager size of the subsidy and the slow progress of the removal program; and some of them urged the central government to take more aggressive measures, insisting that the removal of slate roofs in the rural areas should be connected to a “green growth project”92, or “the second New Village Movement.”93 Ironically, the methods used to represent living spaces and the intertwining of these projects with discourses of economic growth in the present mirrored those employed during the 1970s to promote slate roofing in the countryside.

Notes

As for historical research on the Rural New Village Movement, refer to the following publications. Kim Yŏng-mi, Kŭdŭl ŭi Saemaŭl Undong [Their New Village Movement] (Seoul: P’urŭn yŏksa, 2009); Yi Hwan-byŏng, Nongch’on Saemaŭl Undong: Sinhwa wa yŏksa sai esŏ [The Rural New Village Movement: Between Myth and History] (Seoul: Sŏn’in, 2017); Hŏ Ŭn, Naengjŏn kwa Saemaŭl [The Cold War and the New Village] (Seoul: Ch’angbi, 2022); Kim Sungjo, “1970-nyŏndae nongch’on chut’aek kaeryang saŏp ŭi chŏn’gae: Chŏngbu, nongmin, chabon ŭi kwan’gyae rŭl chungsim ŭro [The dynamics among the state, farmers, and manufacturing capital in the rural housing improvement project in 1970s South Korea],” Yŏksa wa Silhak 64 (November 2017); Kim Sungjo, “1970-nyŏndae nongch’on chugŏ kong’gan ŭi pyŏnhwa wa sobija nongmin: Int’eriŏ kong’gan kwa t’ellebijŏn sobi rŭl chungsim ŭro [Televisions and the new interior space: The transformation of rural housing and farmers as consumers],” Han’guksa Yŏn’gu 184 (March 2019); Kim Sungjo, “Urbanizing the Countryside: The Developmentalist Designs of the New Village and Farmhouse in 1970s Rural Korea,” International Journal of Korean History 25, no. 1 (February 2020).

Naemubu [Ministry of Home Affairs], Saemaŭl Undong 10-nyŏnsa [A 10 Year History of the New Village Movement] (Seoul: Naemubu, 1980), 484–485.

Kwŏn Yŏng-min, “Ilche singminji sidae ŭi nongmin undong kwa nongmin munhangnon [A Study on the Movement of Peasantry Literature under the Japanese Rule],” Chindanhakbo 62 (December 1986); Yi Kyŏng-jae, “Yi Ki-yŏng sosŏl e nat’anan Manju lok’ŏllit’i [A Study on the Locality of Lee Ki-yŏng’s Novels],” Han’guk kŭndae munhak yŏn’gu 25 (April 2012); Watanabe Naoki, “Singminji Chosŏn ŭi p’ŭrollet’aria nongmin munhak kwa ‘Manju’: ‘Hyŏphwa’ ŭi sŏsa wa ‘chaebalmyŏngdoen nongbonjuŭi’ [‘Manchuria’ and the Agrarian Proletariat Literature of Colonial Korea: Narratives of ‘Cooperation (Kyōwa)’ and ‘Reinventing Agrarianism’],” Han’guk munhak yŏn’gu 33 (December 2007).

Raymond Williams, The Country and the City (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973).

Yi Tae-gŭn, Han’guk chŏnjaeng kwa 1950-nyŏndae chabon ch’ukchŏk [The Korean War and Capital Accumulation in the 1950s] (Seoul: Kkach’i, 1987); Hong Sŏng-yu, “Han’guk kyŏngje ŭi chabon ch’ukchŏk kwajŏng kwa chaejŏng kŭmyung chŏngch’aek, 1953–1963 [Capital Accumulation Process and Financial Policy in Korean Economy, 1953–1963],” Kyŏngje nonjip 3, no. 3 (September 1964).

These topics are deeply involved with different attempts to explain the cause of the so-called late industrializer’s successful catch-up, as in Alice H. Amsden, Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989); Jung-en Woo, Race to the Swift: State and Finance in Korean Industrialization (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991); Robert Wade, Governing the Market: Economic Theory and the Role of Government in East Asian Industrialization (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990); and Peter B. Evans, Embedded Autonomy: States and Industrial Transformation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995). Sometimes, these topics are also connected to polemic debates over the historical origin of such a rapid ‘capitalist development,’ as in Atul Kohli, Stephan Haggard, David Kang, and Chung-In Moon’s debates in World Development (1994 & 1997); and Carter Eckert, Offspring of Empire: The Koch’ang Kims and the Colonial Origins of Korean Capitalism, 1876–1945 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991).

James C. Scott, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985).

For representative examples, see Naemubu, Saemaŭl Undong 10-nyŏnsa; Naemubu [Ministry of Home Affairs], Saemaŭl Undong – Sijak esŏ onŭl kkaji [The New Village Movement – from Beginning to Today] (Seoul: Naemubu, 1973–1979); Park Jin Hwan, Park Chung Hee taet’ongnyŏng ŭi Han’guk kyŏngje kŭndaehwa wa Saemaŭl Undong [Modernization of the Korea’s Traditional Economy and the New Village Movement under the Leadership of Late President Park Chung Hee] (Seoul: Park Chung Hee taet’ongnyŏng kinyŏm saŏphoe, 2005).

For an example, see Pak Chin-do and Han Do-hyŏn, “Saemaŭl Undong kwa Yusin ch’eje – Park Chung Hee chŏnggwŏn ŭi nongch’on Saemaŭl Undong ŭl chungsim ŭro [The New Village Movement and the Yusin System – Centering on the Rural New Village Movement of the Park Chung Hee Regime],” Yŏksa pip’yŏng 47 (Summer 1999).

Amsden, Asia’s Next Giant; Hyung-A Kim, Korea’s Development under Park Chung Hee: Rapid Industrialization, 1961–79 (London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004); Yi Yŏng-hun, “20-segi Han’guk kyŏngjesa, sasangsa wa Park Chung Hee [The Economic and Intellectual History of 20th Century Korea and Park Chung Hee]” in Park Chung Hee sidae wa Han’guk hyŏndaesa [The Park Chung Hee Era and the Contemporary History of Korea], ed. Chŏng Sŏng-hwa (Seoul: Sŏn’in, 2006).

Han’guk nongch’on munhwa yŏn’guhoe [The Korean Rural Culture Research Society], Nongmin munhwa [Peasant Culture] 19 (March 1971), 25.

Image from Han’guk nongch’on munhwa yŏn’guhoe, Nongmin munhwa 19, 25.

Naemubu chibang haengjŏngguk nongch’on chut’aek kaeryangkwa [Division of Rural Housing Improvement at the Ministry of Home Affairs], Minjok ŭi taeyŏksa: Nongch’on chut’aeksa [The Great Construction Project of the Nation: The History of Rural Housing] (Seoul: Naemubu, 1979), 57.

“Sangjang kiŏp chindan [Analysis of listed corporations],” Hyŏndae kyŏngje, May 26, 1973.

Naemubu chibang haengjŏngguk nongch’on chut’aek kaeryangkwa, Minjok ŭi taeyŏksa: Nongch’on chut’aeksa, 58.

Naemubu, Saemaŭl Undong 10-nyŏnsa, 484.

Naemubu [Ministry of Home Affairs], Saemaŭl Undong kilchabi [A Guide to the New Village Movement] (Seoul: Naemubu, 1975), 376.

Naemubu, Saemaŭl Undong kilchabi, 375.

Image from Naemubu chibang haengjŏngguk nongch’on chut’aek kaeryangkwa, Minjok ŭi taeyŏksa: Nongch’on chut’aeksa, 45.

Image from Naemubu chibang haengjŏngguk nongch’on chut’aek kaeryangkwa, Minjok ŭi taeyŏksa: Nongch’on chut’aeksa, 612.

“Saemaŭl ŭl kada (3): Apsŏn maŭl, twijin maŭl [At the sites of New Village Movement (3): Advanced village, lagged village],” Tonga ilbo, April 11, 1972.

“Saemaŭl ŭl kada (3).”

“Myŏnjang 3-myŏng tto p’amyŏn, Kyŏnggi Kangwŏn sŏ Saemaŭl pujin [Three township chiefs dismissed again, due to inactivity of New Village Movement in Kyŏnggi and Kangwŏn Provinces],” Tonga ilbo, March 20, 1972; “Saemaŭl chido hadŏn myŏnjang sunjik [Township chief dies at his post while carrying out New Village Movement],” Kyŏnghyang sinmun, March 22, 1972; “Tagasŏn chajo ŭi kyŏlsil, Saemaŭl saŏp kubo [Fruit of self-help approaches; New Village Movement goes at a run],” Kyŏnghyang sinmun, April 5, 1972; “Pul ŭn putŏtchiman…, ‘Saemaŭl ŭl kada’ sirijŭ rŭl mach’igo, ch’wijae kija chwadamhoe [Even if New Village Movement ignited …, Reporters’ discussion meeting following the serial reports, ‘At the sites of New Village Movement’],” Tonga ilbo, April 14, 1972; “Saemaŭl ch’ŏngso ch’amga tongsŏgi kwaro sunjik [Official dies from overwork while participating in New Village cleaning project],” Kyŏnghyang sinmun, February 2, 1977; “Chibang kongmuwŏn aehwan kwa yŏngyok ŭi hŏsil (8): Pugunsu [Local officials’ joys, sorrows, honors, and disgraces (8): Deputy county governors],” Tonga ilbo, September 9, 1977; “Chibang kongmuwŏn aehwan kwa yŏngyok ŭi hŏsil (14): Saemaŭl chidoja [Local officials’ joys, sorrows, honors, and disgraces (14): New village leaders],” Tonga ilbo, September 23, 1977.

“Sasŏl: Ilsŏn haengjŏng ŭi kibon chase – Ch’oga chibung kangje ch’ŏlgŏ choch’ŏ rŭl kaet’an hamyŏnsŏ [Editorial: Basic attitude of public administration – We deplore the forcible demolition of thatched houses],” Chosŏn ilbo, May 10, 1974.

“Ch’ŏngju int’ŏch’einji pugŭn ch’oga 11-tong kangje ro ch’ŏlgŏ [Ch’ŏngwŏn County office demolishes 11 thatched houses near Ch’ŏngju interchange by force],” Tonga ilbo, June 13, 1972.

“Nongch’on sae p’ungsokto (146): Chugŏ pyŏnhyŏk (5), Mujigae chibung (ha) [New trend in the countryside (146): Housing revolution (5), Rainbow roof (2)],” Kyŏnghyang sinmun, May 15, 1978.

“Nongch’on sae p’ungsokto (146).”

“Ch’oga chibung wi e inŭn kiwa chibung [Tiled roof overlaying a thatched roof],” Tonga ilbo, July 2, 1970.

“Nop’ŭn saram onda, Pyŏrakch’igi nongga kaeryang [Big shots coming, Hurried construction of farmhouses],” Tonga ilbo, June 3, 1978.

“Nongch’on sae p’ungsokto (144): Chugŏ pyŏnhyŏk (3), Ch’oga chibung aehwan [New trend in the countryside (144): Housing revolution (3), Joys and sorrows of thatched roof],” Kyŏnghyang sinmun, May 11, 1978.

“Nongch’on sae p’ungsokto (146).”

“Nongch’on sae p’ungsokto (146).”

“Nongch’on sae p’ungsokto (147): Chugŏ pyŏnhyŏk (6), P’eint’ŭch’il [New trend in the countryside (147): Housing revolution (6), Painting],” Kyŏnghyang sinmun, May 18, 1978.

Naemubu, Saemaŭl Undong kilchabi, 343–345.

Pan Sŏng-hwan, “Chibung kaeryang ŭi kyŏngjejŏk hyokwa punsŏk [An Economic Analysis of Roof-Improvement Project in Korea],” Nongŏp kyŏngje yŏn’gu [Korean Journal of Agricultural Economics] 18, no. 1 (July 1976).

Naemubu, Saemaŭl Undong 10-nyŏnsa, 484–485.

Naemubu chibang haengjŏngguk nongch’on chut’aek kaeryangkwa, Minjok ŭi taeyŏksa: Nongch’on chut’aeksa, 150.

Source from Naemubu, Saemaŭl Undong 10-nyŏnsa, 484.

Naemubu, Saemaŭl Undong kilchabi, 346–347.

“Saemaŭl ŭl kada (4): Chipko nŏmgyŏya hal saryedŭl [At the sites of New Village Movement (4): Some cases we need to address],” Tonga ilbo, April 12, 1972.

“Saemaŭl ŭl kada (4).”

“Saemaŭl ŭl kada (4).”

T’onggyech’ŏng [Statistics Korea], T’onggye ro pon Han’guk ŭi palchach’wi [Tracing Korea through Statistics] (Seoul: T’onggyech’ŏng, 1995), 95; Nongsusanbu [Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries], Nongnimsusan t’onggye yŏnbo [Statistical Yearbook of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries] (Seoul: Nongsusanbu, each year).

T’onggyech’ŏng, T’onggye ro pon Han’guk ŭi palchach’wi, 99; Nongsusanbu, Nongnimsusan t’onggye yŏnbo.

“(Sajin) Ch’oga chibung ŭl sŭlleit’ŭ ro pakkunŭn chagŏp e yŏl ŭl ollinŭn ŏnŭ Saemaŭl chagŏpchang [(Photograph) A construction site for the New Village Movement where villagers are fervently replacing thatched roofs with slates],” Tonga ilbo, April 12, 1972.

“Han’guk Sŭllet’ŭ, sŭllet’ŭ taeil such’ul pon’gyŏkhwa [Han’guk Slate Company’s full-scale exporting of slates to Japan],” Maeil kyŏngje, August 4, 1973; “Sŭlleit’ŭ ŏpkye p’anmaejŏn yesang [Sales war to break out in slate business circle],” Kyŏnghyang sinmun, June 13, 1974; “Sŭlleit’ŭ ŏpkye samp’ajŏn yesang [Three-cornered sales war to start in slate business circle],” Maeil kyŏngje, December 5, 1974.

“Sŭlleit’ŭ ŏpkye kadongryul chŏha [Slate industry circle marks a decline in operation rate],” Maeil kyŏngje, June 17, 1978.

“Kŭmgang Sŭlleit’ŭ [Kŭmgang Slate Industries Ltd.],” Maeil kyŏngje, July 19, 1973; “Kyŏlsan punsŏk Pyŏksan Kŭrup [Financial analysis of Pyŏksan Group],” Maeil kyŏngje, March 11, 1977; “Kŭmgang [Kŭmgang],” Maeil kyŏngje, March 10, 1978.

Pyŏksan Kim In-dŭk sŏnsaeng hoegap kinyŏm munjip palgan wiwŏnhoe [Publication Committee for Essay Collection in Honor of Pyŏksan Kim In-dŭk’s 60th Birthday], Pyŏksan Kim In-dŭk sŏnsaeng hoegap kinyŏm: Nam poda apsŏnŭn saram i toerira [Essay Collection in Honor of Pyŏksan Kim In-dŭk’s 60th Birthday: Take the Initiative] (Seoul: Pyŏksan Kim In-dŭk sŏnsaeng hoegap kinyŏm munjip palgan piwŏnhoe, 1975), 133–134.

Pyŏksan Kim In-dŭk sŏnsaeng hoegap kinyŏm munjip palgan wiwŏnhoe, Pyŏksan Kim In-dŭk sŏnsaeng hoegap kinyŏm: Nam poda apsŏnŭn saram i toerira, 134.

Kim In-dŭk, “Na ŭi kiŏp kyŏngyŏnggi [My Notes of Company Management],” Han’guk kidok sirŏbin hoebo [Bulletin of Christian Businessmen’s Committee Korea] (Seoul: CBMC Korea, January 31, 1974).

“Sangjang kiŏp chindan.”

“Sangjang kiŏp kyŏngyŏng chŏllyak [Management strategies of listed corporations],” Sanŏp kyŏngje, July 1, 1973.

“Kyŏngjein int’ŏbyu: Kim In-dŭk [Interview with businessmen: Kim In-dŭk],” Sŏul kyŏngje, July 2, 1974.

“Han’guk ŭi pijinisŭ kŭrup: Han’guk Sŭlet’ŭ Kŭrup p’yŏn [Korea’s business groups: Han’guk Slate Group],” Kyŏngyŏng sinmun, March 15, 1974.

“Kyŏngjein int’ŏbyu: Kim In-dŭk.”

“Pyŏksan, Pyŏksan Kŏnsŏl p’asan pulttong t’wilkka kkŭngkkŭng [Pyŏksan Group fears the aftereffects of Pyŏksan Construction’s bankruptcy],” Asia kyŏngje, April 3, 2014.

Image from KCC 50-nyŏnsa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏnhoe, KCC 50-nyŏnsa, 147 and 160.

KCC 50-nyŏnsa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏnhoe [Compilation Committee for Fifty Years of KCC Corporation], KCC 50-nyŏnsa [Fifty Years of KCC Corporation] (Seoul: KCC, 2009), 118.

KCC 50-nyŏnsa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏnhoe, KCC 50-nyŏnsa, 146.

KCC 50-nyŏnsa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏnhoe, KCC 50-nyŏnsa, 157.

KCC 50-nyŏnsa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏnhoe, KCC 50-nyŏnsa, 158.

KCC 50-nyŏnsa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏnhoe, KCC 50-nyŏnsa, 157.

KCC 50-nyŏnsa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏnhoe, KCC 50-nyŏnsa, 164.

Kongjŏng kŏrae wiwŏnhoe [Fair Trade Commission], “Podo charyo: Sangho ch’ulcha chehan kiŏp chiptan [Press Release: Corporate Groups Subject to Limitations on Cross-shareholding]” (Sejong-si: Kongjŏng kŏrae wiwŏnhoe, April 1, 2014).

Image from KCC 50-nyŏnsa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏnhoe, KCC 50-nyŏnsa, 159.

As the slate sales boomed, retailers competed with each other. At last, retail stores did not just stay in the nearby town areas but moved into around the rural villages to get orders. (“Nongch’on sae p’ungsokto (150): Chugŏ pyŏnhyŏk (9), Sŭlleit’ŭ chaebŏl [New trend in the countryside (150): Housing revolution (9), Slate Chaebŏl conglomerates],” Kyŏnghyang sinmun, May 27, 1978)

“Nongch’on sae p’ungsokto (150).”

“Nongch’on sae p’ungsokto (150).”

“Nongch’on sae p’ungsokto (150).”

Naemubu, Saemaŭl Undong kilchabi, 346; “Kyŏngbu kosok ch’ŏlli (3): Taegu-Pusan kan [Seoul-Pusan Highway, a thousand ri (3): Section between Taegu and Pusan],” Tonga ilbo, July 2, 1970; “Kansŏn toro pyŏn ch’oga chibung kaeryang e si, 2 man wŏn ssik yungja [Seoul city lends 20 thousand wŏn to roofing of thatched house near main roads],” Kyŏnghyang sinmun, February 10, 1971; “Kosokto pyŏn chipchung kaebal [Areas near highway to be developed intensively],” Kyŏnghyang sinmun, March 13, 1972; “Chido ka pakkwinda (2): Kyŏngbu Kosoktoro [Map changing (2): Seoul-Pusan Highway],” Maeil kyŏngje, August 16, 1973.

The villagers painted the flat sides of slated roofs in green and the edges in red. (“Nongch’on sae p’ungsokto (147)”)

Naemubu chibang haengjŏngguk nongch’on chut’aek kaeryangkwa, Minjok ŭi taeyŏksa: Nongch’on chut’aeksa, 372–374.

Naemubu chibang haengjŏngguk nongch’on chut’aek kaeryangkwa, Minjok ŭi taeyŏksa: Nongch’on chut’aeksa, 372–374.

Image from Naemubu chibang haengjŏngguk nongch’on chut’aek kaeryangkwa, Minjok ŭi taeyŏksa: Nongch’on chut’aeksa, 388.

Naemubu chibang haengjŏngguk nongch’on chut’aek kaeryangkwa, Minjok ŭi taeyŏksa: Nongch’on chut’aeksa, 373–374.

Naemubu chibang haengjŏngguk nongch’on chut’aek kaeryangkwa, Minjok ŭi taeyŏksa: Nongch’on chut’aeksa, 373–374.

Naemubu chibang haengjŏngguk nongch’on chut’aek kaeryangkwa, Minjok ŭi taeyŏksa: Nongch’on chut’aeksa, 373.

Naemubu chibang haengjŏngguk nongch’on chut’aek kaeryangkwa, Minjok ŭi taeyŏksa: Nongch’on chut’aeksa, 373.

“Ch’oga ŭi pojon [Preservation of thatched house],” Sŏul sinmun, September 26, 1978.

“Nongch’on sae p’ungsokto (156): Chugŏ pyŏnhyŏk (15), Yetmosŭp pojon [New trend in the countryside (156): Housing revolution (15), Preservation of old thatched houses],” Kyŏnghyang sinmun, June 7, 1978.

“Pyŏng chugo yak chugo [Give the disease and offer the remedy],” Tonga ilbo, June 8, 1979.

“Ch’oga pojon [Preservation of thatched house],” Chungang ilbo, September 26, 1978.

Hwan’gyŏngbu [Ministry of Environment], “Sŭlleit’ŭ ch’ŏllgŏ chiwŏn saŏp hongbo rip’ŭllit [Information Leaflet: The Government Subsidy Project for the Removal of Slate Roofs]” (Sejong-si: Hwan’gyŏngbu, 2014).

“Sŏkmyŏn, ŏlmana wihŏmhan’ga… Changgi noch’ul ttaen aksŏng pongmagam yubal [Asbestos, how toxic is it… Long-term exposure causes peritoneal cancer],” Chosŏn ilbo, April 15, 2013; Hwan’gyŏngbu, “Sŭlleit’ŭ ch’ŏllgŏ chiwŏn saŏp hongbo rip’ŭllit.”

As for the history of asbestos in South Korea, refer to the following publication. Kang Yeonsil, “Transnational Hazard: A History of Asbestos in South Korea, 1938–1993,” Han’guk kwahaksa hakhoeji [The Korean Journal for the History of Science] 43, no. 2 (August 2021).

“Ch’ŏlgŏdoenŭn ‘Saemaŭl Undong sangjing’ [The symbol of the New Village Movement is under demolition],” Chosŏn ilbo, December 30, 2010.

“Saemaŭl Undong ŭi kŭnŭl: Koemul, sŭlleit’ŭ chibung ŭl ŏttŏtk’e [The shadow of the New Village Movement: How to deal with a monster, the slate roofs],” Kungmin ilbo, June 29, 2013.

Image from “Sunch’ang-gun, Chugŏ hwangyŏng kaesŏn saŏp 100-ŏk wŏn t’uip [Sunch’ang County invests 10 billion wŏn in the project of housing environment improvement],” Namwŏn Sunch’ang int’ŏnet nyusŭ, February 7, 2013.

According to a government’s survey in 2014, approximately 1,410,000 slate structures are still awaiting cleanup. (Hwan’gyŏngbu, “Sŭlleit’ŭ ch’ŏllgŏ chiwŏn saŏp hongbo rip’ŭllit.”)

“Aemultanji ro chŏllakhan sŭlleit’ŭ chibung [‘Slate roofs’ become a nuisance],” Naeil sinmun, January 9, 2009.

“Haru ppalli kŏdŏnaeya hal sŭlleit’ŭ chibung [‘Slate roofs’ need to be removed immediately],” Nongmin sinmun, May 25, 2009.

Image from Hwan’gyŏngbu, “Sŭlleit’ŭ ch’ŏllgŏ chiwŏn saŏp hongbo rip’ŭllit.”