조선 ‘페티코트’와 명나라의 ‘강남 스타일’

“Petticoat Fever” Driven by Chosŏn Korea Garments: Exploring a “fad” in Early Ming China and Its Implications for Regional Interactions between the Chosŏn and Ming Dynasties

Article information

Abstract

지금까지 한국학계에 알려지지 않았으나, 이 연구를 통해 조선 전기 제주에서 말총으로 만든 옷 마미군(馬尾裙)이 있었다는 것이 확인되었다. 조선의 마미군이 15세기 명나라 강남(江南) 지역에 전해졌고, 강남 지역 부유층 사이에서 크게 유행했다. 소위 “마미군 열풍”이었다. 조선의 마미군은 치마를 풍성하게 퍼지게 하여 고급스러워 보이는 효과가 있어, 명의 사대부들까지 폭넓게 마미군을 착용했다. 15세기 명의 강남 지역에서 화려한 의상으로 크게 유행하던 마미군 패션은 명 내 권력의 교체와 정책 방향으로 착용이 금지되며 급격히 소멸하는 운명을 맞이했다.

한편 이 논문은 중국국가박물관에 소장되어 있는 그림 『명헌종원소행락도(明憲宗元宵行樂圖)』를 상세히 분석했다. 그리고 이 그림이 지금까지 알려진 것처럼 북경에서 그려진 궁중화(宮中畵)가 아니라, 명 강남지역에서 그려진 그림이라는 점을 파악하여, 명 회화사(繪畫史) 연구의 오류를 바로잡았다는 점에서도 의의가 있다. 당시 화가는 성화제(成化帝)의 원소절 놀이 공간에 그가 상상할 수 있는 가장 화려하고 세련된 장식을 표현하기 위해 강남지역에서 유행했던 마미군 패션을 그려 넣었다. 『명헌종원소행락도』는 15세기 명 강남지역의 풍속과 패션 문화를 엿볼 수 있는 단서이다.

한중관계에 관한 많은 학문적 연구들은 15세기 조선과 명나라 사이의 문화와 교역이 조선의 서울과 명나라 북경의 사행을 통해서만 교류되었다고 주장하는 경향이 있다. 마미군은 조선의 제주도와 명의 강남지역을 연계할 수 있는 에피소드라는 점에서도 주목된다.

이 연구는 조선 시대 한중 교류 역사상을 보다 넓은 시각으로 바라볼 수 있게 하는 첫 단추가 될 것이다.

Trans Abstract

In the fifteenth century, Chosŏn Korean clothes were exported to the Jiangnan (江南) region in Ming China and became very popular among wealthy Chinese people. This was the so-called “Petticoat Fever”. This horsehair petticoat (Mamigun 馬尾裙) gave the wardrobe a fashionable silhouette by supporting and fully spreading the outer skirt. Literati wore them, too. Mamigun fashion, which once enjoyed great popularity in the Jiangnan area, disappeared after it was prohibited during the Ming period due to a change in power and a transition in policymaking.

On the other hand, this study is also significant in that it corrects errors in the study of art history in Ming Dynasty. This study analyzed in detail "Ming Emperor Xianzong's Tour of the Lantern Festival(明憲宗元宵行樂圖)" in the collection of the National Museum of China. I argued that the picture was not a royal court painting (宮中畵), drawned in Beijing, but a piece painted in the Jiangnan area of the Ming dynasty. The artist adopted the mamigun fashion widely enjoyed in the region at the moment in order to express the most splendid and glamourous adornments one could imagine in the place of entertainment for the emperor during the Lantern Festival. "Ming Emperor Xianzong's Tour of the Lantern Festiva" is a clue to the customs and fashion culture of the Jiangnan area of Ming Dynasty in the 15th century.

Many works of scholarship in Korea-China relations have tended to argue that culture and trade between Chosŏn and Ming Dynasties in the 15th century were exchanged only through envoys between Seoul of Chosŏn and Beijing of Ming. Mamigun is an interesting topic that gives us insight into the cultural exchange between the Chosŏn and Ming and can also be described as an episode that involves Cheju Island of Chosŏn and Jiangnan region of Ming, both regions that were marginal within Korea-China relations.

This study will contribute to extending the scope of the history of exchange between Chosŏn Korea and Ming China by taking a broader perspective.

I recently came across a book called Taste Luxury: Consumer Society and Scholar-officials in the Late Ming Dynasty.1 This is an excellent book written by Taiwanese historian Wu Ren-su (巫仁恕) from the viewpoint of economic and cultural history on the luxury trends among scholar-officials of the Ming dynasty. While this book offers ample descriptions of widespread luxury trends in the Ming Dynasty, my interest led me to ponder the account of Chosŏn garments being popular in Beijing in the fifteenth century. It was said that during the reign of Emperor Chenghua (成化, r. 1464–1487) and Emperor Hongzhi (弘治, r. 1487–1505), horsehair skirts imported from Chosŏn became highly fashionable and the Ming government enforced a prohibition against the custom. Wu Ren-shu uncovered clues from the Chinese historical records that Chosŏn clothing gained popularity in Beijing during the Ming Dynasty. The fact that it has never been examined by a historian of Korea makes the matter all the more interesting. Wu Renshu’s book confirms that ‘Chosŏn clothing fever’ previously existed among the civilians and scholar-officials of the early Ming period.

However Taste Luxury was not intended as academic research offering an in-depth analysis of Chosŏn attire. As the book refers to Chosŏn garments merely in the process of introducing the overall culture of consumption and trends of the Ming Dynasty, an inherent limit exists regarding the examination of the horsehair skirt. Taste Luxury presents only a handful of historical sources and omits descriptions of the form or shape of the skirt.

As a researcher on the history of Korea-China relations, I began to examine in detail the parts that were briefly covered in Wu's study, especially the theory that the skirt was introduced from Chosŏn and became widely popular in Beijing. In order to verify whether this form of clothing was indeed introduced from Chosŏn, I first examined its production and popularity in Chosŏn. For this purpose, additional historical materials produced during the Chosŏn period were searched to determine the correlation between the horsehair skirt and the Chosŏn Dynasty. Next, I reconsidered the theory that horsehair skirts were a popular trend in Beijing by critically re-examining the existing sources, analyzing the context of relevant records, and verifying the errors within texts. Furthermore, I confirmed the geopolitical relationship between 'the Ming Dynasty region where horsehair skirts were popular' and Chosŏn. As I proceeded with this study, I discovered a new aspect of cultural exchange between the two countries.

Therefore, I have organized this article in a narrative format that presents the “process of analysis”—gathering clues surrounding the Chosŏn horsehair skirt and approaching the historical reality of the fever for Korean clothing in the early Ming Dynasty. I believe a narrative structure of the analysis process can provide historical and reasonable theories in more abundance. This approach will lead us to a renewed understanding of the fashion trends in the fifteenth-century Ming Dynasty.

In many scholarly works on Sino-Korean relations, there has hitherto been an underlying assumption that only the land routes were used for cultural exchanges between the Chosŏn and the Ming dynasties throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. This is directly reflective of the common assumption that the official meetings of the envoys were the only channel for diplomacy, trade, and cultural exchange between the two countries. As a result, efforts to approach the historical meaning of numerous cultural exchanges made through other spaces or methods were insufficient, and it has not been able to advance to a more active and three-dimensional interpretation of Korea-China relations. However, cultural exchange has the potential to take place through various channels other than official routes. If we break away from the ‘conventional wisdom’ we take for granted and look closely at the historical materials of the time, we can discover various histories that took place in the past.

In this paper, first I review the contents and evidence about the horse-hair skirt referred to in Taste Luxury, and trace historical sources regarding horsehair skirts produced in Chosŏn. Next I investigate Ming Dynasty sources through a critical examination of the existing body of evidence and research, providing an alternative interpretation of the horsehair skirt fashion and the cultural interaction between Chosŏn and Ming. It is hoped that this article provides an opportunity to dive more deeply into the history of cultural and economic exchanges between the Chosŏn and Ming Dynasties.

Chosŏn Garments that Were Fashionable in the Capital during the Early Ming Period

(1) Mamigun in Taste Luxury

In Wu Renshu’s Taste Luxury, Wu describes a garment from Chosŏn as follows:

During the reigns of Emperor Chenghua and Emperor Hongzhi, horsehair skirts (馬尾裙, k. mamigun) imported from Chosŏn were widely popular. Miscellaneous Records from the Bean Garden shows the process of mamigun gaining popularity in Beijing at that time and then eventually being banned. Mamigun were first introduced to Beijing even before the Chenghua period, but as people did not know how to make them, the skirts were not popular from the beginning. Only after people began to weave and sell mamigun inside the capital walls did they become widely accepted. According to reports, this trend was so in fashion that a Chinese supervising secretary (給事中) made the following suggestion during the Hongzhi period: “Wearing mamigun is in such favor among the literati inside the capital walls to the extent that people are cutting off and stealing horsetail hair from the horses of government offices. These are disrupting the grand plan of lasting importance of the nation, and for this reason, I ask for its prohibition.” Only then were mamigun banned. This craving for foreign fashion disappeared under the strong interference and prohibition of the government.2

The quote from Wu shows that mamigun imported from Chosŏn were widespread in Beijing around the mid-to-late fifteenth century Ming Dynasty and that this skirt was made of horsehair. The popularity of the skirts was so extreme that the Beijing literati even conducted horsehair robbery, which eventually led to the Ming government prohibiting the wearing of mamigun. This is all the more noteworthy since this mamigun frenzy has remained unknown to historians of Korea. An in-depth examination of this matter will shed new light and reveal exciting facts.

Wu Ren-shu used two historical sources; the first is The Miscellaneous Records from the Bean Garden (菽園雜記, c. Shuyuan Zaji) composed by a fifteenth-century Ming government official named Lu Rong (陸容). The following passage is from an article on Chosŏn attire from Shuyuan Zaji:

-

a) Mamigun first made in Chosŏn appeared in the capital (京師). Residents of the capital bought them to wear, but no one yet knew how to weave them. At first, only the wealthy merchants and aristocrats along with singer-entertainers wore them, but afterward, military officers wore them too. Some people started making mamigun [of their own] and sold them. As days passed, more and more people came to wear mamigun, including many government court officials by the end of the Chenghua period. Those who wear extravagant clothing on their bottoms merely pursue beauty.

An elderly statesman (閣老) [called] Wan An (萬安) did not take off his mamigun whether it was summer or winter, and Minister of the Board of Rites (禮部尙書) Zhou Hongmo (周洪謨) wore two layers on his waist. Among young marquises (侯) and earls (伯) or royal in-laws, some even strung the hems together with bows. The only high officer who did not wear mamigun was the senior second-rank assistant chancellor of the Board of Personnel (吏部侍郎) Li Chun (黎淳).

This [phenomenon] was [the work of the] alluring spirit of clothing (服妖). It was not until the early years of Emperor Hongzhi that regulations for prohibition appeared.3

According to the above record of the Ming government official Lu Rong, the mamigun skirt was introduced from Chosŏn to the Ming capital and was first worn by affluent merchants and aristocrats, then it spread to military officials and finally to civil officials. Since mamigun were rather extravagant, Lu Rong observed this phenomenon with a critical attitude and further described it as being due to the “alluring spirit of clothing.” Eventually, mamigun were banned early in the reign of the Ming Emperor Hongzhi.

The second historical source is the Outline of Conversations: Old and New (古今譚槩, c. Gujin tangai) written by Ma Menglong (溤夢龍, 1574–1646). In his book, Ma Menglong says that “the literati in the capital favored mamigun and cut off horsetails [to make them], and since this disrupted the grand plan of lasting importance for the military and state, a request was made for their prohibition.”4 However, since this material was written in the seventeenth century, it can be considered as supporting evidence but is not sufficient to reflect the situation of our period of interest accurately.

The work of Wu Ren-shu ends here. This research has intriguing implications regarding the craving for Chosŏn fashion in the Ming Dynasty, but the brief analysis is somewhat unsatisfying. There is only one piece of historical evidence from the fifteenth century that proves the popularity of Chosŏn mamigun in Beijing. Therefore, how mamigun fashion of the Ming Dynasty was viewed in Chosŏn and whether this phenomenon indeed existed awaits further examination.

(2) The Absence of Mamigun from the Records and Relics of Chosŏn

Now let us try to find traces of mamigun in Korean historical accounts. One cannot help but wonder what position and status this attire, regarded as fashionable in the capital of the Ming Dynasty during the Chenghua period, had in the history of Korean clothing and ornaments, and how this garment was evaluated and how widely it was worn at the time. I set out to explore the traces of mamigun in Chosŏn records.

However, clothing with the name of mamigun does not appear in records produced in the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Chosŏn. There is no trace of mamigun in the Veritable Records of the Chosŏn Dynasty (朝鮮王朝實錄) or private records of diplomatic envoys (使行錄), or even in written collections (文集) made by various scholar-officials. Chosŏn clothing was prevalent in Beijing, yet Chosŏn officials failed to mention it. How should we react to the fact that this news, which nowadays clearly would make international headlines, was neglected? To properly evaluate this situation, we must consider the frequency of diplomatic envoys to Beijing and the importance they placed on gathering information on the Ming Dynasty.

The Chosŏn government dispatched four to nine envoys annually to Beijing in the fifteenth century, and the average number of dispatches during the reign of Emperor Chenghua was 4.4.5, As it took approximately five months for a single diplomatic envoy to travel back and forth between Seoul and Beijing, Chosŏn envoys stayed somewhere within the borders of China all year round. Also, since a single envoy remained in Beijing for thirty to fifty days, Chosŏn envoys were in Beijing for four to seven months every year. The diplomatic envoys obtained all possible information regarding affairs in the Ming Dynasty during their lengthy stay. They even copied official documents of the Board of Rites and daily court reports (朝報).6 Gathering information was the primary task of a Chosŏn diplomatic envoy. If the envoys had noticed this ‘Korean clothing fever’ they would have reported it back to the king and the royal court.

I could not rule out the reasonable doubt that the mamigun that prevailed among the Ming upper-class might have left traces somewhere in the Chosŏn records. For this purpose, the possibility of Han Kyeran (韓桂蘭) wearing mamigun was considered. Han Kyeran, born in Chosŏn as the sister of Han Hwak (韓確), was sent to Ming as female tribute (貢女). She became an imperial concubine of the Fifth Ming Emperor Xuande (宣德帝) and raised the Eighth Ming Emperor Chenghua. Because of this, she was respected by the Ming imperial household and enjoyed authority and power in the years of Chenghua.7, Han Kyeran, colluding with Chŏng Tong (鄭同), a royal eunuch originating from Chosŏn, demanded that the Chosŏn government send various clothes, ornaments, and food.8, Since mamigun were popular during the reign of Chenghua, there was a possibility that Han Kyeran, residing in Beijing at that time, might have requested such a skirt.9 However, among the wide range of items sent to her by the government, there were no mamigun or any garments similar to it. The Chosŏn government offered various clothes such as ramie cloth (苧布), cotton cloth (綿布), or hemp cloth (麻布), but neither mamigun nor horsehair were included on the list. It seems that Han Kyeran did not wear mamigun amid its peak in the capital of the Ming Dynasty.

Also, women’s clothing worn during the early Chosŏn period was examined. If the garment were indeed famous in Ming, it would have been worn in Chosŏn, and its traces would be found in the relics of women’s clothing excavated from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Nevertheless, no mamigun or any skirt of similar form was detected in the garments excavated from the early Chosŏn period.10

So, how can we explain that mamigun, a garment that is said to be from Chosŏn, appears only in Chinese historical sources, yet its traces are missing from the records or relics of the Chosŏn dynasty? Considering the historical significance of the records of the Veritable Records of the Chosŏn Dynasty, it is difficult to understand why mamigun remained unmentioned in the royal courts of Chosŏn. At this point, it is highly possible that the account of Shuyuan Zaji claiming that mamigun were garments from Chosŏn was a rumor and that Lu Rong left inaccurate information in his collection.

Tracking Mamigun

(1) Further Traces of Mamigun

Since there was no mention of mamigun in the archives of Chosŏn, I decided to gather more accounts from Chinese historical sources, of which priority was given to records produced in the fifteenth century rather than later materials. In this process, another source regarding mamigun surfaced. Wang Qi (王錡, 1432–1499) mentioned mamigun as follows in his book Miscellaneous records from staying in the field (寓圃雜記, Yufu zaji):

b) The structure of the hair skirt (髮裙, k. palgun, c. fagun) consists of horsetail hair (馬尾) tied over the underwear. Those who are fat wear one skirt, and those who are slim wear two or three skirts, making the overall garment like an umbrella.11

In this passage, Wang Qi identifies mamigun, or horsehair skirts, as fagun, or hair skirts. This new clothing from overseas was given various names; Lu Rong emphasized the original material and called it mamigun, while Wang Qi focused on the form of the horsetail hair and called it fagun. This source confirms that “gun (裙),” which literally means either skirt or underskirt, was in this context underskirt. The function of mamigun is also revealed. Unlike cotton cloth and silk, a horsehair underskirt is stiff and structured, causing the outer skirt to spread out widely, resembling an umbrella. Therefore, fat people wore one while slim people wore a couple of layers.

The mamigun worn in Chosŏn and Ming were similar to the crinoline popular among women of European countries in the nineteenth century. A crinoline is a petticoat designed to hold out the skirt and was worn by women of different status—from the Queen of England to aristocrats and the bourgeoisie. Although the precise methods of manufacturing the skirts in Asia and Europe would have been different, the fact that “horsehair” was used to weave both skirts is noteworthy.12 The analysis of mamigun from the perspective of clothing history is intended to be dealt with in the following study.

Can we find more traces of mamigun in the Chinese archives?

Ming Emperor Xianzong’s Tour of the Lantern Festival is a long scroll drawing of 37 cm [14.5 inches] in length and 624 cm [245.7 inches] in width. Figure 1 consists of partial images of the scroll. The National Museum of China, which has ownership of this painting, explains that it depicts Emperor Chenghua enjoying the first full moon of the lunar year in the imperial palace in 1485. In the images, eunuchs and palace maids are portrayed wearing skirts that look like umbrellas spread out. They are in fact wearing mamigun. Using this painting as evidence, the National Museum of China stated that mamigun were in fashion in Beijing.13 It seems indisputable that mamigun were popular in the years of Emperor Chenghua, as can be confirmed in the two literary accounts (a and b) and a painting dated from the fifteenth century, all examined above.

(2) Records Discovered in Suzhou (蘇州)

Some Chinese historical records were supplemented in the course of my search, but mamigun were nowhere to be found in the archives of Chosŏn so I began to re-investigate the Chinese records in which mamigun were mentioned. Lu Rong, the author of Shuyuan Zaji, was the first to be examined. Lu Rong was born in Taicang (太倉) in Suzhou Prefecture (蘇州府) and became a literary licentiate (進士) in 1466. He was appointed Secretary of Nanjing (南京主事) and then Director of the Bureau of Operations of the Ministry of War (兵部職方郎中), and afterward he obtained the post of Right Administration Vice Commissioner of Zhejiang Province (浙江布政司右參政). He died in 1494.14, The writer of Yufu zaji, Wang Qi, was also investigated. As he did not hold any official post during his whole career, Wang Qi called himself “a reclusive scholar of reed hermitage” (葦庵處士). He was also known as “an ascetic dreaming in Suzhou” (夢蘇道人) since he came from Changzhou District (長洲縣) in Suzhou Prefecture.15, Finally, Ma Menglong, a seventeenth-century figure who had also mentioned mamigun, was a novelist from the late Ming Dynasty and was also born in Changzhou District in Suzhou Prefecture.16, There is a striking commonality between these three people who left records of mamigun: Lu Rong, Wang Qi, and Ma Menglong all originated from Suzhou in the Jiangnan (江南) area. Lu Rong served in Nanjing during the reign of Emperor Chenghua, and Wang Qi was a resident of Suzhou. There was even an academic project carried out under the title “Ma Menglong and the culture of Suzhou.”17

The painting Ming Emperor Xianzong’s Tour of the Lantern Festival was also re-examined. Although the author and the time of production are yet not established, the site of its discovery is known: Suzhou in Jiangsu Province. The painting depicting mamigun was found in Suzhou thus all references to mamigun origininated from the region of Suzhou. This clue is important to solving the mystery of mamigun, but on the other hand, it can be estimated as an extremely “unusual” incident. Finding records of Chosŏn garments in southern China is extraordinary, since there were neither legitimate nor possible ways for the Chosŏn people to travel to southern China around the late fifteenth century, as can be affirmed by those who are familiar with Korean-Chinese relations during the Ming period.

The Ming Dynasty implemented an excessively restrictive foreign policy. Foreigners were prohibited from openly entering the country or conducting trade, and only envoys with tribunal missions were given admission. Moreover, the ports to be entered and cities and roads to be used by the tribunal envoys were designated beforehand and strictly regulated. After the Ming dynasty moved the capital from Nanjing to Beijing in 1421, Chosŏn envoys had to go through immigration procedures at Liaodong(遼陽) in Liaodong Province and go through Shanhai Pass (山海關) to reach Beijing. Koreans never had an opportunity to observe China except for the roads along Liaoyang and the Shanhai Pass leading to Beijing around the late fifteenth century. During the Tang(唐), Song(宋), or Yuan(元) dynasties, foreigners could travel and trade in the mainland of China, but this was basically impossible in the Ming dynasty. The records of Chosŏn garments all surfaced in Suzhou, despite that chances of Koreans and Suzhou people legally meeting there being very slim. The implications of this phenomenon are yet to be uncovered.

The “Jiangnan (江南, k. Gangnam) Style” of Ming, Mamigun

(1) Interaction between Cheju and Jiangnan

As the investigation developed, I came to the conclusion that “the capital” cited in Lu Rong’s writings was not Beijing but Nanjing. Lu Rong himself never referred explicitly to Beijing; he merely stated that “mamigun were popular in the capital.” It was Wu Ren-shu who interpreted the capital as Beijing. “Kyŏngsa (京師, c. jingshi, literally meaning ‘a capital of a country’)” is likely to be considered as Beijing. And considering the research on Korea-China relations so far, it is a very natural interpretation to recognize “the capital (京師)” where Chosŏn costumes were popular as Beijing.

However, the first capital of the Ming Dynasty founded by Emperor Hongwu (洪武帝) was Nanjing. The Third Emperor Yongle (永樂帝) moved the capital to Beijing in 1421. After the transition, Nanjing served as the secondary capital for the remainder of the dynasty, forming a system of “two capitals (兩京).” Therefore, residents of Jiangnan continued to call Nanjing “the capital.”18

The following article in the Veritable Records of the Chosŏn Dynasty provides us a crucial clue regarding the possibility of the capital being the Jiangnan region of China:

-

c) Specially Promoted Officer (特進官) Yu Chakwang (柳子光) said, “Your servant heard that Cheju is significantly distanced from Seoul and the beneficial influence of the sovereign (王化) have not yet reached [the area]. Local magistrates conduct numerous illegal acts and weave horsehair clothing (鬃衣, chongŭi). Because of this, horsetail and mane are clipped off and taken away, and almost all of them no longer exist.

Ch’oe Pu (崔溥) had drifted from Cheju to China. Someone asked, “Have you brought chongŭi with you?” He replied, “No.” Then the person who asked said, “When Yi Sŏm (李暹) came the other day, he sold a vast amount of chongŭi, yet you alone do not have any. You are indeed a scholar of poverty.” From this, one can see that since no one prosecutes [the law] in Cheju, local magistrates conduct illegal acts recklessly without any reluctance. … The King said, “It is appropriate to ban [the making and selling of] chongŭi completely. Deliberate and report upon the matter of appointing a concurrent overseer of stud farms (兼監牧).”19

The above article is a conversation between King Sŏngjong and Specially Promoted Officer Yu Chakwang in 1490 (Sŏngjong, Year 21; Hongzhi, Year 3). Several facts can be confirmed using this article. First, clothing made of horsehair like mamigun indeed existed in Chosŏn, but it was called “chongŭi” instead of “mami.” “Chong (鬃)” has the same meaning as “mami (馬尾)”; both refer to horsehair.

In the passage cited, Yu Chakwang is criticizing Cheju magistrates for breaking the law to make clothing from horsehair.20, To emphasize his point, Yu Chakwang recalled an episode regarding the experience of a government officer named Ch’oe Pu, who had drifted from Cheju Island to the Jiangnan region of China and then, after much suffering, returned to Chosŏn. A more detailed explanation would be something like this: Ch’oe Pu was appointed as special royal commissioner to track down criminals (推刷敬差官) on Cheju Island, but in the following year, his father passed away and he had to come back for the funeral. During his travel by boat leaving Cheju, there was a ferocious storm. After being adrift at sea for 14 days, he managed to reach the coast of Niutou waiyang (牛頭外洋) in Taizhou Prefecture (台州府). This region is currently known as Taizhou City (台州市) in Zhejiang Province, which is within the territory of the Jiangnan area.21, Cities with historical records associated with mamigun and chongŭi are marked on Map 1.

After his arrival on the coast of China, Ch’oe Pu was asked if he had “brought with him chongŭi” by the Chinese people he met while he traveled through the Jiangnan regions, including Hangzhou (杭州) and Suzhou. This incident shows that “clothes made of horsehair” were viewed as Chosŏn clothing in Jiangnan society. This information corroborates the earlier statement in article (a) that mamigun were introduced from Chosŏn. The Chinese asked for chongŭi as soon as they encountered Ch’oe Pu, a Korean.

When the Chinese learned that Ch’oe Pu did not have any chongŭi in his possession, they said, “When Yi Sŏm came the other day, he sold a vast amount of chongŭi, yet you alone do not have any. You are indeed a scholar of poverty.” The person mentioned by the Chinese, Yi Sŏm, existed in reality. Yi Sŏm was the magistrate of Chŏngŭi District (旌義縣監) on Cheju Island. In 1482, he also had drifted to the current location of Changsha District (長沙鎭) in the City of Nantong (南通市) in Jiangsu Province (江蘇省) due to bad weather. The location of Nantong can also be found in Map 1. Yi Sŏm also reached the Jiangnan area and then was repatriated to Chosŏn via Beijing.22 Cheju magistrate Yi Sŏm was carrying chongŭi in his ship, and the Chinese purchased this in 1482. When another Korean, Ch'oe Pu, drifted along the coast, the Chinese attempted to buy clothing made of horsehair from him too.

Cheju is the southernmost island of Chosŏn, far distant from land leading toward cultural gaps and information blockages. It was also the largest horse breeding site in Chosŏn, so the production of chongŭi was conducted regardless of its violation of the law. Mamigun’s absence from Chosŏn records and relics is quite natural if chongŭi were produced and circulated only in Cheju.23 Moreover, no Chinese had requested chongŭi from the Chosŏn envoys with valuable items who visited Beijing several times a year. On the other hand, both Yi Sŏm and Ch’oe Pu, who were worn out and shabby from their long journey, were asked for chongŭi in the Jiangnan region. It can be confirmed that chongŭi produced in Cheju were introduced to the Jiangnan area, driving the sensational trend.

In short, chongŭi produced on Cheju Island of the Chosŏn Dynasty created the mamigun trend that encompassed the Jiangnan area of the Ming Dynasty. Mamigun’s regional popularity helps us understand why mamigun were not mentioned in the intellectual network of Chosŏn diplomatic envoys that frequently journeyed to Beijing in the fifteenth century. As the pieces of the puzzle fall into place, the reality surrounding mamigun becomes more and more evident. Apart from the official transactions between the Chosŏn and Ming Dynasty centering around Seoul and Beijing, cultural exchanges between Cheju Island and the Jiangnan area, far from the political hub, indeed existed—an interesting feature to investigate.

(2) Is the Ming Emperor Xianzong’s Tour of the Lantern Festival really a Royal Court Painting of Beijing?

The mystery of mamigun still remains to be solved. The painting found in Suzhou in 1966 is thought to have been drawn by a local Jiangnan artist, but since the images of the painting depict the emperor and eunuchs residing in Beijing at that time, this also needs further examination. This is because, if this painting is a Beijing royal court painting, the premise that mamigun was in Jiangnan fashion could be shaken.

The painting is entitled “明憲宗元宵行樂圖,” which literally means “a painting of the Ming Xianzong (the posthumous title of Emperor Chenghua) enjoying the lantern festival (元宵, the night of the 15th of the first lunar month).” The author and date of the painting are unknown. The National Museum of China considers this as a royal court painting (宮中畵), produced by official court artists, and introduces it as a reproduction of the appearance of Beijing at the time.24 However, it would be unwise to draw such conclusion simply because a figure presumed to be an emperor is depicted. Images of the Lantern Festival in the palace can be recreated by anyone who has a reasonable imagination; however, the subject in question is dignified. Therefore, to claim that this is a genuine royal court painting, it must be proven that it was painted by an official artisan painter affiliated with the government. Currently, the National Museum of China does not provide any specific historical evidence regarding the piece being a genuine royal court painting.

The following image is a clue that reveals the origin of the painting.

In the introduction of the Ming Emperor Xianzong's Tour of the Lantern Festival, a description of the paintings along with poems that correspond with each painting is assembled under the title “Landscape Paintings of the New Year Lantern Festival (新年元宵景图).” The above Figure 2 is the last part of the introduction. “Chenghua Year 21, the middle month of winter, auspicious day (成化 二十一年 仲冬吉日)” is written at the end of the sentence, and an imperial seal (寶) is stamped over the date, engraved with the letters “豊年賞玩之寶,” literally meaning “Seal of the Appreciation of Good Harvest.”

An Image of the Ending of the Introduction from the Ming Emperor Xianzong's Tour of the Lantern Festival (明憲宗元宵行樂圖), Collection of the National Museum of China

The emperor’s royal seal was affixed to various documents produced by the government in Beijing. Since this painting bears a seal that only members of the royal family could use, the letter engraved in this seal must be cross-checked with the royal seals used by the emperor.

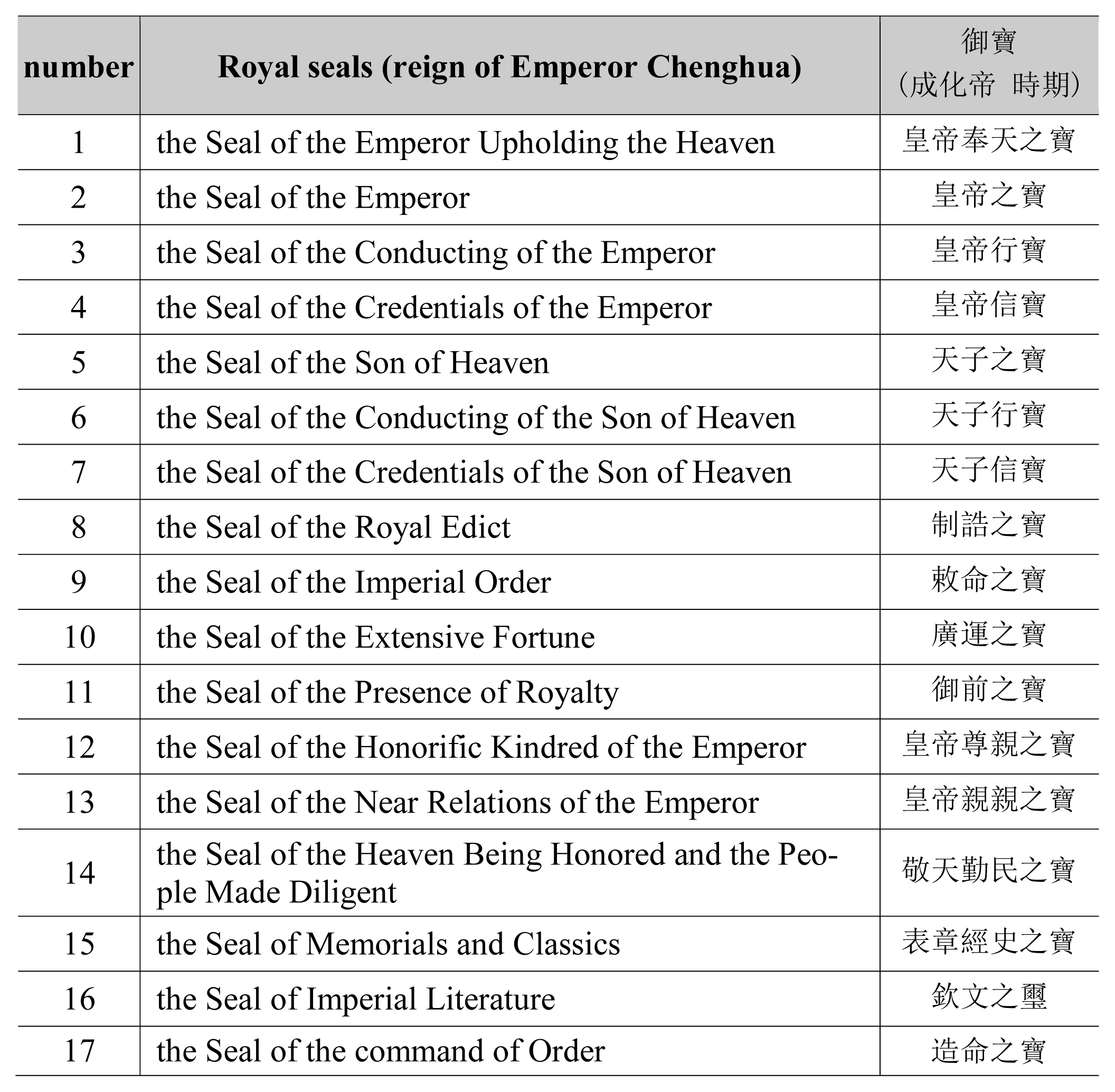

According to the Collected Statutes of the Great Ming (大明會典), the total number of royal seals used during the reign of Emperor Chenghua was seventeen. This is shown in Figure 3 below.

Shen Shixing, Da Ming Huidian (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1995): 626; Zhang Tingyu, Ming Shi 1: 29641.

Among the seventeen royal seals in Figure 3, the Seal of the Appreciation of Good Harvest does not exist, nor does it suit the formality of the other seals used by the emperor. The Ming Emperor Xianzong's Tour of the Lantern Festival is not, after all, a royal court painting. The type of royal seals used by the Ming imperial family leads us to confirm that this painting was not produced officially in the royal palace of the Ming Dynasty. Academia should stop claiming that the painting is a embodiment of the Ming dynasty of Beijing.

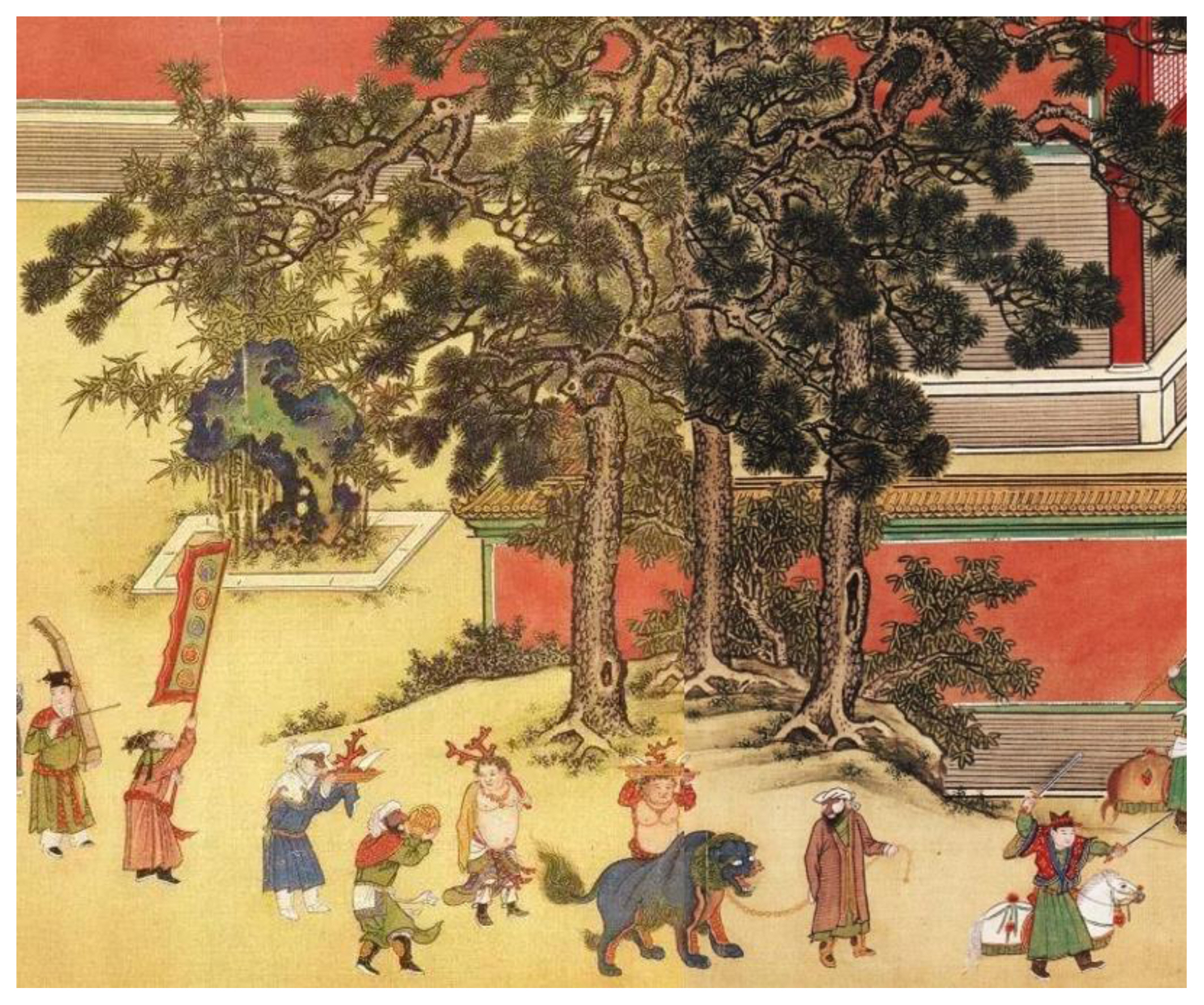

Meanwhile, the Ming Emperor Xianzong's Tour of the Lantern Festival depicts foreign envoys from the western regions with lions enjoying the Lantern Festival. However, this scene is unrealistic according to the foreign policy and regulations regarding foreigners inside the walls of Beijing implemented by the Ming authorities. The government did not permit foreign envoys to go around Beijing due to its fear that foreigners and civilians might threaten national security. Except for official events such as attending the court assembly, sight-seeing in Beijing was thoroughly banned. Foreigners were to stay in their accommodations, and Ming officials’ permission was required if they were to go outside however briefly.25, Therefore, it is implausible that envoys from different countries gathered and paraded in Beijing, as shown in Figure 4. This detailed examination uncovered errors in the presentation of Beijing society. This painting should no longer be regarded as an expression of Beijing society of Ming dynasty.

Partial Image of the Ming Emperor Xianzong's Tour of the Lantern Festival (明憲宗元宵行樂圖), Collection of the National Museum of China

Next, at the end of the painting, two other seals are stamped. The first seal, “西湖篆玉賞鍳,” means “the impression of Zhuanyu from the West Lake.” The West Lake (西湖) refers to the lake west of Hangzhou in Zhejiang province, representing the Jiangnan area of China. The National Museum of China presumes that Zhuanyu is Shi Zhuanyu (釋篆玉, 1705–1767), who lived in Hangzhou.26 The second seal, “江寧程氏德耆述夔藏,” means “stored by Deqi and Shukui of the Jiangning Cheng family clan.” Jiangning is the current Nanjing area. Cheng Deqi (程德耆) also had a connection with this painting.

In short, after looking at this picture in various ways, while the painting was not an officially commissioned court painting made in Beijing, and its site of storage and excavation indicates its strong connection with the Jiangnan area. This painting naturally projects the culture, customs, and trends of southern China. The artist adopted the mamigun fashion widely enjoyed in the region at the moment in order to express the most splendid and glamourous adornments one could imagine in the place of entertainment for the emperor during the Lantern Festival. This painting is a clue to the customs and fashion culture of the Jiangnan area in the early Ming Dynasty.27

The Year 1488: The Corruption Scandal and the Prohibition of Mamigun

The alluring Chosŏn mamigun were popular in the Jiangnan area but disappeared from history when the Beijing court banned the custom. Let us turn our attention to Beijing in order to examine the dispute surrounding the prohibition of mamigun.

In 1487, Emperor Chenghua passed away after ruling for 23 years, and Emperor Hongzhi acceded to the throne. When a new emperor is crowned, an atmosphere of reform and transformation is likely to arise. After the succession of Hongzhi, civil servants began to criticize and politically attack corrupt officials from the previous regime. It was the unofficially appointed official (傳奉官, k. chŏnbonggwan) system that mainly surfaced as problematic. The post of chŏnbonggwan, first established in February 1464 during the reign of Chenghua, referred to officials appointed by the emperor himself without formally undergoing the civil service entrance procedure. The emperor and his close attendants gained profits from trafficking government positions, disturbing the order of state affairs and becoming the root of corruption.28, Wan An, Li Zisheng (李孜省), Yin Zhi (尹直), Liu Ji (劉吉), and Peng Hua (彭華), along with eunuchs from that time, pandered to this system and consolidated their power. This system continued to exist during the years of Chenghua.29

When the new reign started, the Supervising Secretary of the Office of Scrutiny for Personnel (吏科給事中) Song Cong (宋琮) exposed the wrongdoings of the Minister of the Board of War (兵部尙書) Yin Zhi, Vice Minister of the Board of Rites (禮部侍郞) Huang Jing (黃景), and Censor-in-chief (都御史) Liu Fu (劉敷), and insisted that they be punished.30, The Regional Investigating Censor of Zhili (廵按直隸御史) Jiang Hong (姜洪) also participated in criticizing them by submitting a written statement.31

It was in this very context that the discussion of mamigun surfaced. The specific details are as follows:

d) Investigating Censor (監察御史) Tang Nai (湯鼐) said, “…… Minister of the Board of Rites (禮部尙書) Zhou Hongmo (周洪謨) has no laws in governing his house. He clings to those in power, saying that they should flatter when they are prosperous and shun them when they are weak. …… Left Vice Minister (左侍郞) Zhang Yue (張悅) had worn horsehair underskirts (馬尾襯裙, k. mami-ch’in’gun) while holding the post of Assistant Censor-in-chief (僉都御史). Despite his status as a government officer, he had the extravagant appearance of a dressed-up man of the street. Minister of the Nanjing Ministry of War Ma Wensheng (馬文升) was appointed to the War Section (兵曹) and proceeded to the garrisons (鎭), but he also was extravagant and obscene. Junior Mentor (少傅) Liu Ji (劉吉), Wan An, and Yin Zhi are all dishonest and covetous. Both Wan An and Yin Zhi are to be removed [from their posts] …… The Emperor said, “Confer the Old Law (舊典) and let the appropriate officials perform the tasks. From now on, those who wear clothing of mamigun shall be arrested by Imperial Bodyguards (錦衣衛), and as the remaining is all hearsay (汎言), it is denied.”32

The above article (d) is an entry from Hongzhi, Year 1 (1488), Month 1. In the article, Investigating Censor Tang Nai insists on punishing the depraved officers Wan An, Zhou Hongmo, Yin Zhi, and Liu Ji, who came to power during the reign of Emperor Chenghua, while citing the misdeeds of other officials alongside. Among the charges, he criticizes Left Vice Minister Zhang Yue for wearing mamigun. Zhang wore horsehair underskirts when he was Assistant Censor-in-chief and was detested for extravagantly dressing like a man with no dignity in the streets.33, Who is this Zhang Yue? Zhang Yue (1426–1502) was from Huating (華亭) in Songjiang (松江), currently the Shanghai (上海) region. He acquired his literary licentiate in 1460, served as Secretary of the Board of Justice (刑部主事), and gained the official post of Assistant Censor-in-chief during the reign of Chenghua.34 He also came from Shanghai, and being a local of an area neighboring Jiangnan, he was following the fashion of his hometown during his years as Assistant Censor-in-chief. Even in Beijing, only those from the Jiangnan area were wearing mamigun.

However, Lu Rong wrote in Shuyuan Zaji that the high officers Wan An and Zhou Hongmo in Beijing also wore mamigun. There is a discrepancy between Lu Rong’s record and the written statement of Investigating Censor Tang Nai. Yet, it is unlikely that Tang Nai deliberately omitted Wan An and Zhou Hongmo wearing mamigun, sparing his criticism. Since Wan An was a figure of immorality who sought power by taking bribes, Tang Nai was determined to eliminate him.35, Tang Nai would have indeed mentioned him wearing mamigun if he had worn it. Any shortcomings of Wan An were likely to be listed as reasons for his removal. According to Tang Nai, Zhang Yue, who was not involved in the corruption scandal, was wearing mamigun and was criticized for this. However, Wan An and Zhou Hongmo were excluded from the accusation. This is because Wan An did not wear mamigun.36

Considering the political dynamics of the era along with the nature of the Veritable Records of Ming (明實錄, Shílù of Ming ), which recorded the written statements of officials and responses of the emperor on the spot, the corrupt officials Wan An and Zhou Hongmo had not worn mamigun. Only Zhang Yue, from the Jiangnan, wore mamigun. Later in his life, while he was Right Administration Vice Commissioner of Zhejiang province, Lu Rong suggested there were some political problems within the province and was dismissed from his post. Lu Rong from Suzhou, who had an upright personality, criticized and avoided the fashion of mamigun amid its high popularity. 37 He apparently conceived mamigun as a symbol of officials prone to wealth and corruption.

In the fifteenth century, the controversy over mamigun was not in itself a primary issue. It instead surfaced in the course of listing officials’ ill behavior to politically eliminate corrupted officials and restore the discipline that had slipped so dangerously during the reign of Emperor Chenghua. The seventeenth century historical documents recorded that “the popularity of mamigun drove people to cut off horsehair, which sparked a public outcry, demanding that mamigun should be forbidden.”38 This may have been the more practical reason behind the prohibition of mamigun. Chongŭi (鬃衣) was also banned in Chosŏn for the sake of horsehair preservation. Nevertheless, Investigating Censor Tang Nai and Director of the Bureau of Operations of the Ministry of War Lu Rong used mamigun to indicate and criticize bureaucrats for extravagance, among the various aspects of mamigun. Mamigun fashion, which once had dominated the Jiangnan area in the fifteenth century, met its fate and rapidly disappeared after the change in power and transition in policy in the Ming Dynasty.

Conclusion

This study delves into the relationship between the Chosŏn Dynasty and the upper-class fashion trends in the Ming while also questioning the framework employed in existing literature on cultural exchanges between two early modern East Asian dynasties, the Chosŏn and the Ming, thereby setting itself apart from conventional scholarship.

Cheju Island was used as a horse breeding region since the Yuan period and continued to produce the largest volume of horses during the Chosŏn period. Due to the significant amount of horses, commodities made of horsehair were mainly provided from Cheju Island. “Gat,” the traditional Korean hats worn by Chosŏn aristocrats, were made of bamboo and horsehair, and both the materials and final products primarily originated from Cheju.

However, it has been confirmed through this research that there was also clothing made of horsehair in Cheju that was until now unidentified by a academic community. This garment was introduced to the Jiangnan area through a rather obscure route. Cities with historical records associated with mamigun are marked on Map 2. Chosŏn civil servants who frequently traveled to Beijing in the fifteenth century did not have knowledge of mamigun. However, the Chinese told Chosŏn government officials who reached the Jiangnan area of southern China due to bad weather that they were willing to buy “clothing made of horsehair.” Among the drifters was Cheju magistrate Yi Sŏm carrying chongŭi on his boat, which he sold to the Chinese.

Mamigun were extremely popular throughout the Jiangnan area. First, female entertainers wore mamigun to express their beauty. Then, the custom gradually expanded to the wealthy class and military officials, and in the end, civil servants wore them, too. This horsehair petticoat gave the wardrobe a fashionable silhouette by supporting and fully spreading the outer skirt. The fifteenth-century mamigun of Asia are similar to the nineteenth-century crinoline worn by aristocrats and bourgeois women in European countries. The crinoline’s width and volume were often perceived as a symbol of wealth, which led to some side effects as skirts spread even wider and more fully over time. This research provides an opportunity for comparison of two types of clothes made of similar materials which enjoyed popularity in different worlds, the East and the West, during different time periods. The analysis of mamigun from the perspective of clothing history is intended to be dealt with in the following study.

Crinoline in nineteenth-century Europe was a symbol of extravagance. This was also the case in Asia in the fifteenth century; many officials looked upon this phenomenon with uncomfortable feelings. Chosŏn prohibited the production of chongŭi in order to preserve horsehair, whereas in Ming China, mamigun were not discussed merely in terms of reforming customs but were brought up in the process of a political dispute. With a new emperor enthroned, the Investigating Censor intended to dismiss corrupt government servants from the previous regime. Officials who wore the “foreign” and “extravagant” mamigun were also hit with other allegations. Mamigun were prohibited under the atmosphere of reform. It was not because of fashion itself that mamigun disappeared from history; mamigun were used for political purposes and evaporated for the same reason.

Meanwhile, this paper is also meaningful in that it corrects errors in the study of Ming dynasty costumes by analyzing the painting [Ming Emperor Xianzong’s Tour of the Lantern Festival] of the Ming Dynasty in detail and determining whether it was imperial paintings.

Mamigun is an interesting topic that gives us insight into the cultural exchange between the Chosŏn and Ming and can also be described as an episode that involves Cheju Island and Jiangnan of Ming, both regions that were marginal within Korea-China relations. In the 15th and 16th centuries, it was believed that Korea-China diplomacy and culture exchanged centered on the land route linking Seoul in the Chosŏn and Beijing in the Ming Dynasty, and little research on cultural exchanges between other regions was studied. However, mamigun fever was generated in the regional interaction between Korea’s southernmost Cheju Island and the Jiangnan region of China. This study is the first step in confirming the history of exchanges between Cheju Island, the southern tip of Chosŏn, and Jiangnan, an economic region of the Ming Dynasty. Furthermore, this study calls for a shift in analytical viewpoints on approaching Sino-Korean cultural exchange in the Chosŏn period: one, from center to periphery, and the other, from land to sea.

Notes

Wu Ren-shu, Pinwei shehua: Wan ming de xiaofei shehuì yu shidafu [Taste Luxury: Consumer Society and Scholar-officials in the Late Ming Dynasty] (Beijing: Chung Hwa Book Co., 2008).

Wu Ren-shu, Pinwei shehua, 125–126.

Lu Liu, Shuyuan Zaji [Miscellaneous Records from the Bean Garden] (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1995): 324.

Ma Menglong, Gujin Tangai [Outline of Conversations: Old and New] in Ma Menglong Quanji [Collected records of Ma Menglong] 6 (Jiangsu: Jiangsu guji chubanshe, 1993): 3.

Park Sungju, “Koryŏ chosŏnŭi kyŏnmyŏngsa yŏn’gu” [A Study on the Koryŏ and Chosŏn Envoys sent to the Ming Dynasty], Ph.D. diss, Dongguk University, 2004); Jung Donghun, “Chŏngt’ongjeŭi tŭnggŭkkwa chosŏn-myŏng kwan’gyeŭi k’ŭn pyŏnhwa” [Emperor Zhengtong’s Enthronement as a Turning Point in the Chosŏn-Ming Relationship] in Korean Culture 90 (2020).

Lee Kyuchul, “Chosŏnch’ogi t’aejo~sejongdae taeoejŏngbo sujiphwaltongŭi silsanggwa pyŏnhwa” [Collecting foreign information during the early days of the Chosŏn dynasty (from Taejo’s reign to Sejong’s)-how it proceeded, and how it changed] in Yŏksa wa hyŏsil 65 (2007); Koo Doyoung, “Sibyuksegi chosŏn taemyŏng sahaengdanŭi chŏngbosujipkwa chŏngboryŏk” [The Intelligence-Gathering Strength of the Chosŏn Envoys to Ming in the 16th Century] in Daedong Munhwa Yeongugu 95 (2016); Ding ChenNan, “Sibyuksegi chosŏn taemyŏng sahaengdanŭi chŏngbosujipkwa chŏngboryŏk” [Chosŏn Emissaries’ Intelligence - Gathering Activities of Chinese Tong-Bao during the 16–17th Centuries in Korean Culture 79 (2017).

Han Hwak was the maternal grandfather of King Sŏngjong of the Chosŏn Dynasty. Han Hwak’s sister was a concubine of the Third Emperor Yongle, and her younger sister became a concubine of the Fifth Ming Emperor Xuande. Han Hwak was offered the title of Vice Minister of the Court of Imperial Entertainments (光祿寺少卿) and enjoyed power in Chosŏn. (Lim Sanghun, “Myŏngch’o chosŏn kongnyŏ ch’injogŭi chŏngch’ijŏk sŏngjanggwa taemyŏngoegyohwaltong” [Political Growth and Diplomatic Activities of Families of the Female Tributes of Chosŏn in the Early Ming Dynasty] in Ming-Qing Historical Studies 39(2013), 11–13.

Sŏngjong Sillok, 74:8a (1476.12.16); Sŏngjong Sillok, 106:3a (1479.7.4).

Sŏngjong Sillok, 80:2a (1477.5.2); Sŏngjong Sillok, 95:12a (1478.8.13); Sŏngjong Sillok, 119:12a(1480.7.22.); Sŏngjong Sillok, 120:9a(1480.8.19); Sŏngjong Sillok, 157:18b(1483.8.18); Sŏngjong Sillok, 158:19b(1483.9.16); Sŏngjong Sillok, 158:21b(1483.9.17); Sŏngjong Sillok, 169:17a(1484.8.24).

Park Sungsil, “Chosŏnjo ch’ima chaego–sibyuksegi ch’ult’oboksigŭl chungsimŭro” [A Research of China in the Chosun Dynasty] in Journal of the Korean Society of Costume 30(1996); Ju Ranjeong and Kim Yongmun, “Chosŏnjŏn’gi ch’ult’o yŏsŏngboksigŭi yuhyŏnggwa t’ŭkchinge kwanhan yŏn’gu” [A Study on the Types and Characteristics of Women’s Costume Excavated in the Early Chosŏn Dynasty] in Journal of the Korean Society of Costume 67·1(2017).

Wang Qi, Yufu zaji [Miscellaneous records from garden]. (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1995): 523.

A crinoline is a type of petticoat, derived from the Latin ‘crinis (馬毛)’ and ‘linum (麻).’ The material itself was stiff due to a mixture of horsetail hair and hemp, making it possible to make skirts fuller without using auxiliary materials. Crinoline was made of hardened steel since the mid-nineteenth century. (Lee Minjeong, K’orŭsekkwa koraeppyŏ [Corset and Whale Bones] (Seoul: P’urŭndŭllyŏk), 2018, 202–203; Lee Jinsuk and Lee Jeongran, “K’ŭrinollin sŭt’ail mit pŏsŭl sŭt’ail chaek’idŭi p’aet’ŏnbunsŏkkwa chaehyŏne kwanhan yŏn’gu” [A Study of Crinoline and Bustle Style Jacket Pattern Analysis and its Reproduction] in Fashion & Textile Research Journal 8·1(2006)).

National Museum of China, Ruiquan Nafu - Wuxu Xinnian Guanzang Wenwuzhan [Lucky Dog, Accepting Good Fortune: New Year Exhibition of the Cultural Relic Collection]. (Suzhou: National Museum of China), 2018.

Zhang Tingyu, Ming Shi [History of the Ming Dynasty] 4 (Beijing: Chung Hwa Book Co.), 1974: 32083; Xiaozong Shílù of Ming (明孝宗實錄), 0187 (1488.1.12).

Li Jiefei, “WangQi ji qi 《Yupuzaji》” [Wang Qi and his Miscellaneous records from home garden] in Suzhou zazhi (2002), 49.

Oki Yasui, Minmatsuno Hagure Chishikinin-Liuuto Soshubunka Kōdansha Senshomechie no Shaohin Spetcu, [Intellectuals at the End of the Ming Dynasty - Ma Menglong and the Product Specifications of Suzhou Culture] (Tokyo: Kōdansha), 1995.

Oki Yasui, Minmatsuno Hagure Chishikinin..

Cho Younghun, “Wŏn·myŏng·ch’ŏng sidae sudo pukkyŏnggwa paedoŭi pyŏnch’ŏn” [Beijing and the Changing Auxiliary Capitals in Late Imperial China] in Yoksa Hakbo 209(2011).

Sŏngjong Sillok, 239:16a (1490.4.25).

Yu Chakwang did not specifically mention the form or shape of chongŭi because he was not interested in the clothing itself but focused on banning the ‘act’ of making clothing with horsehair.

Joo Sungjee, “Kugŭlmaebŭl hwaryongan ch’oebu p’yohaerogŭi nojŏng pogwŏn” [The Restoration of Choi Bu’s Path in Pyohaerok based on Google Maps] in The Journal of Korean Historical-forklife 57(2019).

Sŏngjong Sillok, 157:7b (1483.8.10).

Most of the existing records, such as the Chosŏn Wangjo Sillok and various literary works, were compiled by central government officials prioritizing Hanyang, and the excavated clothes are also included within the culture of the Land and not that of Cheju.

National Museum of China, Ruiquan Nafu - Wuxu Xinnian Guanzang Wenwuzhan.

Shen Shixing, Da Ming Huidian 3: 113, 475; Xiaozong Shílù of Mi ng, 3086(1501.1.23); Li Yunquen, Chaogong zhidushilun [Theories on the History of Tribute System] (Beijing: Xinhua chubanshe), 2004; Li Shanhong, “Mingdai huitongquan dui Chaoxianshichen menjin yanjiu” [The Problem of Chosun envoy's Entrance to the Meeting Hall in the Ming Dynasty] in Heilongjiang Social Sciences 132 (2012); Koo Doyoung, Sibyuksegi hanjungmuyŏgyŏn’gu [Research on Trade Relations between Korea and China in the Sixteenth Century] (Seoul: Thaehaksa), 2018, 97–109.

National Museum of China, Ruiquan Nafu - Wuxu Xinnian Guanzang Wenwuzhan.

This picture is not an official royal painting of Beijing in the Ming Dynasty, but it has a rarity that clearly displays the culture of the Ming Jiangnam area.

In 1483, Investigating Censor (御史) Zhang ji (張稷) submitted a written statement to Emperor Chenghua insisting that “Among civil servants, there are those who do not know how to read even the letter ‘丁’, and among military servants, there are those who never have even shot an arrow before.” (Xianzong Shílù of Ming, 4185 (1483.12.25)).

Zhang Tingyu, Ming Shi 5: 3403; Kang Jungman, Myŏngnara yŏktae hwangje p’yŏngjŏn [Biography of Emperors of the Ming Dynasty] (Seoul: Churyusŏng), 2017, 216–221.

Xiaozong Shílù of Ming, 0115 (1487.11.18).

Xiaozong Shílù of Ming, 0150 (1487.11.29).

Xiaozong Shílù of Ming, 0191–0192 (1488.1.19).

Shílù of Ming records ‘mamigun’ as ‘mami-ch’in’gun,’ explicitly indicating that this clothing functioned as an underskirt.

Zhang Tingyu, Ming Shi 3: 32906; Ming Xianzong Sillok, 4282 (1484.6.22).

Xiaozong Shílù of Ming, 0544–0545 (1489.3.11); Zhang Tingyu, Ming Shi 3: 30852–30853.

Wan An and Zhou Hongmo from Sichuan (四川) resigned from their government post in 1488 (Xiaozong Shílù of Ming, 1790 (1495.3.5)).

Wu Daoliang, “Lu Liu he tade 《Shuyuanzaji》” [Lu Liu and his Miscellaneous Records from the Bean Garden] in The Research on Ming Qing Dynasties Novels 60 (2011), 182–183.

Ma Menglong, Gujin Tangai: 3.