경주의 기념비적 고분: 사회-정치적 의미에 대한 논의

Monumental Burial Mounds in Kyŏngju: Remarks on their Socio-political Meaning

Article information

Abstract

현대 경주시 도심에 자리하고 있는 고분들은 고신라의 가장 인상적인 유적이다. 적석목곽묘에서 출토된 당대의 유물은 신라의 국가 형성의 특정 단계인 마립간 시기(356-514) 때 발생됐으며, 통치자의 칭호 또한 마립간이었다. 대단히 호화로운 부장품과 함께 거대한 규모를 자랑하는 몇몇의 특정한 고분들은 일반적으로 신라 지배층의 정치적 독립성과 힘을 반영하는 왕의 무덤으로 해석되어왔다. 그러나, ‘권력을 과시하는 무덤’이라는 개념을 도입한 배경에는 역설적으로 이 기념비적 고분의 존재를 이용하여 왕권을 더욱 공고히 하려는 의도가 담겨있는 바, 이 크고 화려한 고분은 오히려 당시의 높은 사회-정치적인 긴장의 표상이라 주장된다. 따라서 이 고분의 존재는 신흥세력의 정치적 약점을 나타내는 지표이다. 고구려 왕국과 대가족 간 경쟁으로 인한 외부의 압력은 이 고분 축조의 주요 원동력이다.

Trans Abstract

The mounded graves in the city center of modern Kyŏngju belong to the most impressive relics of Old Silla. These burials, constructed as wooden chamber tombs within a stone mound, occurred during a specific stage of Silla’s state formation, which is also known in reference to the ruler’s title as the maripkan period (356-514). Due to their gigantic measurements and their extremely lavish equipment, a small group of these graves has been commonly interpreted as royal tombs that reflect the political independence and strength of Silla’s elite. However, by introducing the concept of ‘ostentatious graves’ it is being argued that the monumental burials are rather an expression of high socio-political tension. Their existence is an indicator of the political weakness of the emerging polity. Pressure from the outside caused by the kingdom of Koguryŏ and inter-polity competitions of the leading families are identified as a major impetus for the construction of these graves.

Introduction

One of the most impressive experiences for visitors of modern Kyŏngju, the former location of the capital of the Silla kingdom, is a walk through the ‘Taenŭngwŏn Tomb Complex’ from the southern entrance, where with every step along the path more mountain-like burial mounds appear in front of the observer. At this place, the deeply rooted history of Kyŏngju becomes a direct experience. The question who was buried in these mounds is seemingly easy to answer: they must be the last resting places of Silla’s kings and queens. However, as has been understood for a while, most of the more than hundred-fifty barrows counted in the vicinity of Wŏlsŏng, the core of the ancient capital, were constructed in a rather limited time span, the so-called maripkan period, which lasted for a little bit less than 160 years (356–514 CE). Obviously, most of the graves must have been occupied by other individuals than the six, historically known rulers of that time. Differences in the size and the equipment of the burials have been commonly interpreted as related to the social status of the deceased.1 Although this assumption might not cause too much disagreement, it does not offer an explanation for the monumental measurements and the exceptional equipment that separate a small group of graves from the other mounds.

In the present article it will be argued that the construction of the monumental mounded graves can be understood as a reaction to political and social tension caused by factors from in and outside of the Silla polity. As a theoretical framework for the analysis, the concept of ‘ostentatious graves,’ described by the German archaeologist Georg Kossack, will be introduced. Examining the burials from this perspective challenges a number of commonly expressed assumptions on Kyŏngju’s mounded graves. As will be demonstrated, the historical value of the mounds rests, before all, in its potential to offer insights into the structural processes during Silla’s state formation.

Sources and Chronology of Early Silla

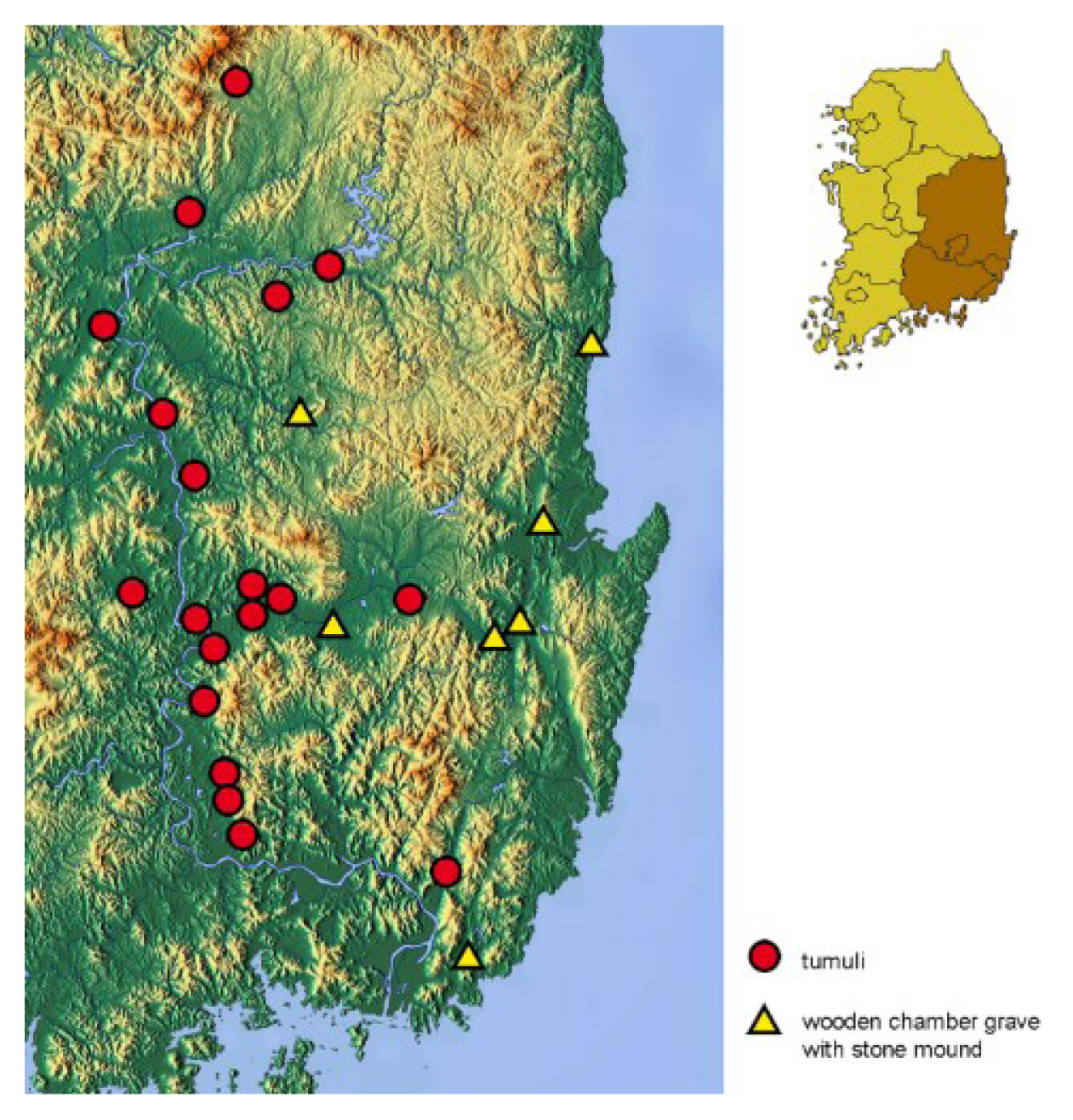

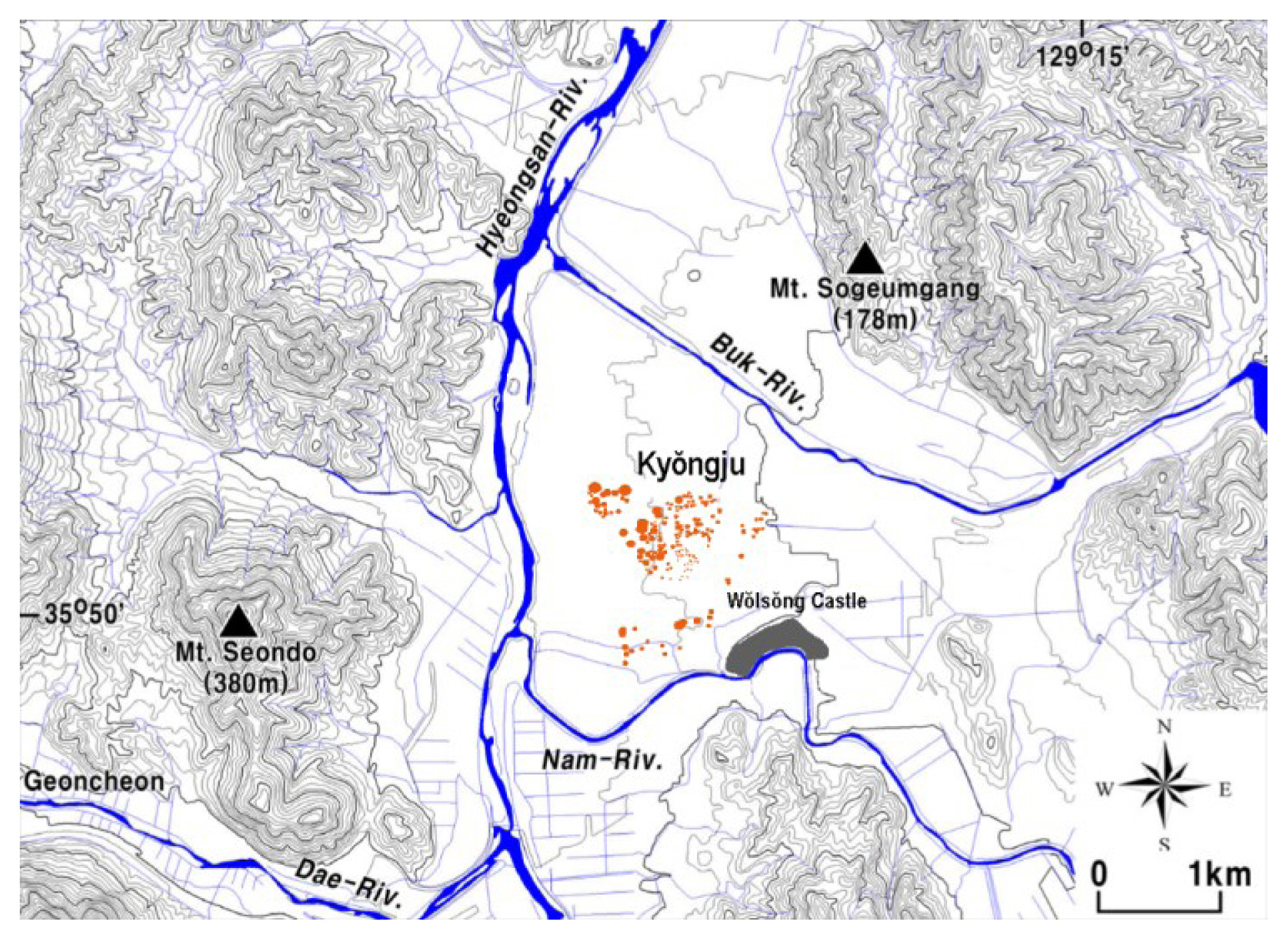

Before discussing the monumental graves in Kyŏngju in more detail, it seems to be necessary to provide a brief overview of basic facts and on views being held in the present article in order to set the foundation for the following argumentation. Today a small town in the southeast of the Korean Peninsula in North Kyŏngsang province, Kyŏngju, or more precisely its predecessor known as Saro, was the core and capital of the Silla kingdom. Archaeological remains of Silla can be found everywhere in the city, but the oldest, still visible structures of the capital are the earthen ramparts of Wŏlsŏng Palace and the burial mounds in its vicinity (fig. 1).

Topographic map of Kyŏngju with the location of Wŏlsŏng Palace and the mounded tombs of the northern cemetery.

Silla was, besides Koguryŏ and Paekche, one of the Three Kingdoms that were the dominant political units on the Korean Peninsula from the first centuries AD until Silla, with support of Tang China, defeated Paekche in 660 and Koguryŏ in 668. The Three Kingdoms period and there-with the history of Silla is covered by historical sources. The Samguk sagi (三國史記, ‘History of the Three Kingdoms’) and the Samguk yusa (三國遺事, ‘Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms’) are the most important. The time of the compilation of the Samguk sagi in 1145 and of the Samguk yusa in 1280, long after Silla and the other kingdoms had vanished from the political map, calls for caution in regard to historical accuracy. Critical examinations have proven particular portions of the sources – especially the older parts – as less reliable and biased, or in some cases even false.2, The few available contemporary scriptures from the Three Kingdoms period, for instance, epigraphic inscriptions such as the famous stele of King Kwanggaet’o or the stele of Naengsu-ri3 strengthen the impression that the Samguk sagi and the Samguk yusa provide a rather specific and certainly not comprehensive image of that time.

The historical development of Silla has been traditionally divided into three stages, namely the old, middle and late kingdom.4, The focus of the present study is on the so-called Old Silla kingdom. The main problem with this period is that there is no common agreement in research when the kingdom came into existence. According to the historical sources, Saro was founded in 57 BC through the union of six villages for the purpose of defending the region against enemies (Samguk yusa I.17; Samguk sagi I. Kŏsŏgan Hyŏkkŏse).5, This date, which renders Silla older than Koguryŏ (37 BC) and Paekche (18 BC) has been commonly refused as too early and it is one example of the biased historiography represented in the Samguk sagi and Samguk yusa. Presupposed the event that led to the foundation of Saro is true, there is no indicator that the new polity became immediately a kingdom. It has been assumed that the titles of the rulers stated in their accounts in the Samguk sagi and Samguk yusa offer hints at the development of the polity’s power structure.6, From the third ruler Yuri (r. 24–57) up to Naemul (r. 356–402), Silla’s leaders were called isagŭm which can be translated as ‘ruling elder’. From Naemul to Chijŭng (r. 500–514) the title of maripkan, a composition of marip translated as ‘highest level of authority’ and kan, a general title for rulers, was in use.7, Literally taken, the maripkan must have been the head of a group of people with high authority, a primus inter pares.8, During the reign of Chijŭng (r. 500–514) the title changed to the Chinese term for king (wang, 王)9, and historians do not consider Silla to be a full-fledged kingdom before the reign of Chijŭng’s successor Pŏphŭng (r. 514–540).10

At the current state of research, it is difficult from an archaeological perspective to deduce the emergence of the kingdom from the remaining material culture. The occurrence of the mounded tombs in the plain of Kyŏngju from the fourth century has been reckoned to be an indicator for the existence of a developed polity.11, Often, this polity is automatically equated with the kingdom, as can be seen in case of the burial mounds in Kyŏngju that date to the maripkan period, but are commonly referred to – not last because of their extraordinary grave goods – as royal tombs (wangnŭng).12, However, in consideration of the ruler’s title and the unclear status of the Saro-polity, this seems to be, as Kŭn-chik Lee (Geunjik Lee) has rightly pointed out, a rather anachronistic viewpoint.13

Mounded graves in Kyŏngju: An Overview

The mounded tombs in Kyŏngju belong to two basic grave types, which are the ‘wooden chamber tomb within a stone mound’ (積石木棺, chŏksŏng mokkwanmyo)14, and the ‘stone chamber grave with corridor.’ The latter occurs after the maripkan period and is not further discussed in the present study. The wooden chamber tombs within a stone mound are a regional phenomenon which is limited to a few areas of the historical Yŏngnam region in southeastern Korea (fig. 2).15

These mounded graves coexist with a number of other burial types that can occur at the same site.17, The importance of the mounds is rooted in their sudden occurrence, in the novelty of their construction method, in the fact that particularly big burial mounds were constructed in this way, and that these big sized graves were equipped with exceptional goods. In accordance with Pyŏng Yŏn Ch’oe (Byunghyun Choi), one of the most famous and influential scholars of Silla burials, the basic features of the stone mound tombs can be described as follows: they consist of a more or less sunken grave-pit, a wooden grave chamber which is embedded in a package of stones and covered by a stone mound. This stone mound is mantled by an earthen layer and the outline of the tumulus is marked by a stone setting (fig. 3).18

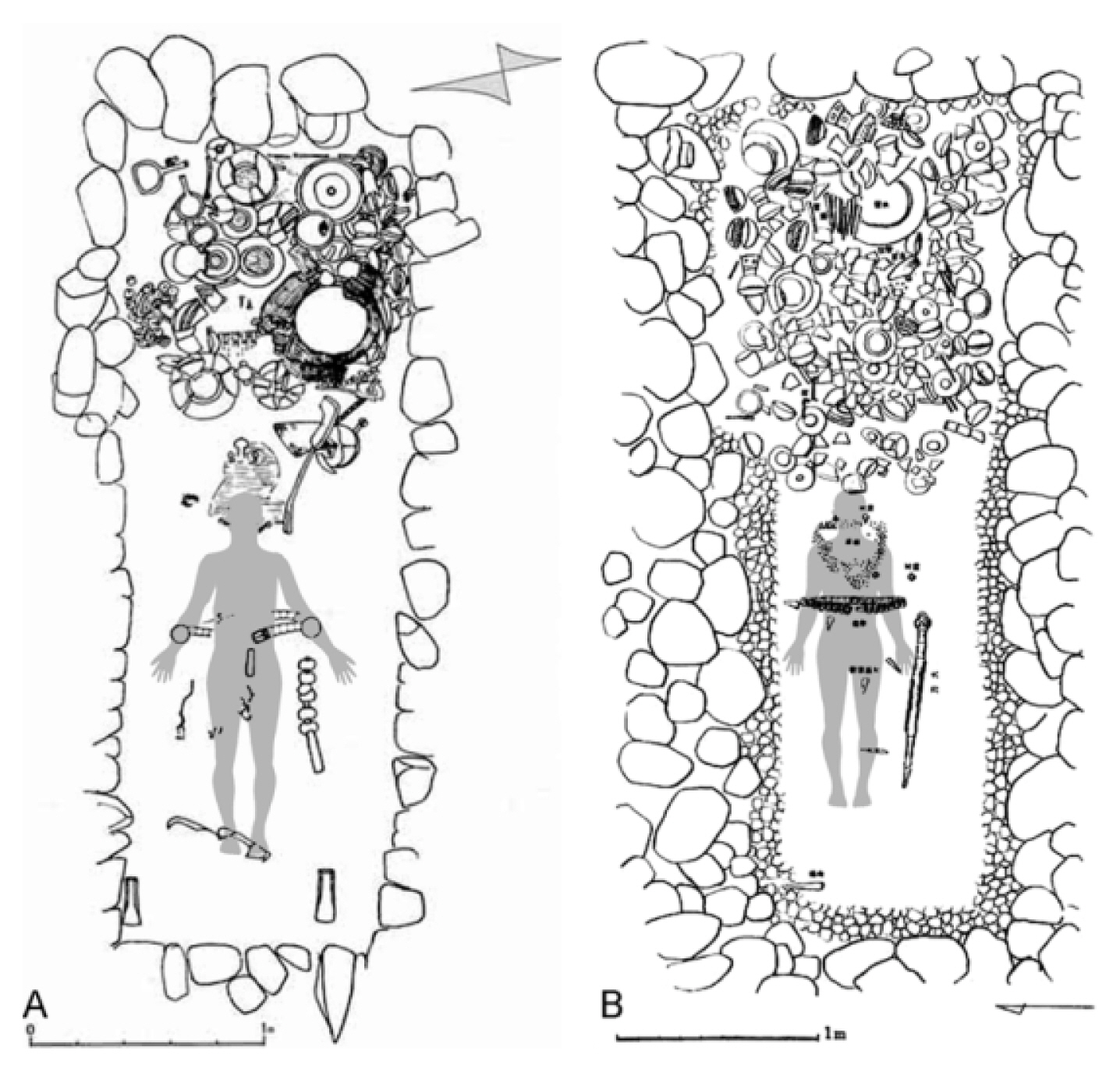

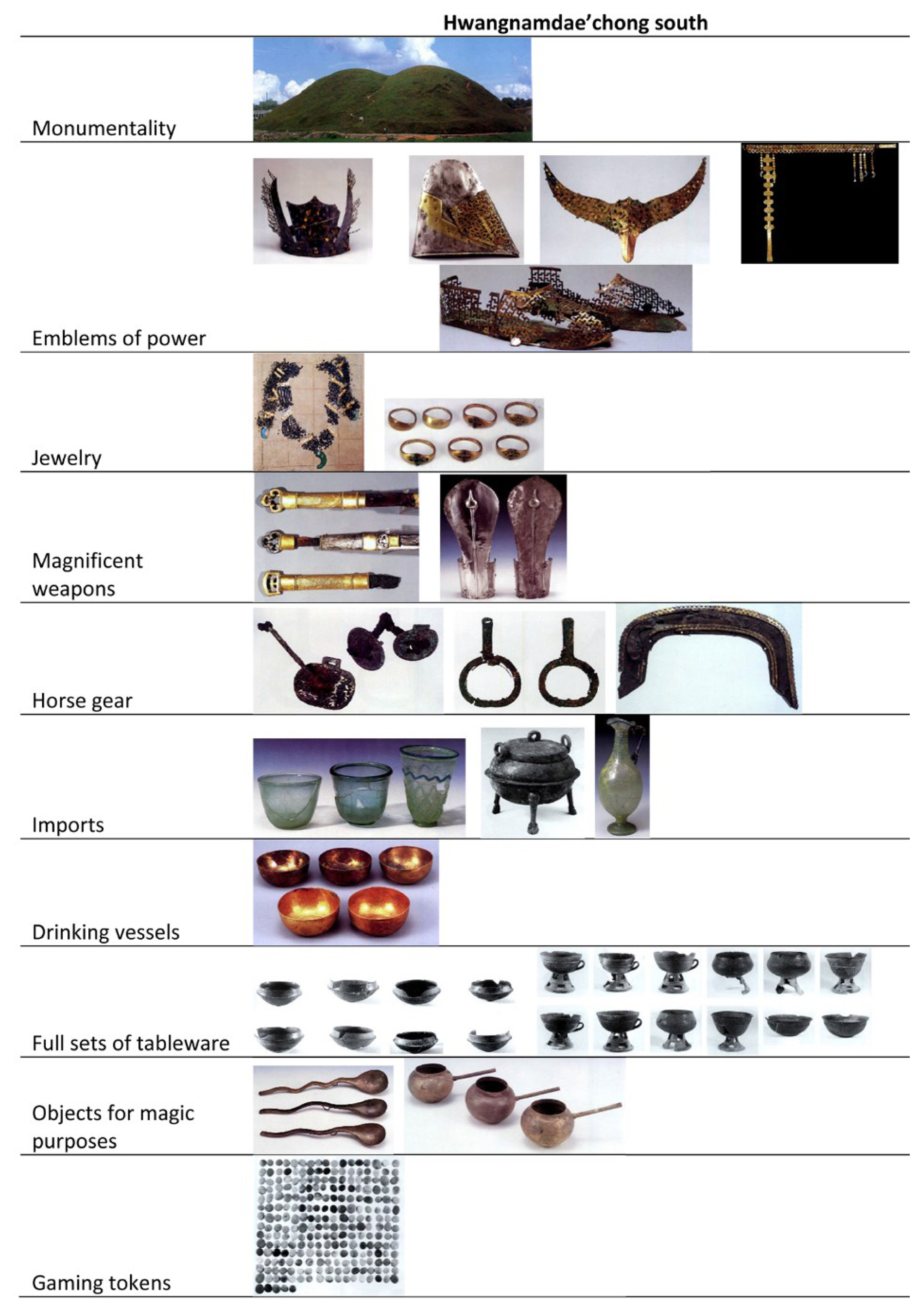

The deceased was placed inside a wooden coffin in a supine position in the middle of a square-shaped or rectangular chamber. The chamber size can be of considerable difference ranging between 250 x 80 cm and 660 x 430 cm.20, Expectable variations in the placement of arms and legs etc. are not ascertainable anymore, since bones have been preserved in the acidic soil of the Korean Peninsula only at a few sites. The deceased were equipped with personal adornment and weapons (fig. 4). Commonly, a larger amount of grave goods including elements of a horse harness, tools and vessels made of metal or pottery were stored in a chest located at the head or foot of the deceased.21 Often, older graves have an additional square- or rectangular-shaped storage chamber next to their short or long side.

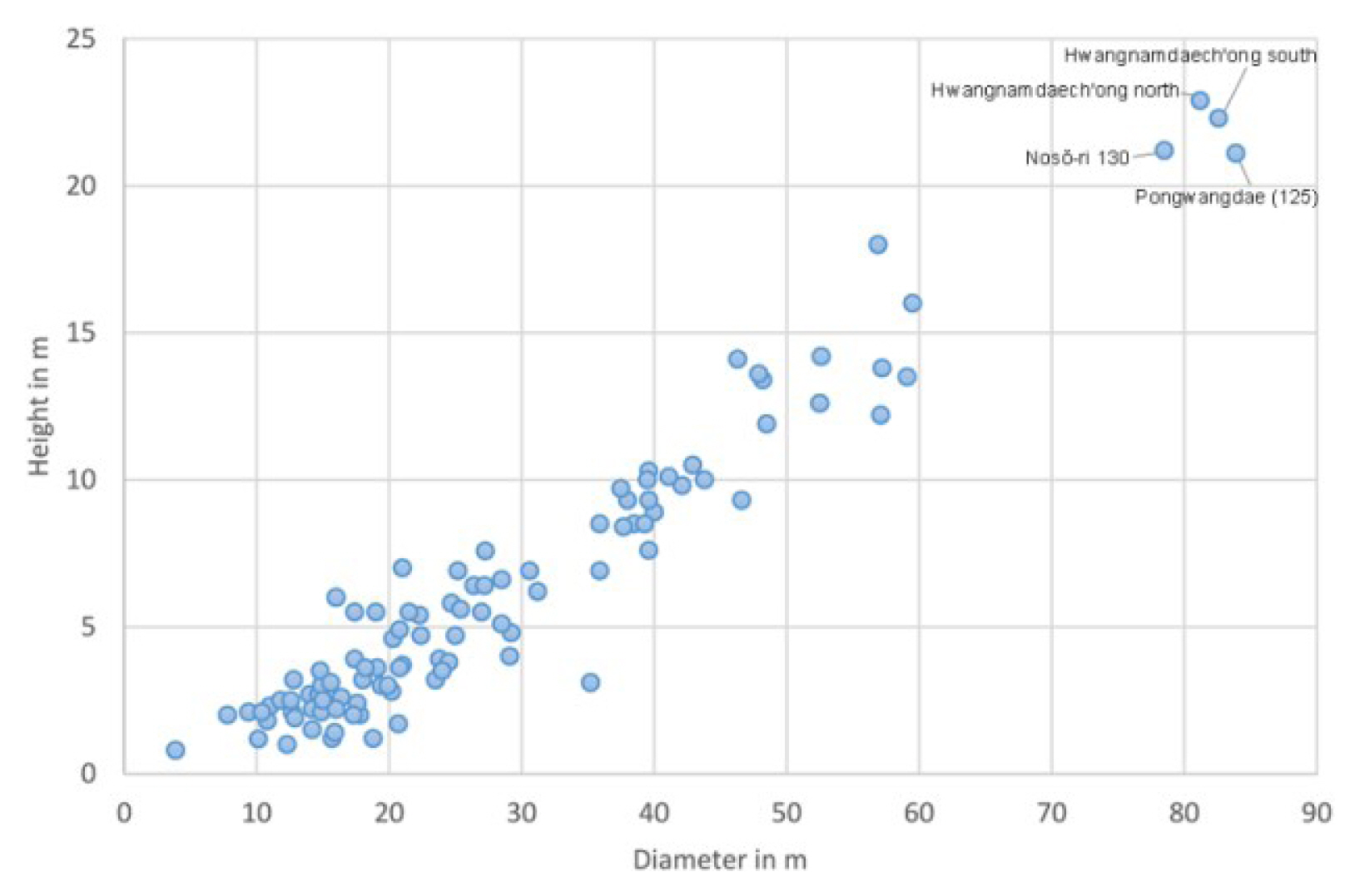

Particularly interesting for the following discussion is the fact that a few stone mound tombs in Kyŏngju, including the famous northern and southern mounds excavated at the Great Tomb of Hwangnam (Hwangnam taech’ong), are distinguished from the other mounds through their extreme measurements (fig. 5). These burials are truly monumental, although this term might be also applicable to other, less outstanding graves.

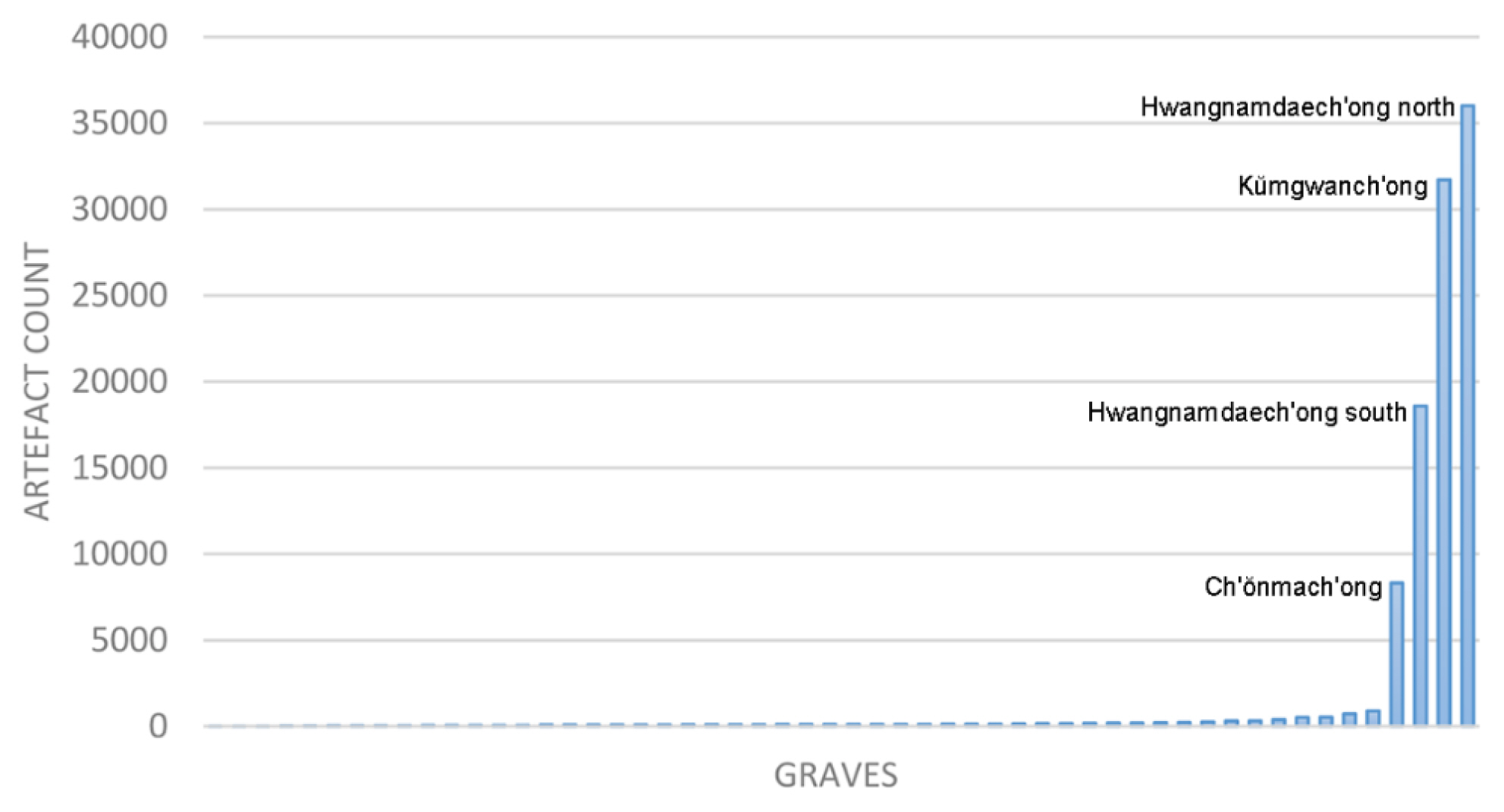

The variation in the size of the stone mound tombs indicates a significant fact, that is also proven by other instances, namely that these burials are not a homogenous group. Several examinations of the grave goods and their combinations have shown a variety of patterns23, ranging from very modest to extremely lavish equipment (fig. 6).24, It is not very surprising that there is apparently a correlation between the size of the tombs and the amount, wealth, and diversity of their grave goods.25, Again, the excavated monumental graves Hwangnam taech’ong north and south turn out to be the most exceptional. In the existing artefact-based rankings of the excavated stone mound tombs, the monumental graves are usually merged in one group with other wealthy burials,26, but the obvious gap in the number of artefacts highlights the special character of the monumental examples (fig. 6).

Examinations of particular, gender-related grave goods such as the earrings in combination with the rarely preserved human remains, have proven that both genders were interred as main occupants in the stone mound tombs.28, Considering that people were also buried in other grave types in the cemetery north of Wŏlsŏng at that time, it is assumable that the stone mound tombs were constructed for a particular fraction of the society, which was, however, apparently not exclusively defined by gender, social status or other aspects that are commonly derived from the mortuary remains. Nevertheless, time is a factor that seems to have had a certain influence on the construction and equipment of the graves. The dating of the burials rests mainly on the chronological development of the pottery and other artefact groups such as stirrups or earrings.29, Stratigraphic observations of overlapping graves play an important role as well. Whilst the relative position of particular burials is not so much diverging between the schemes of different authors, the absolute dates given for one and the same burial can vary by up to more than fifty years.30, Radiocarbon dates from Hwangnam taech’ong and Ch’ŏnmach’ong (Heavenly Horse Tomb) are not precise enough to ascribe the burials to an individual known from the historical sources. The samples from the southern burial of Hwangnam taech’ong date, for instance, the grave’s construction between 420 and 520.31, In the best case, this would eliminate only one of the known maripkans from the list of possible grave occupants. Generally, the enticing and quite often practiced task to link a specific tomb to one of the six maripkans known from the historical sources is at the current stage of research less likely to provide any reliable results.32, This is even more obvious by the fact that only a fraction of the graves in Kyŏngju have been excavated so far and none of them has produced a clear indicator of the identity of its occupant.33

For the following discussion, it is important to emphasize that the monumental burials of Hwangnam taech’ong north and south are considered to be earlier examples of the stone mound tombs.34, Only the rather modestly equipped burials of the two smaller mounds Hwangnam 109 and 110 are thought to be older.35, Both mounds belong to a grave cluster that is dominated by the unexcavated tumulus 106, also known as the grave of Mich’u Isagŭm, the first ruler set by the Kim Clan. The ascription of this tomb to Mich’u is, however, not only unproven but also quite unlikely considering his traditional reigning dates (r. 262–284). As observable in the case of the succeeding mounds Hwangnam taech’ong south, north and Ch’ŏnmach’ong, the architecture of the grave chamber of the older burials is characterized by higher complexity36 and it seems that the size of the mounds decreased over time.

The stone mound tombs that are of main interest for the present study are all distributed north of Wŏlsŏng, in the adjacent city areas of Nosŏ-ri, Nodong-ri, Hwango-ri, Hwangnam-ri and Inwang-dong (fig. 7). Other mounded tombs, among which are also the last resting places of Silla’s later kings and queens, occur in closer or wider distance from the city center. It has been presumed that particular grave clusters were the burial grounds of Silla’s influential clans known from the historical scriptures.37, The biggest mounds of the maripkan period are located in the cemetery north of Wŏlsŏng and since all of the known maripkans were members of the Kim Clan, the entire cemetery has been interpreted as their burial ground.38

Although the visible and by excavation discovered barrows in the cemetery north of Wŏlsŏng do certainly not represent the original distribution status, it is possible to recognize more or less distinct clusters including bigger and smaller mounds. Due to the fact that only a fraction of the graves have been excavated, the reasons for the clustering remain unclear. Most scholars interpret the clusters as the result of a successive chronological development.

Yong Sŏng Kim (Yong Seong Kim), for instance, proposes six stages (I–VI), which is not coincidentally the number of the known maripkans (fig. 8C). The problem with this approach is the chronological equation of the few unearthed burials with all the unexcavated graves within a cluster. Another, albeit similar interpretation by Kwangyŏl Pak (Kwangyoul Park) ascribes each of the bigger tumuli to one of the six maripkans and groups these graves together with selected smaller mounds in the vicinity (fig. 8B).40, Pyŏngyŏn Ch’oe’s (Byunghyun Choi) suggestion of the cemetery’s development (fig. 8A) is based on the most recent data gathered by excavations in the Tchoksaem district, located next to the big mounds of Hwangnam-ri. Here, on a small scale, the growth of grave clusters beginning with a bigger founder grave that is successively surrounded by smaller satellite burials is well documented.41, Synchronous, nuclei-based distribution patterns that occur in different sectors of a cemetery have been observed by Sŏngju Lee (Sung-joo Lee) and Sonch’ŏl Lee (Sohn Chul Lee) with help of a GIS-based analysis of larger Silla and Kaya cemeteries.42, Based on these results, it can be argued that the grave clusters in the cemetery north of Wŏlsŏng did not all emerge one after another, as assumed by most scholars, but partly at the same time. An examination of the mitochondrial DNA (mDNA) gathered from bones of tumuli distributed over the two neighboring sites at Imdang-dong and Choyŏng-dong in Kyŏngsan which offer better conditions for the preservation of human remains, have revealed a high matrilineal diversity among the individuals buried in clusters.43 Therefore, it seems that the burial owners were not close family members, which is a result that needs to be taken into consideration for the interpretation of other Silla burial grounds as well.

Ostentatious Graves

“Throughout world history, colossal royal tombs have served as both public monuments and emblems of the sovereign state. The emergence of a great ruler thus can be inferred from the size of his tomb.”44

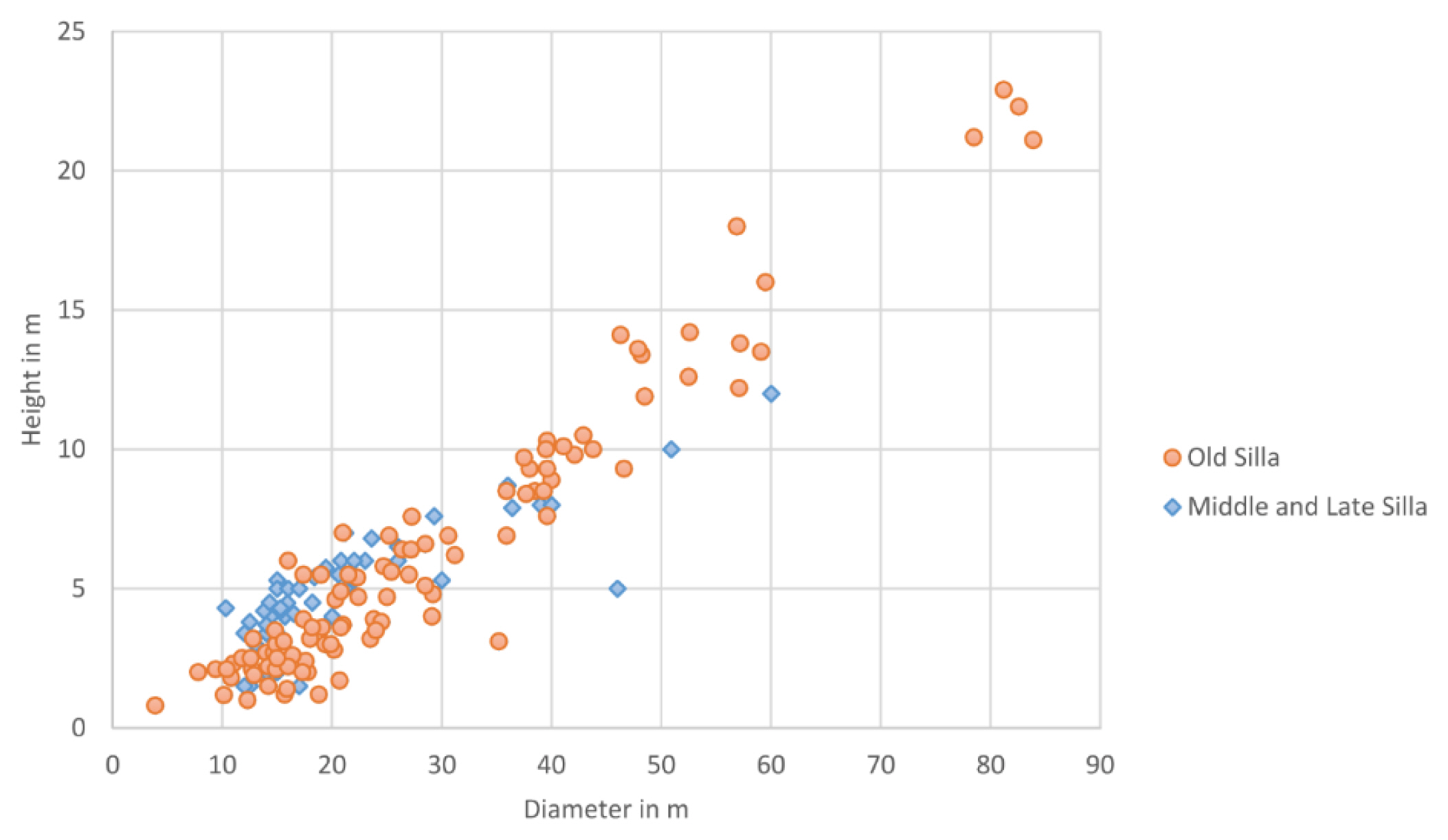

The statement above, given by Sun-Sŏp Ham (Soon-Seop Ham) on the stone mound tombs, sums up a common and seemingly plausible view-point on monumental graves in general. In the case of the mounded tombs in Kyŏngju, there cannot be any doubt that they served as public monuments and as reference points for the collective memory of the community. Moreover, it has been proven through cross-cultural anthropological research that the cost expenditure of the grave construction is indeed in most cultures connected to the social position of the deceased.45, In this sense, it seems to be logical that the memory of a successful and powerful ruler was honored with a bigger burial. This notion is, however, not tenable in light of the above-mentioned observation that the size and complexity of the stone mound tombs were seemingly influenced by the factor of time. This becomes apparent if the more or less clearly identifiable royal tombs from the middle and late stage of Silla are included in the comparison of the mounds’ measurements (fig. 9). Given that the later tombs follow a different construction principle – they consist of a stone chamber that is accessible through a corridor or dromos – their size is significantly smaller than that of the big and monumental mounds from the maripkan period. Thus, if the importance of the buried individual is mainly determined by the size of the tomb, we have to assume that the individuals interred in the earlier maripkan period were more important or successful than their direct successors and even any other ruler in the century-old history of Silla. This was certainly not the case and there must be other reasons that explain the decrease of the grave size in the course of time.

In the following section, it will be argued that particularly the monumental stone mound tombs are the result of political and social changes during the maripkan period. Discussing the graves from this angle is by no means new, although the main focus of research has been on the social ranking, chronology, and origin of the burials. Gina Barnes, for example, interprets the stone mound tombs as indicators for the process of state formation.46, Tuch’ŏl Kim (Doo Chul Kim) understands them as an expression of Silla’s political independence,47, whilst Chaewŏn Ok (Jaewon Ok) offers a deeper socio-political analysis. He interprets the fact that bigger and lavishly equipped graves occur at the beginning of the tombs’ development as an attempt by the ruling Kim Clan to establish and maintain its power over the polity through ostentation in the mortuary rituals, by equally restricting this praxis for other clans.48

As Ham has implied in his statement quoted above, graves of monumental size with lavish equipment are indeed a global phenomenon. They are, however, neither ‘emblems of the sovereign state’ nor do they necessarily mark the ‘emergence of a great ruler’ as has been demonstrated by the German archaeologist Georg Kossack.49, In a cross-cultural study that comprises a range of outstanding burials in Europe, Northern Africa and Western Asia from prehistory up to medieval times, he termed burials of monumental size with lavish equipment as ‘ostentatious graves.’ He observed that neither kings and queens nor members of the royal family were always buried in ostentatious graves.50, Often, monarchs appear to be treated like the members of other influential families or the elite of their country.51, He also noticed that ostentatious graves are in most cases a chronologically limited phenomenon.52

Although the definition of what an ostentatious grave might be for a particular community differs within the context of each culture or civilization, Kossack recognized a number of features that occur frequently in those burials in varying combinations, distinguishing ostentatious graves from, for instance, wealthier burials of a community. According to Kossack, ostentatious graves are often characterized by their monumental size. They usually have a grave chamber that is at times exceptionally decorated and the body of the grave owner might be treated differently from the norm.53, The grave equipment might contain items for an exclusive lifestyle, including products of high-quality craftsmanship and imports from foreign lands. If weapons occur, they are made in a magnificent way.54, Common is the equipment with horse gear or even with the horses themselves. Gaming boards, music instruments, precious clothes, jewelry, cleansing equipment, portions of meat, beverages and accompanying drinking vessels are often observable as well.55, Ostentatious graves frequently contain tableware in full sets to supply, for instance, an eternal banquet. Furthermore, these graves include objects for magical purposes and emblems of power.56, Although not all of the mentioned categories are observable in the stone mound tombs57, and particular aspects such as the treatment of the body cannot be ascertained, it is clear that the monumental graves, which are also the most lavishly equipped (compare fig. 5–6), can be defined as ‘ostentatious graves’ (fig. 10).

Kossack58, interpreted these burials as “an expression of culture change in progress.”59, In his opinion, the occurrence of these graves is mainly the result of a stress-situation caused by the encounter of a local community at the cultural periphery of a civilization with exactly this advanced polity or with other foreign phenomena.60, The foreign counterpart is in this constellation seen as superior, which leads – depending on the character of the local elite’s claim to power – to a challenge of the authority of the ruling group within their community. In the course of the contact situation, the local elite aims to emulate the conspicuous consumption and lifestyle of their foreign counterpart, resulting, amongst others, in the adoption of elements of the foreign culture.61 This is, of course, only possible in the scale of the economic potential of the local elite and it might happen that not all of the adopted elements are fully understood or implemented in the originally intended way. The latter is also explainable through conscious alterations in order to adjust the new cultural elements to the traditional local culture.

Ostentatious graves have at least two functions. First of all, they can be understood as a strategy of the local elite to demonstrate their power and wealth to the foreign and more advanced counterpart.62, They are expressions of an attempt to communicate and operate on an equal level in a disparate power-relationship. Secondly, they are a demonstration of power towards the local communities,63 which have to cope with the realization that there are more powerful political entities outside their own realm, a fact that is likely to question the authority and ability of their local rulers.

Kyŏngju’s monumental tumuli interpreted as ‘ostentatious graves’

In the case of the stone mound tombs in Kyŏngju, two protagonists in the closer and wider distance of Silla come into consideration as powerful counterparts that might have triggered the construction of the monumental graves. The first one is imperial China, which experienced uncertain times during the maripkan period. Contact between Silla and a Chinese dynasty is – if accepted as trustworthy – reported for the year 381. Naemul, the first maripkan according to the Samguk yusa, is said to have sent a tribute mission to the Former Qin (前秦) ruler (Samguk Sagi III. Isagŭm Naemul). Beyond this entry, the exact nature of the relationship between Silla and Former Qin, which only lasted until 394, remains unclear.64, The same is true for the following dynasties. Apparently more direct and intense was the contact with the second protagonist that has to be mentioned: Koguryŏ. Under the famous king Kwanggaet’o (r. 391–413) the territory of the kingdom increased dramatically, amongst others, deep into the Korean Peninsula.65, At this time Koguryŏ became an empire that was on par with the imperial Chinese dynasties. The famous stele of King Kwanggaet’o that includes short but significant remarks about Silla is a valuable primary source of that period. Two entries dating to the years 399 and 400 report that Silla had to rely on Koguryŏ for military support and, thus, submitted to its northern neighbor.66, Although the Samguk sagi and Samguk yusa do not mention this significant event at all, the implied and undoubtedly existent power imbalance between Silla and Koguryŏ is also traceable in these two sources. According to the Samguk sagi, in the year 392, Silla’s ruler Naemul sent Silsŏng, who would become the next ruler, as a hostage to Koguryŏ (Samguk sagi III. Isagŭm Naemul). Hostage diplomacy was apparently a common practice at that time,67, in the case of Silsŏng the reason for sending him, as the Samguk sagi states, was that Naemul considered Koguryŏ to be powerful (Samguk sagi III. Isagŭm Naemul). Further incidents suggest that Koguryŏ interfered in internal matters of Silla and from the middle of the fifth century a significant deterioration of the relationship between both polities is observable.68 It seems that the pressure on Silla caused by Koguryŏ, first as a protector and later as an opponent, was extremely high.

Evidence for the influence of Koguryŏ on Silla is not only ascertainable through the historical sources, but also recognizable in the archaeological remains. Metal vessels and other artefacts produced in Koguryŏ prove the by no means surprising exchange of goods, but also the seemingly strong impact of Koguryŏ’s style on artefacts used by the elite (Kang 2003, 24–25).69, Although most of the celebrated golden and gilded crowns of Silla are characterized by a typical style, they show similarities to the few known examples from Koguryŏ.70, Another status indicator of Silla, the golden earrings, is akin in regard of style to known examples from the northern neighbor.71, Metal objects with elaborate openwork ornamentation such as the famous golden belts, saddles and other elements of the horse harness have similar counterparts in Koguryŏ as well.72 All these artefacts were used by the upper stratum of the society and they are evidence for the emulation of Koguryŏ’s elite lifestyle by Silla’s ruling groups.

Another indicator of the cultural predominance of Koguryŏ could be the stone mound tombs themselves. As has been outlined in recent overviews on that matter by Ch’oe and Shim,73, scholarly opinions are divided over the question whether the wooden chamber tombs within a stone mound are a foreign or local burial type. One of the strongest proponents for a foreign origin of the stone mound tombs is Pyŏnghyŏng Ch’oe (Byunghyung Choi), who recognizes the closest counterparts to the tumuli in Kyŏngju in the kurgans of the Siberian steppe.74, Even though there is indeed a number of similarities between the mounded tombs in both areas, the major objection to his theory is clearly the spatial and chronological distance of the kurgans to the Silla tombs. Other authors, who advocate for a foreign origin, name Koguryŏ as the most plausible source of influence.75, This is because Koguryŏ had a long tradition in constructing tombs with a stone mound, some of them in monumental size, in its earlier phase as the center of the kingdom was located in Ji’an at the Yalu River.76, These tombs were entirely constructed of stones and have the shape of a step pyramid. This resembles to some degree the shape of the stone mounds in bigger tombs of Kyŏngju such as Hwangnam taech’ong (Great Tomb of Hwangnam), Ch’ŏnmach’ong (Heavenly Horse Tomb) and Kŭmgwanch’ong (Gold Crown Tomb). Nevertheless, the construction of the stone mound is not identical and the usage of wooden grave chambers is attested for the Yŏngnam region long before the Three Kingdoms period.77 Therefore, it seems to be more plausible, that the new elements, namely the stone mound plus the earthen mantle, are additions to the already existing element of the wooden grave chamber. All mentioned indicators from the historical and archaeological sources combined seem to suggest that Koguryŏ could have been the powerful and advanced counterpart that triggered the construction of the ostentatious graves in Kyŏngju.

Besides pressure from the outside, it is assumable that the elite members of the Silla polity stood in fierce competition with each other during the maripkan period. As has been mentioned earlier, the maripkan was – according to the meaning of the title – an individual from a high-ranking group of equals, who seems to have appointed the next ruler from their ranks. The historical sources do not explicitly report about rivalries between the leading families or clans of Silla. However, the story of Silsŏng maripkan provides a glimpse into these matters. As mentioned above, Silsŏng was sent to Koguryŏ as a hostage by Naemul maripkan. After becoming the ruler he sought revenge and aimed to kill Naemul’s son, Nulji, with the help of troops from Koguryŏ as the Samguk yusa reports (Samguk yusa I.25). In an unexpected move, the soldiers did, however, not kill Nulji, but turned instead against Silsŏng. It has been argued, that this story is a reflection of the power struggle between the Kim and the influential Sŏk Clan because Silsŏng’s mother was a Sŏk.78, It seems that although all known maripkans came from the Kim Clan, other influential families of the polity such as the Pak and Sŏk also attempted to claim the rule for themselves. It might be even possible that rivalries existed between different groups within the clans. In any case, both sides, the ruling clan and its rivals, might have had a reason to engage in the construction and equipment of ostentatious graves. From the perspective of the leading group, the time of the ruler’s death is an extremely dangerous period full of tension and more or less open power struggles. One of several measures to maintain and re-legitimate the claim to authority by the ruling clan was a lavish funeral ceremony and the accompanying rituals.79 Contrariwise, the performance of lavish mortuary rituals for a deceased member must have been a welcome opportunity for the rivaling groups to demonstrate power and wealth to the community of the capital and the entire polity.

Discussion and Conclusion

Approaching the wooden chamber tombs within a stone mound and particularly their monumental examples through G. Kossack’s concept of ‘ostentatious graves’ has a number of consequences that challenge commonly accepted interpretations. As has been discussed in the previous segment, there are a number of arguments to assume that the encounter with Koguryŏ and its seemingly strong influence on Silla triggered the construction of the big and monumental stone mound tombs. Although there is no doubt that the graves do represent the economic potential of Silla’s elite through the ostentation of wealth and the use of labor in the maripkan period, they are not – as commonly perceived – an expression of independence and political strength. Actually, the opposite is true. The construction of these graves is an indicator for a high degree of uncertainty and a position of weakness of the local elite on the international political stage as well as on the inner polity level. The monumental graves are before all an exaggerated claim to power and authority, an attempt to legitimate the elevated position of the elite, which is only necessary if this position is being contested. Thus, the tombs from the middle and later stage of Silla, as the kingship was firmly established, become more ‘modest’ in size and equipment. This assumption has, of course, a number of repercussions on the interpretation of the cemetery north of Wolsŏng in general and on some of the graves in particular. According to the insights of the ‘ostentatious grave’ concept, it is more likely that the biggest mounds such as Hwangnam taech’ong or the unexcavated graves Ponghwangtae and Nosŏdong 130 were all constructed at the beginning of the maripkan period as the stone mound tombs came into being. Therefore, the common development schemes that assume all the barrows in the northwestern area to be later than those in the southwest (fig. 8) have to be reconsidered.80, The widely shared perception that the big and monumental graves were the last resting places of the maripkans has to be questioned as well. Although this is a plausible interpretation, there are – at the current state of research – no further arguments besides the graves’ measurements that would support this idea. The monumental size and the lavish equipment of the biggest wooden chamber tombs within a stone mound were not merely means to demonstrate the status of the deceased, but to a large extent prove the economic and political power of the group which constructed the grave. Thus, the opportunity for the ostentation of wealth was, for instance, also given in the course of a funeral for a member of the ruling family besides the actual ruler. This suggestion may cause disapproval first, but it is supported by the burial of Hwangnam taech’ong north. According to the current interpretation of the grave, the occupant was the consort of the male, who was buried in the southern mound. Assuming the latter was indeed one of the maripkans, this would mean that monumental and lavishly equipped burials were also constructed for individuals, who were not the actual rulers of the polity.81

Furthermore, there is no reason to believe that the cemetery north of Wolsŏng was exclusively used by the Kim Clan. As mentioned above, it is quite likely that the observable grave clusters are not the result of a strictly diachronic development. Thus, it is at least possible that some of the bigger tombs were constructed by the members of rival families in order to challenge the position of the ruling group and to demonstrate their own claim to power within the community.

In the same way as the size of the monumental graves has to be understood as an exception from the norm, so has to be their equipment. This, however, has consequences for the interpretation of the grave goods as indicators of the social ranking of Silla’s society. Although there cannot be any doubt that particular artefact patterns are observable in the equipment of the burials, it remains difficult to identify, for instance, the maripkans through their grave goods. Supposed ‘royal’ regalia or high-status markers such as the crowns, belts, and shoes are by no means limited to the bigger graves or to one burial cluster (fig. 11). Generally, there are no clear indicators that the access to prestige goods and status items was restricted as in later times through the rigid rules of the bone-rank system.82, The approach to focus more on the items that were directly worn by the deceased, as carried out by Hŭichun Lee (Heejoon Lee), is certainly a step in the right direction.83

It is obvious that the suggested interpretation of the archaeological remains and the objections towards a number of established explanations do enormously complicate things. The prospects to identify the owner of the excavated graves become much lower for the time being. The current uncertainties of the chronological system combined with the fact that only a fraction of the existing graves have been excavated, renders it, additionally, difficult to align the historical with the archaeological sources. However, this is also an opportunity to change the perspective on the mounded tombs in Kyŏngju. Their value lies primarily in their potential to provide information for reconstructing structural historical developments in Silla and East Asia, instead of confirming individual biographies recorded in the historical sources.

Notes

See for instance Richard Pearson et al., “Social Ranking in the Kingdom of Old Silla, Korea: Analysis of Burials,” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 8, no.1 (March 1989): 1–50. Choi Suhyung(Suhyŏng), “Kyŏngjujiyŏk chŏksŏng-mokkwangmyoŭi wigyegujo kŏmt’o (The research about the class structure of the wooden chamber tombs with a stone mound in Gyeong-Ju region),” Chun-ganggogoyŏn’gu 12 (April 2013): 62–94. Choi Byunghyun, “Silla chŏn’gi kyŏngju wŏlsŏngbukkobun’gunŭi kyech’ŭngsŏnggwa poksikkun (Social Stratification and the Personal Ornament Assemblages of the Wolseong North Burial Ground of Gyeongju in the Early Silla Phase),” Han’gukkogohakpo 104 (September 2017a): 78–123.

Jonathan W. Best, A History of the Early Korean Kingdom of Paekche (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2006), 6–7. Jonathan W. Best, “Problems in the Samguk Sagi’s Representation of Early Silla History,” Seoul Journal of Korean Studies 29, no. 1 (June 2016): 1–2.

Choo Bodon, “Yŏngillaengsurisillabie taehan kich’ojŏk kŏmt’o (Basic Review on the Silla stele of Yŏngil Naengsu-ri),” Silla munhwa 6 (December 1989): 53–84.

Richard D. McBride II, “Introduction” in State and Society in Middle and Late Silla, ed. Richard D. McBride II (Cambridge, MA: Korea Institute, Harvard University, 2010), 4–5.

The citation of the sources refers not to a particular edition, but to the general text passage. For consultations of the original text refer to: Pusik Kim (金富軾), Samguk sagi (三國史記), critical apparatus by 鄭求福 (Chŏng Kubok), 盧重國 (No Chungguk), 申東河 (Sin Tongha), 金泰植 (Kim T’aesik), and 權悳永 (Kwŏn Tŏgyŏng). 國史叢書 Kuksa Ch’ongsŏ (National History Series) 96–1, (Seoul: 韓國精神文化硏究院 (Han’guk Chŏngsin Munhwa Yŏn’guwŏn), 1996). As basis for the English translation the following works were used: Pusik Kim, The Silla Annals of the Samguk Sagi, trans. Edward J. Schultz and Hugh H.W. Kang (Seongnam: The Academy of Korean Studies Press, 2012). Ilyon, Samguk Yusa, trans. Tae-Hung Ha and Grafton K. Mintz (Seoul: Yonsei University Press, 2007).

Ham Soonseop(Sunsŏp), “Gold Culture of the Silla Kingdom and Maripgan,” in Silla. Korea’s Golden Kingdom, ed. Soyoung Lee and Denise Patry Leidy (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013), 32.

Ham, “Gold Culture of the Silla Kingdom and Maripgan,” 32. It is noteworthy that the Samguk sagi and Samguk yusa show a disparity regarding the first occurrence of the title maripkan. According to the Samguk yusa the first maripkan was, as mentioned, Naemul, but the Samguk sagi states that Naemul’s son Nulchi (r. 417–458) was the first to carry this title.

McBride, “Introduction,” 6.

As epigraphic finds such as the stele of Naengsu-ri west of P’ohang (Choo Bodon, “Yŏngillaengsurisillabie taehan kich’ojŏk kŏmt’o (Basic Review on the Silla stele of Yŏngil Naengsu-ri),” Sillamunhwa 6 (December 1989): 53–84) or the inscription on two swords found in the Gold Crown Tomb (Kŭmgwanch’ong) in Kyŏngju (Kim Jaehong, “‘Isajiwang’myŏng taedowa kŭmgwanch’ongŭi chuin’gong (The Identity of the Owner of the Sword with the ‘Yisajiwang’ Inscription from Ge-umgwanchong Tomb).” Kogohakchi 20 (December 2014): 117–146) demonstrate, the title wang did already exist in Silla at the maripkan period. It seems, however, that the maripkan had, as the title implies, higher authority.

Lee Geunjik(Kŭnjik), “The Development of Royal Tombs in Silla,” International Journal of Korean History 14 (August 2009): 93.

E.g. Gina Lee Barnes, State Formation in Korea: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives, (Richmond: Curzon Press, 2001), 3. Ham, “Gold Culture of the Silla Kingdom and Maripgan,” 33.

Ham, “Gold Culture of the Silla Kingdom and Maripgan,” 38–41. Sarah Milledge Nelson, Gyeongju. The Capital of Golden Silla (London and New York: Routledge, 2017), 29.

Lee, “The Development of Royal Tombs in Silla,” 92–93.

For the sake of simplicity the term ‘stone mound tombs’ will be used for this kind of graves in the present article.

Kim Yongseong(Yongsŏng), “Chŏksŏngmokkwangmyoŭi saeroun ihae (New Understanding of Wooden Chamber Tombs with Stone Mound),” Kogohak yŏn’gu konggaegangjwa 6 (Yeongnam Munhajae Yeonguwon, 2006): table 2, figure 7.

After Kim 2006, fig. 7; table 3.

See Gina Lee Barnes, “The Emergence and Expansion of Silla from an Archaeological Perspective,” Korean Studies 28 (July 2004): 26.

Byunghyun Choi, Silla kobun yŏn’gu (Silla Tumulus Research) (Seoul: Iljisa, 1992), 110.

After Shim Hyuouncheol(Hyŏnch’ŏl), “Silla chŏksŏngmokkwangmyoŭi kujowa ch’uk-chogongjŏng (The Structure and Construction Process of the Silla Wooden Chamber Tomb with Stone Mound),” Han’gukkogohakpo 88 (September 2013): fig. 2.

Shim Hyuouncheol(Hyŏnch’ŏl), “Silla chŏksŏngmokkwangmyoŭi kujowa ch’uk-chogongjŏng (The Structure and Construction Process of the Silla Wooden Chamber Tomb with Stone Mound),” Han’gukkogohakpo 88 (September 2013): table 7.

Choi, Silla kobun yŏn’gu, 188.

Basis after GGMY, Sillagobun kich’ohaksuljosayŏn’gu III (Silla mounded tomb academic research report), (Gyeongju: Kungnipkyŏngjumunhwajaeyŏn’guso, 2007), 193, 212.

See note 1 above.

Choi, “Kyŏngjujiyŏk chŏksŏngmokkwangmyoŭi wigyegujo kŏmt’o,” table 4.

Choi, table 4.

Choi, table 4. Choi, “Silla chŏn’gi kyŏngju wŏlsŏngbukkobun’gunŭi kyech’ŭngsŏnggwa poksikkun,”.

The numbers are approximated values based on the data given in GGMY, Sillagobun kich’ohaksuljosayŏn’gu III.

Choi, Silla kobun yŏn’gu, 273.

Choi Byounghyun, “5segi silla chŏn’giyangsikt’ogiŭi p’yŏnnyŏn’gwa sillat’ogi chŏn’gaeŭi chŏngch’ijŏk hamŭi (Chronology of Fifth Century Silla Pottery and Its Implications on the Political Development of Silla),” Kogohak 13, no.3 (August 2014a): 159–229. Choi Byunghyun, “Ch’ogi tŭ ngjaŭi paljŏn (The Development of Early Stirrups in Ancient Northeast Asia),” Chunganggogoyŏn’gu 14 (June 2014b): 2–57.

See e.g. Kim Yongseong(Yongsŏng), Sillawangdoŭi koch’onggwa kŭ chubyŏn (The graves of the old Silla kingdom and its surroundings) (Seoul: Hagyŏnmunhwasa, 2009), table 3. Kim Doo Chul, “Hwangnamdaech’ong nambun’gwa sillagobunŭi p’yŏnnyŏn (Hwangnamdaech’ong southern tomb and Silla tomb chronology),” Han’gukkogohakpo 80 (September 2011): table 1.

Kim, Sillawangdoŭi koch’onggwa kŭ chubyŏn, 83.

Lee Changhee, “Pangsasŏngt’ansoyŏndaero pon hwangnamdaech’ong nambun’gwa suhyegiŭi siryŏndae. Pangsasŏngt’ansoyŏndaeŭi chŏgyongbangbŏpkwa t’adangsŏng chaego (The calendar date of Hwangnamdaech’ong Nambun & Sueki. Application method and examination of feasibility),” Komunhwa 79 (June 2012): 57–58.

The famous Kŭmgwanch’ong (Gold Crown Tomb) in Kyŏngju contained two swords that carried an inscription with the name and title King Isaji (尒斯智王). Besides the fact that King Isaji is not mentioned in the available written sources, it is not necessarily compelling to reason that the name is referring to the actual grave owner (Kim, “‘Isajiwang’myŏng taedowa kŭmgwanch’ongŭi chuin’gong,” 143).

Kim, Sillawangdoŭi koch’onggwa kŭ chubyŏn, table 3. Kim, “Hwangnamdaech’ong nambun’gwa sillagobunŭi p’yŏnnyŏn,” table 1.

Regarding the dating of the burials, recently made remarks by Tuch’ŏl Kim (Doo Chul Kim) have to be taken into consideration. In Korean archaeological research the dating of find contexts has been mainly based on single features of particular artefact groups without the necessary emphasis on the entire artefact spectrum. Kim also points to the issue that larger, more lavishly equipped burials in the center of a polity might include more progressive and modern elements than contemporary burials in the periphery (Doo Chul, “P’yŏnnyŏn pun’giesŏŭi hyŏngsikhakchŏk chŏpkŭn saryee taehan pip’anjŏk kŏmt’o (Critical review on instances of typological approach in periodization and chronology),” Kogogwangjang 17 (December 2015): 1–29).

Choi Byunghyun, “Silla chŏksŏngmokkwakpun kiwŏn yŏn’guŭi pangyang (Research Directions on the Origins of the Silla Wooden Chamber Tomb with Stone Mound),” Chunganggogoyŏn’gu 21 (December 2016): 137.

Barnes, State Formation in Korea, 214–216.

Barnes, table 8.4.

A: after Choi, “Silla chŏn’gi chŏksŏngmokkwakpunŭi myohyŏnggwa chiptanbokhammyogunŭi sŏnggyŏk,” fig. 9; B: after Park, “Silla chŏksŏngmokkwakpunŭi yŏn’guwa kŭmgwanch’ong,” fig. 6; C: after Kim, Sillawangdoŭi koch’onggwa kŭ chubyŏn, fig. 2–8.

Park Kwangyoul, “Silla chŏksŏngmokkwakpunŭi yŏn’guwa kŭmgwanch’ong (Research on the Silla Stone Chamber Tomb with Corridor Entrance and Geumgwanchong Tomb),” Kogohakchi 20 (December 2014): 53–77.

Choi Byounghyun, “Silla chŏn’gi chŏksŏngmokkwakpunŭi myohyŏnggwa chiptanbokhammyogunŭi sŏnggyŏk (The Distributional Patterns of Silla Burial Grounds and the Character of Outer Coffin Tombs in Jjoksaem Site, Gyeongju),” Munhwajae 50 no. 4 (December 2017b): 190–193.

Lee Sungjoo and Sohn Chul, “GISrŭl iyonghan silla kobun’gun kongganjojigŭi punsŏk (The GIS Analysis of the Spatial Organization in Silla Cemeteries),” Han’gukkogohakpo 55 (April 2005): 77–103.

Lee et al., “Kyŏngsan imdang yujŏk koch’onggun p’ijangja chiptanŭi sŏnggyŏk yŏn’gu. ch’ult’o in’gorŭi mit’ok’ondŭria DNA punsŏgŭl chungsimŭro (The Relations of the Dead: Identifying the relationship of individuals buried at Imdang, Gyeongsan, through the analysis of mitochondrial DNA from human skeletal remains interred in large mounded tombs),” Han’gukkogohakpo 68 (September 2008): 128–155.

Ham, “Gold Culture of the Silla Kingdom and Maripgan,” 42.

Christopher Carr, “Mortuary Practices: Their Social, Philosophical-Religious, Circumstantial, and Physical Determinants,” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, Vol 2, no. 2 (June 1995): 180.

Barnes, State Formation in Korea, 221.

Kim, Sillawangdoŭi koch’onggwa kŭ chubyŏn, 81–82.

Ok Jaewon, “Silla chŏksŏngmokkwangmyoŭi choyŏng yangsanggwa kwŏllyŏk-kujoŭi pyŏndong (The Constructing process of wooden chamber tomb with a stone mound and the change of central power structure in Silla),” Yŏksawahyŏnsil 106 (December 2017): 145–185.

Georg Kossack, “Ostentatious Graves,” in Towards Translating the Past. Georg Kossack. Selected Studies in Archaeology, ed. Bernhard Hänsel and Anthony F. Harding (Rahden/Westf.: Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH, 1995), 13–37. The cited study was already published in 1974 in German, but republished in an English version in 1995.

Kossack, “Ostentatious Graves,” 15.

Kossack, 36.

Kossack, 36.

Kossack, 14.

Kossack, 14.

Kossack, 14.

Kossack, 14.

Compare Choi, “Kyŏngjujiyŏk chŏksŏngmokkwangmyoŭi wigyegujo kŏmt’o,” table 4.

Image from: Munhwajaeyŏn’guso, Hwangnamdaech’ong(Nambun) Palgulchosabogosŏ (Hwangnamdaech’ong(South Mound) Excavation Report) (Kyŏngju: Munhwajaeyŏn’guso, 1993).

Kossack, “Ostentatious Graves,” 36.

Kossack, 36.

Kossack, 33–34.

Kossack, 33–34.

Kossack, 36.

Ham, “Gold Culture of the Silla Kingdom and Maripgan,” 33.

Kang Hyunsook(Hyŏnsuk), “New Perspectives of Koguryŏ Archaeological Data,” in Early Korea 1. Reconsidering Early Korean History through Archaeology, ed. Mark E. Byington (Cambridge, MA: Korea Institute, Harvard University, 2008), 13.

Noh Taedon(T”aedon), “A Study of Koguryŏ Relations Recorded in the Silla Annals of the Samguk Sagi,” Korean Studies 28 (July 2004): 107–108.

Naemul sent also, as the Samguk yusa reports, his third son Mihae to Japan (Samguk yusa I.24). According to the source the Japanese ruler did not keep his promise to treat Naemul’s son as an envoy, but just held him as a hostage.

Noh, “A Study of Koguryŏ Relations,” 108–113.

Kang Hyunsook(Hyŏnsuk), “Silla kobunmisuresŏ poinŭn koguryŏ yŏnghyange taehayŏ (A Study on the Effect of Koguryŏ on Silla in the View of Tomb Culture),” Sillamunhwajehaksulbalp’yononmunjip 24 (February 2003): 15–16.

Particularly insightful is the bronze lidded bowl from tumulus Nosŏ-ri 140 also known as Houch’ong which carries an inscription on the bottom that celebrates King Kwanggaet’o. Since Houch’ong is commonly dated to the beginning of the sixth century (see e.g. Kim, Sillawangdoŭi koch’onggwa kŭ chubyŏn,” table 3) the bowl must have been in circulation for almost a century before it was stored in the grave (Park Kwangyoul, “Silla sŏbongch’onggwa houch’ongŭi chŏlda enyŏndaego (Silla Sŏbongch’ong’s and Houch’ong’s absolute dates),” Han’gukkogohakpo 41 (October 1999): 73–106).

Most of Koguryŏ’s tombs have been looted due to the easy accessibility of the grave chamber. Thus, a comparatively small amount of elite goods, which are usually transmitted through burial contexts, are known from the kingdom.

Kang, “Silla kobunmisuresŏ poinŭn koguryŏ yŏnghyange taehayŏ,” 16–17.

Kang, 21–23.

Choi, “Silla chŏksŏngmokkwakpun kiwŏn yŏn’guŭi pangyang,”. Shim, “Silla chŏksŏngmokkwangmyoŭi kujowa ch’ukchogongjŏng,” table 1.

Choi, Silla kobun yŏn’gu, 397–412.

Shim, “Silla chŏksŏngmokkwangmyoŭi kujowa ch’ukchogongjŏng,” table 1.

Kang, “New Perspectives of Koguryŏ Archaeological Data,” 25. Kim, Sillawangdoŭi koch’onggwa kŭ chubyŏn, 298–331.

Choi Suhyŏng,”Kyŏngjujiyŏk mokkwangmyoŭi pyŏnch’ŏn’gwajŏnggwa sŏnggyŏk kŏmt’o (A changing process and review on character of the wooden chamber tombs in Kyoungju region),” Yaoegogohak 21 (November 2014): 29–63.

Noh, “A Study of Koguryŏ Relations,” 108.

See also Glenn M. Schwartz, “Status, Ideology, and Memory in Third-Millenium Syria: “Royal” Tombs at Umm El-Marra,” in Performing Death. Social Analyses of Funerary Traditions in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean, ed. Nicola Laneri (Chicago: Oriental Institute, 2007), 47. Mike Parker Pearson, The Archaeology of Death and Burial (Stroud: The History Press, 2009), 87.

The main argument for this perception is apparently that the northwestern grave cluster which is composed of the burial mounds of Nosŏ-ri and Nodong-ri also includes demonstrably later grave mounds such as Ssangsach’ong or Mach’ong. Both are stone chamber graves with corridors that occurred around the middle of the sixth century.

Sarah M. Nelson argues that because of some distinctive items such as an impressive gold crown and a golden belt the female occupant of the northern mound held for some time the rule and that this ‘fact’ was omitted from the official sources (Sarah Milledge Nelson, Gyeongju. The Capital of Golden Silla (London and New York: Routledge, 2017), 90–91). This conclusion rests, however, on a number of disputable interpretations, which, for lack of space, cannot be discussed here. The other extreme is represented by Chu Hŏn Lee (Juheon Lee), who argues in a detailed analysis of the excavation report and the artefact spectrum that the occupant of the northern grave was not a female at all (Lee Juheon, “Kyŏngju hwangnamdaech’ong pukpun chuin’gong sŏnggyŏk chaego (Reconsidering the character of the occupant of Kyŏngju Hwangnamdaech’ong northern tomb),” Sillamunhwa 45 (February 2015): 1–34).

The assumption that the kolp’umjedo (bone rank system) or a predecessor is already reflected in the graves of the maripkan-period is implicitly and explicitly presupposed in a number of studies that deal with the ranking of the graves (compare note 1 above).

Lee Hee-Joon, “4 ~ 5segi silla kobun p’ijangjaŭi poksikp’um ch’akchang chŏnghyŏng (On Costume Accessories Worn By the Deceased at Silla Tombs of the 4th and 5th Centuries),” Han’gukkogohakpo 47 (August 2002): 63–92.