한성기 백제의 확장과정에 대한 대안적 접근

An Alternative Approach to the Expansion of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period

Article information

Abstract

한반도 고대국가 중의 하나인 한성기 백제의 확장과정은 그동안 문헌사학 및 고고학의 주요 연구 주제 중 하나였다. 하지만 많은 연구가 문헌에 기록된 한성기 백제의 경계가 실재하였다는 전제를 토대로 진행되었으며, 이와 함께 한성기 백제의 경계 및 영역은 중심부에서 동심원적으로 확장되었다고 인식하였다. 이로 인해 한성기 백제 주변지역의 고고학 자료의 다양성과 그 의미에 대해서는 충분히 설명되지 못하였으며, 한성기 백제의 확장은 주변지역에서 일률적으로 이루어진 것으로 해석되었다. 하지만 고대국가의 경계는 현대 국가와는 달리 유동적이었으며 명확하게 구분할 수 없을 것이라는 점이 지적되어야 한다. 또한 고대국가의 확장과정은 중심지로부터의 물리적인 거리뿐만이 아니라 정치, 지리, 경제적 등 다양한 요인에 의해 지역에 따라 서로 다른 방식으로 영향력을 확장했을 가능성이 고려되어야 한다. 본 연구는 이러한 점을 염두에 두고 중부지역 한성기 백제의 토기의 출토양상을 한강 이남지역과 한강 이북지역으로 나누어 비교함으로써 한성기 백제의 확장과정에 대한 새로운 이해를 시도한다. 그 결과 한성기 백제는 한강 이남지역에서는 영향력을 크게 확대한 반면, 한강 이북지역에서는 일부 거점을 확보하는 수준에 머무른 것으로 생각된다. 이처럼 백제의 확장은 두 지역에서 상이한 확장과정을 보였던 것으로 생각되며, 이는 두 지역이 처한 서로 다른 지정학적인 위치로 설명될 수 있다.

Trans Abstract

The expansion of Paekche, one of the ancient states established on the Korean Peninsula, during the Hansŏng Period was one of the major historical archaeological research topics. Many studies were conducted under the premise that the boundaries of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period as recorded in historical documents had existed in real life, and scholars believed that the boundaries and territory of Paekche at the time spatially expanded in concentric rings around the core. These studies were unable to provide an adequate explanation of the diversity or the significance of archaeological resources acquired from the regions surrounding Paekche during the Hansŏng Period, as the expansion of Paekche was understood to have occurred uniformly throughout the surrounding areas. However, it is important to note that, unlike the boundaries of modern states, boundaries of ancient states were flexible and not clearly defined. In addition, it is necessary to take into consideration the possibility that the expansion of ancient states occurred in different ways throughout different regions due to political, geographical, and economic factors as well as their physical distance from the center. This study takes into account these possibilities and compares the regions to the south and north of the Han River by examining the excavated Paekche pottery from the Hansŏng Period in the central region of the Korean Peninsula to better understand Paekche’s expansion process. It also demonstrates that Paekche expanded its influence in the region south of the Han River during the Hansŏng Period while it only maintained several bases in the region north of the Han River, thereby explaining that the expansion of Paekche differed in the two regions due to the differences in the regions’ geopolitical dynamics.

Introduction

The purpose of this study is to propose an alternative approach to the existing understanding of the expansion of Paekche, one of the ancient kingdoms established on the Korean Peninsula. Historical records and archaeological evidence show that social complexity increased rapidly on the Korean Peninsula around 1 CE, giving rise to polities of various sizes. This study focuses on Paekche, which is presumed to have developed into a state in the mid- to late-third century. Prior to an invasion from the ancient kingdom of Goguryeo, which prompted Paekche to move its capital to Ungjin in 475, Paekche conquered polities in the areas surrounding Hansŏng (modern-day Seoul) and grew politically, economically, and socially. This period is referred to as the Hansŏng Period, and the kingdom’s ruling system over the regions outside of the capital area and the process of its territorial expansion have been important topics in the fields of history and archaeology.

Spatial boundaries, regional ruling systems, and expansion processes have been frequent topics of research in world archaeology. Until the late 1980s and early 1990s, research on ancient states focused on the advent of states, mainly addressing how to generally define the states, how to differentiate them archaeologically, and how to determine their domains. However, in the later years, the neo-evolutionary model of sociopolitical typology of political organizations (bands, tribes, chiefdoms, and states) that was used to explain social development and the advent of states were criticized many times for being too unilinear.1, In addition, discussions began to emerge on the possibilities of diverse processes of the advent of ancient states depending on the historical contexts of different regions, and research began to shift toward the examination of an individual state’s expansion strategies and its interrelationships with surroundings polities.2, Moreover, scholars have suggested in recent years that existing models of modern states create prejudices in the study of ancient states, which needs to be redressed.3

It would be a mistake to apply Western discussions on ancient states directly to Paekche during the Hansŏng Period. However, the criticism that researchers need to shy away from preconceptions that arose from models of modern states is valid, since many discussions on Paekche during the Hansŏng Period have taken place under the presumption that the boundaries between polities could be clearly defined or that the center exercised equal levels of political and economic influence across its domain. The process of Paekche’s expansion has been uniformly interpreted, and the reasons for the diversity of material culture in the outlying regions of Paekche have not been sufficiently explained. In this paper, I aim to examine these critiques in depth and propose an alternative interpretation for explaining Paekche’s expansion in the central region of the Korean Peninsula during the Hansŏng Period.

The Issue of Paekche Boundaries and Territory in the Hansŏng Period

Archaeological research on Paekche commenced in earnest in the 1980s with the excavation of the Sŏkch’on-dong burial site and the Mongch’on earthen wall site. Similar to general archaeological studies, initial research focused on chronological dating. In particular, the main task was to pinpoint the exact time the Proto-Three Kingdom Period end-ed, and the Hansŏng Period began—meaning the exact time in which Paekche was established as an ancient state.4 Later on, as archaeological remains on Paekche began to increase dramatically, research on the expansion of Paekche became another major research topic in the field.

Determining the territorial boundaries of Paekche has been one of the most prominent topics in Paekche studies. While the boundaries of Paekche during particular points in time and the related changes in its territory have been discussed in many studies, it is important to note that many of these studies have been framed around the presumption that Paekche had boundaries and therefore scholars can estimate the extent of its domain by searching for its boundaries. This presumption was particularly prominent in discussions based on the record from the thirteenth year in the reign of King Onjo, written in the Samguk sagi (History of the Three Kingdoms):

(A) 遣使馬韓 告遷都 遂畵定疆埸 北至浿河 南限熊川 西窮大海 東極走壤

An envoy was sent to Mahan and informed them of the relocation of the seat of government. Finally, the boundaries have been set—P’aeha (浿河) to the north, Ungch’ŏn (熊川) to the south, Taehae (大海) to the west and Chuyang (走壤) to the East.

(A) states the boundaries of Paekche at a particular point in time. There are several records in the Samguk sagi that allow scholars to estimate the boundaries and the territory of Paekche, but (A) is the only one that clearly defines Paekche’s boundaries. As a result, the time that (A) refers to and the location of the places mentioned in (A) are still under rigorous debate even in the field of history based on literal sources. In terms of the time period, this record is found under the thirteenth year in the reign of King Onjo (6 BCE), but it is believed that the record was created retroactively based on the circumstances of the time of King Koi (234–286 CE) or King Kŭnch’ogo.5 In terms of the location of the places mentioned as boundaries, scholars generally agree that the western boundary of Taehae and the eastern boundary of Chuyang refer to the West Sea and Ch’unch’ŏn respectively, but the northern and southern boundaries are still under debate. However, an important point to note is that the discussions on the locations mentioned in the above record are ongoing because many scholars continue to accept that Paekche’s boundaries as written in the Samguk sagi actually existed. Researchers continue to frame their arguments under the presumption that, just like the modern states, Paekche had real boundaries during the Hansŏng Period as recorded in the historical documents.

The same presumption has also been applied to archaeological research. Many of the existing studies on the expansion of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period use archaeological resources to define the boundaries of Paekche during particular points in time and determine the scope of its territory. There are two premises on which these arguments are based:

➀ Boundaries of a polity can be determined, and the space within the boundaries is the polity’s territory.

➁ Similar material cultures are shared within a polity.

Based on these premises, archaeological studies in the past have estimated the territory of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period depending on the existence of Paekche pottery. Areas with potteries similar to the ones found in the central region of Paekche were considered as a part of Paekche territory, while those where no such potteries were uncovered were not regarded as Paekche territory. These arguments assumed that material culture in the periphery of Paekche’s domain changed at the time Paekche expanded its domain. As a result, scholars presumed that the material culture of the periphery changed in line with that of the core, and this assumption has inhibited them from considering the regional characteristics of the material culture.

The discussion on Paekche during the Hansŏng Period must be preceded by a questioning of the idea that Paekche had clear-cut boundaries during the Hansŏng Period. Many scholars, both foreign6, and Korean,7, have pointed out that boundaries of ancient states were organic and would not have been marked clearly or in a single line. An archaeological study of Inka and Mayan states also argue that it is nearly impossible to determine the boundaries of ancient states and that the boundaries were always shifting.8, Furthermore, there are cases of modern states with contentious borders that are difficult to determine based on a single standard.9 In consideration of these factors, firmly demarcating the territory of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period may be an impossible task.

In addition, it is important to avoid the tendency to rely excessively on historical records in archaeological studies on the expansion of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period. The chronology of pottery from the periphery of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period was not necessarily created based on archaeological analysis. Instead, scholars used historical records to estimate Paekche’s territory at particular points in time and analyzed archaeological findings under the assumption that regions within Paekche’s territory would have had the same material culture as the center. And the resulting archaeological chronology was used as evidence for historical records, thus creating a circular logic. For instance, Paekche pottery from the Hansŏng Period excavated in the Honam region is often classified as relics from the mid-fourth century, during the time of King Kŭnch’ogo, based on historical records studies that King Kŭnch’ogo of Paekche territorialized this area. This archaeological finding is then used to support King Kŭnch’ogo’s southern expansion.

Historical records have been used predominantly in the study of ancient states, as they allow historians to understand the historical circumstances that cannot be derived from archaeological findings. However, it is important for archaeological studies on Paekche during the Hansŏng Period to sufficiently consider the fact that archaeological research that relies on historical records can potentially hinder the possibility of diverse interpretations of archaeological resources and result in the lack of independent archaeological theories and methodologies.10, It is necessary to conduct research while bearing in mind the various possibilities that have not been recorded in documents. For instance, one study argues that there is a strong likelihood that historical records about the territories of the Assyrian and Roman empires may not be factual but mere expressions of idealized images of the empires, and that that the records may be exaggerated versions of the facts.11 Similarly, there is a distinct possibility that the spatial boundaries of Paekche’s territory during the Hansŏng Period were not clearly defined, contrary to the presumptions in the discussion of the early state. It is also possible that the core exercised influence on certain parts of the periphery near its border, such as Ungch’ŏn and P’aeha, and exaggerated its influence in historical documents, making it seem as though Paekche had influence across the regions surrounding those areas.

Considering all of these factors, scholars conducting studies on the expansion of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period must be aware of the following: first, boundaries of Paekche during this period cannot be clearly defined, and therefore it may be impossible to determine the territory, which refers to the space within the confines of its boundaries; and second, it is necessary to examine the spatial formation and changes of the political entity rather than focusing on determining the scope of Paekche’s territory under the assumption that the extent of its political space had been fixed at the time.

An Alternative Model for the Expansion of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period

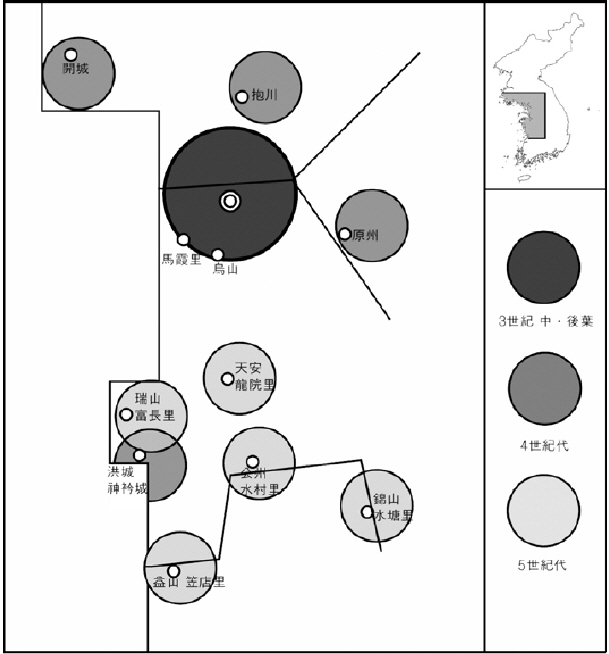

When establishing the boundaries for an ancient state, scholars automatically assume that the areas within the boundaries were the spatial territory of the state. Therefore, the idea that Paekche had clear-cut boundaries during the Hansŏng Period leads scholars to presume that the expansion of Paekche during this period occurred spatially. This presumption has led the academy to overlook the diversity of material culture that can exist in different regions within Paekche’s boundaries as well as the differences in the state’s expansion processes across regions. Figure 1,12, which shows the changes in Paekche’s territory during the Hansŏng Period according to existing studies, is a case in point. In Figure 1, all regions within the boundaries of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period have been marked as Paekche’s territory.

Concepts that have been used to explain Paekche’s territory and regional ruling systems during the Hansŏng Period in archaeology and history include: direct/indirect rule; territory, sphere of hegemony, and sphere of influence; alliances, affiliations, and coalitions; and the strategic-base rule and territorial rule. Among them, all but the strategic-base rule presume that Paekche underwent spatial expansion. In particular, the concept of direct/indirect rule has been applied in the broadest fashion. Generally speaking, direct rule refers to a system of government in which regions are controlled by the central government, while indirect rule refers to a system in which the central government rules through a tribute system or by granting prestige goods to local ruling elites.13, It was also believed that initially the regions closer to the core were under direct rule while regions in the periphery were under indirect rule, but gradually Paekche expanded its direct rule throughout its periphery as its administrative authority became properly aligned over time.14 Therefore the idea of spatial expansion is inherent in the direct/indirect rule model.

The territory, sphere of hegemony, and sphere of influence model can be described as a more detailed version of the direct/indirect rule model.15, The alliance, affiliation, and coalition model was applied to Paekche in order to explain the diverse relationships between the core and the periphery.16 Although these models have been used for different purposes, ultimately they also presume that Paekche expanded its spatial territory, similar to the indirect/direct rule model. All these models focus on the types of relationships between the core and the periphery, but all assume that Paekche underwent territorial expansion in concentric rings around the core over time.

On the other hand, the idea of spatial expansion is not necessarily embedded in the strategic-base rule. The strategic-base rule is a system in which the core establishes trading bases or bridgeheads in order to gain access to the peripheral zones.17, Conceptually, under the strategic-base rule, the areas surrounding Paekche’s strategic bases received relatively less influence from Paekche. In his research on the Shin’gŭmsŏng site in Hongsŏng, Seong argues that the site was one of Paekche’s strategic bases and that Paekche did not expand its territory in concentric rings around the core but by securing major bases.18 This study effectively illustrates the concept of the strategic-base rule.

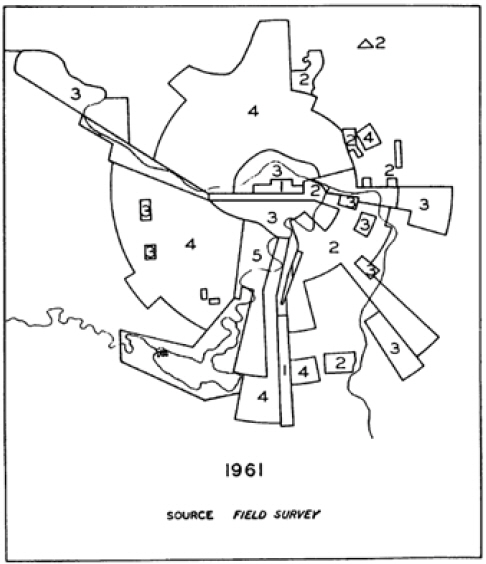

In archaeological studies on Paekche during the Hansŏng Period, the strategic-base rule model came to be used in investigating the Shin’gŭmsŏng site in Hongsŏng and the Pŏpch’ŏlli site in Wŏnju. At these two sites, more pieces of pottery and prestige goods from Paekche were discovered than in the surrounding areas, and the concept of strategic-base rule was particularly useful for explaining the reasons for this discovery. Since then, areas concentrated with artifacts from Paekche during the Hansŏng Period compared to their surrounding areas are considered to have been strategic bases for Paekche. This concept is illustrated in Figure 2,19, which is a diagram of Paekche’s regional ruling system during the Hansŏng Period. Figure 2 shows the regions where the material culture of Hansŏng Paekche were concentrated, and these regions are considered to have been Paekche’s strategic bases.

The strategic-base rule model is similar to Monica L. Smith’s node-corridor model for early states.20 Based on biological research, Smith argued that for the sake of efficiency a state does not expand its spatial territory but exercises influence on the areas where it might gain economic and political benefits and focuses on controlling and managing the transportation routes between these areas. Since a state does not begin its expansion with spatial or territorial expansion in mind, there may be areas where the center’s political influence is unreachable. If we accept this argument, it becomes highly plausible that the ancient state of Paekche also expanded by ruling certain bases rather than having even control over its territory.

The problem, however, is that while the strategic-base rule model can explain the archaeological resources from the peripheral regions of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period, as shown in Figure 2, the results of the model ultimately do not differ much from other models that assume Paekche’s spatial expansion in interpreting the archaeological resources. If we assume that Hansŏng Paekche ruled its peripheries based on the strategic-base rule rather than the territorial rule, as shown in Figure 2, it is theoretically possible for Paekche’s culture to have spread relatively slowly in the regions between the strategic bases or for the peripheries to have kept their local culture alive. Unfortunately, the ideas derived from the strategic-base rule have not been considered in interpretations of the numerous archaeological resources until now. As a result, the regions surrounding the Shin’gŭmsŏng site in Hongsŏng, which was considered to have been a strategic base for Paekche as previously mentioned, have been chronologically dated to have existed around the same time as the Shin’gŭmsŏng site, despite the lack of Paekche pottery discovered in these areas.21, One study also asserts that the material culture of the areas surrounding Paekche during the Proto-Three Kingdom Period and the material culture of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period changed in similar ways at similar points in time.22 As a result, regional diversity was not taken into consideration even in the studies that employed the strategic-base model. Such research trends seem to be the result of the bias in studying related records—that the central region of the Korean Peninsula must have been part of Paekche’s territory during the Hansŏng Period.

The recent critique for the need to consider the regionality of material culture also addresses this bias. Scholars have begun to point out the possibility that the time of Paekche’s expansion might differ from the time material culture in the regions began to change. One scholar argues that it is possible for the traditional pottery of the Proto-Three Kingdom Period—Jungdo-type plain pottery—to have lasted for a relatively longer period of time, depending on the region.23, Others also argue that the distribution networks for pottery in the Proto-Three Kingdom Period were confined within each region,24, and a study on short-necked jars from the Ch’ungch’ŏng region shows that there were discrepancies in the jars discovered in different areas of the region.25 In consideration of the results of these studies, it would be incorrect to assume that the central region of the Korean Peninsula was uniformly influenced by Paekche, and it is necessary to examine the material remains without the assumption that Paekche underwent spatial expansion.

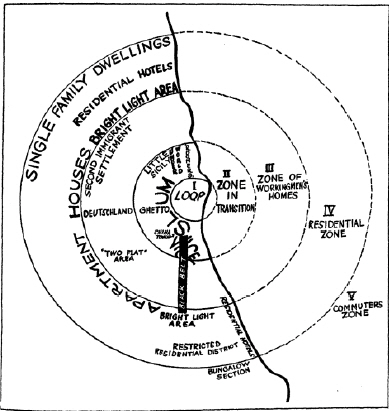

Additionally, we also need to consider the possibility that the process of Paekche’s territorial expansion during the Hansŏng Period differed by area. As can be seen in Figure 1, the discourse on Paekche’s territorial expansion has assumed that Paekche’s boundaries grew in concentric rings around the core and expanded the physical distance to the periphery. This is similar to the concentric zone model (Figure 326,), which is used to explain urban social structures in geography.27

Since the emergence of the concentric zone theory, however, geographers have criticized the unilinear expansion model that simply relies on the distance from the core and have proposed alternative theories. One of the major alternatives is Hoyt’s sector theory.28, As shown in Figure 4,29 the main characteristic of Hoyt’s model is that, unlike the concentric zone model, urban expansion allows for different forms of growth in regions depending on the benefits, such as transportation routes, or geographical importance. In addition, it allows for the possibility of varying roles and importance of areas that are equidistant from the center. This implies that studies of the expansion of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period should also consider the possibility that the ancient state might have expanded its sphere of influence in different ways throughout the surrounding regions, depending not only on the regions’ physical distance from the core but also on geographical, political, and economic factors.

In consideration of the discussion above, it is important to reexamine the existing preconception that Paekche underwent a process of spatial expansion during the Hansŏng Period and to take into account the possibility that Paekche’s expansion process may have differed depending on the region. In addition, it is important to bear in mind that not only the distance from the core but also transportation routes as well as geographical or economic importance of certain regions and geopolitical factors might have been important variables in Paekche’s expansion. The next section discusses this point.

Expansion of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period: Comparison of the Regions North and South of the Han River

This section examines the distribution of settlement sites in the Kyŏng-gi and Kangwŏn provinces where pottery from the Proto-Three Kingdom Period to Paekche’s Hansŏng Period were found. These provinces are generally presumed to have been have been ruled by Paekche during the Hansŏng Period. Based on the results, I would like to examine the differences and the cause of these differences in Paekche’s expansion during the Hansŏng Period.

Figure 5 shows the settlement sites where Jungdo style pottery, a type of pottery from the Proto-Three Kingdom Period (around 1 CE to the third century), or Paekche-style pottery from the Hansŏng Period were excavated. As the illustration shows, the settlement sites where Paekche-style pottery were excavated are distributed throughout a broader region and more concentrated to the south of the Han River than to the north. In addition, more settlement sites to the south of the river saw their local traditions and cultures from the Proto-Three Kingdom Period replaced with Paekche culture during the Hansŏng Period compared to the north, and more new settlements were created in the south of the river during the Hansŏng Period than north of the river. These aspects can be explained by one of the two reasons described below.

Distribution of Settlement Sites in the Central Area of the Korean Peninsula Where Jungdo-style Pottery or Paekche-style Pottery Were Excavated

➀ Parts of the areas to the north of the Han River were wiped out when Paekche emerged during the Hansŏng Period.

➁ The material culture of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period did not spread as much to the north of the Han River as it did to the south of the Han River.

Theory ➀ accepts the existing chronology. Based on historical records, the areas surrounding the Han River were presumed to have become part of Paekche’s territory after it developed into a state. And, as mentioned above, some of the existing chronologies assume that the material culture of the areas included in a state’s territory changes to conform to the culture of the core. In order for this idea to be proven, the phenomenon depicted in Figure 5 can only be explained by a rapid decrease in the number of settlement sites to the north of the Han River after Paekche developed into a state. However, it is difficult to accept the explanation that only this region became less inhabited for no particular reason. In addition, radiocarbon dating has revealed that Jungdo-style pottery from the Proto-Three Kingdom Period found in this area had continued to be made even in the Hansŏng Period.30

Therefore, theory ➁ is more convincing for explaining this phenomenon. Theory ➁ implies that during the Hansŏng Period Paekche did not expand in concentric rings but that there were differences in its expansion process to the north and south of the Han River. It seems that Paekche exercised a great amount of influence in most areas to the south of the river, while it only maintained relationships with several major strategic bases to the north of the river. As a result, most of the areas to the north of the Han River remained outside of Paekche’s influence during the Hansŏng Period, which makes it highly likely for the existing local culture to have lasted for a longer period of time.

It is now important to discuss the reasons for the differences in Paekche’s expansion strategies in the regions south and north of the Han River even though there was not much of a difference in the physical distance between these regions and Hansŏng, the then capital of Paekche. To this end, it is necessary to consider the geopolitical location of the two regions. A polity’s space can be divided into areas that are relatively safe in terms of political and military risks, such as hinterlands, and areas bordered with other polities of equal status and therefore face higher military risks. It is also possible to predict that the expansion strategies of a polity would differ greatly depending on the military threats. This means that Paekche would have had to invest the minimum amount possible to maintain its influence in the regions with high military risks, while investing more and exercising more influence over the areas with relatively lower risks. With this in mind, the archaeological differences of the two regions can be explained as follows:

If we accept the aforementioned strategic-base model, the ancient state of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period would have expanded by occupying major areas with political advantage first and by managing the transportation routes from the capital to these areas. Also, it would have secured transportation routes in the surrounding areas that were of lesser importance and exercised influence over them in order to eliminate the risks of the transportation routes to major bases being severed. If this process continued throughout the region, Paekche would have ultimately been able to exercise influence across the whole region, which then could be called Paekche’s territory. It seems that this process continued throughout the region south of the Han River.

On the other hand, it is possible that Paekche stopped at securing bases in certain areas in the region to the north of the Han River due to geopolitical differences from the region south of the river. Around the time Paekche became an ancient state, there were the four commanderies of Han to the north, which was replaced by the ancient state of Goguryeo after the commanderies withdrew from the region. Paekche had been constantly at conflict with the commanderies and later Goguryeo. This means that unlike in the region to the south of the Han River, the region to the north of the river was constantly at risk of being invaded by Goguryeo and Nangnang despite Paekche’s investment in the region by securing bases and transportation routes. For this reason, it seems that Paekche only secured several bases in areas of strategic importance and did not proceed with additional expansion to the north of the Han River, which was relatively more dangerous than the region south of the river, resulting in the image depicted in Figure 5.

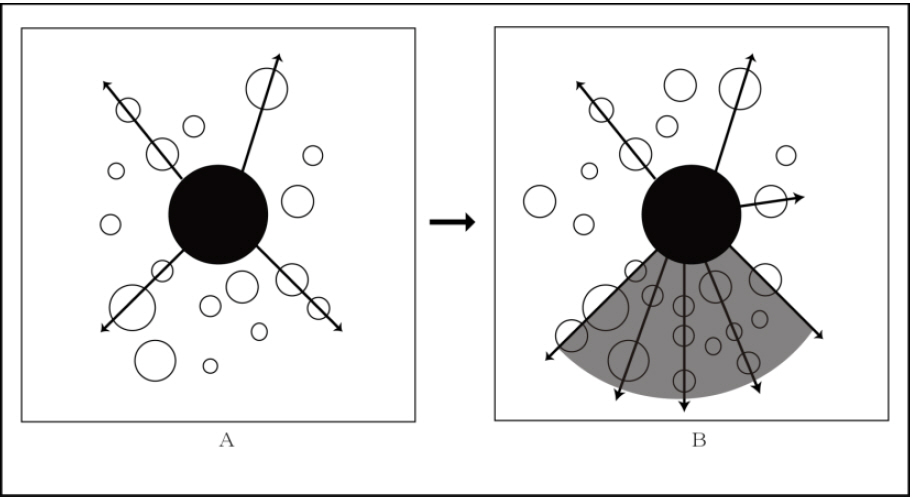

The diagram of the expansion of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period based on the above theory would be similar to Figure 6. The black circle in the center is the core of Paekche, while the smaller circles in the surroundings refer to smaller polities in the surrounding regions. The lines represent the direction to which Paekche expanded to secure bases, and the shaded area is the area over which Paekche ultimately came to exercise its influence. With Paekche’s expansion, the surrounding areas would have gradually changed from A to B.

Initially, Paekche expanded by securing bases in each region for economic and political advantages. In the region with fewer risks, Paekche was able to exercise its influence stably and make profits and, as a result, came to manage a larger number of bases and transportation routes compared to the region with higher risks. Therefore, Paekche came to exercise its influence over the region to the south of the Han River, while in high risk areas, such as the region to the north of the Han River, Paekche delayed additional expansion. This could explain the differences in the expansion process of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period. Moreover, this theory allows scholars to consider the possibility that Paekche employed different strategies for different regions, resulting in different levels of expansion in the regions. However, this explanation is a preliminary one that only takes into consideration the geopolitical factors of the regions to the south and north of the Han River, and it will be necessary to perform additional analysis by factoring in other major variables, such as transportation routes as well as geographical and economic factors. This would allow for a more indepth discussion of the regional differences in the expansion of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period.

Conclusion

The use of historical records was a major part of the methodology in archaeology for studying the expansion of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period. Historical documents have been useful in explaining and interpreting archaeological resources, and they also help overcome the limitations of archaeological information and reconstruct historical circumstances in a more vivid manner. However, sometimes they create bias and obstruct diverse interpretations that can be made from archaeological resources.

Research on the expansion of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period is an example of problems that could arise from the use of historical records. In previous studies, Paekche’s boundaries as recorded in historical documents were accepted as facts and were regarded as clear-cut boundaries of modern states. As a result, these studies presumed that Paekche expanded spatially in concentric rings from the core to the periphery. This interpretation of Paekche’s expansion ignored the differences in the material culture of Paekche’s surrounding areas during the Hansŏng Period and created a linear expansion process. However, scholars should guard against readily accepting the boundaries of an ancient state like Paekche that have been recorded in historical documents. In addition, when historical documents and archaeological data provide conflicting information, it is important to conduct analysis with a variety of alternate possibilities in mind. Through this methodology, it will be possible to construct a more dynamic expansion process of Paekche during the Hansŏng Period.

Notes

Richard E. Blanton, Gary M. Feinman, Stephen A. Kowalewski, and Peter N. Peregrine, “A dual-processual theory for the evolution of Mesoamerican civilization,” Current Anthropology 37, no. 1 (February 1996): 1–14.

Norman Yoffee, Myths of the Archaic State: Evolution of the Earliest Cities, States, and Civilizations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Roderick B. Campbell, “Toward a Networks and Boundaries Approach to Early Complex Polities: The Late Shang Case”, Current Anthropology 50, no. 6 (December 2009): 821–848.

Katharina J. Schreiber, Wari Imperialism in Middle Horizon Peru, Anthropological Papers of the University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology 87 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology, Ann Arbor, 1992).

Adam T. Smith, The Political Landscape: Constellations of Authority in Early Complex Polities (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003).

Park Soon-barl, “A study on the early Paekche pottery of Han river valley with the emphasis on the pottery chronology and the historical status of Mongch’on earthen wall,” MA Thesis of Seoul National University, 1989.

Park Soon-barl, Hansŏng Paekche-ŭi t’ansaeng (The birth of Hansŏng Paekche) (Seoul: Sŏgyŏng munhwasa. 2001).

Moon An-sik, “A Study on the Transition of north territory and east territory in Hanseong Period of Baekje,” Paekche Yon’gu 44 (August 2006): 1–33.

Lim Ki-hwan., 2013, Paekche-ŭi tongbukbangmyŏn chinch’ul – munhŏnjŏk ch’ŭkmyŏn (The advancement of Paekche into the Northeast – from literary perspective), Kŭnch’ogowang-ttae Paekche yŏngt’o-nŭn ŏdikkajiyŏnna (How far did Paekche’s territory expand during the reign of King Kŭnch’ogo) (“Chaengjŏm Paekchesa” chipchungt’oron haksulhoeŭi charyojip (collection of papers from the “Controversial history of Paekche” academic conference), Seoul Baekje Museum, 2013).

Justin Jennings, “Core, peripheries, and regional realities in Middle Horizon Peru,” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 25, no. 3 (September 2006): 346–370.

Bradley J. Parker, “At the edge of empire: conceptualizing Assyria’s Anatolian Frontier ca. 700 BC,” Journal of anthropological archaeology 21, no. 3 (September 2002): 371–395.

Kim Ki-seob, “Paekche nambangyŏngyok hwakchang-gwa Chŏnnam chiyŏk (Expansion of southern Paekche and the South Chŏlla region),” Chonnam chiyŏk Mahan cheguk-ŭI sahoe sŏnggyŏk-gwa Paekche (Social characteristics of the Mahan empire and Paekche in the South Chŏlla region) (2013 nyŏn Paekche hakhoe kukche haksulhoeŭI charyojip (collection of papers from the 2013 International Academic Forum of the Association of Baekje Studies), 2013).

Kim Jongil, “A critical review on theory and methodology of archaeology in nationalism,” Han’guk Sanggosahakbo (Journal of Korean Ancient History) 96 (May 2017): 251–276.

R. Alan Covey, “A processual study of Inka state formation,” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 22 (December 2003): 333–357.

Charles W. Golden, “The politics of warfare in the Usumacinta Basin: La Pasadita and the realm of Bird Jaguar,” in Ancient Mesoamerican Warfare, ed. Brown, M. K. and T. W. Stanton (CA: Altamira, 2003).

Richard Scofield, “Borders and territoriality in the Gulf and the Arabian peninsula during the twentieth century, “ in Territorial Foundations of the Gulf states, ed. R. Schofield (London: University College, 1994).

Ander Andren, Between Artifacts and Texts (New york: Springer, 1998).

Choi Jong-taik, Lee Young-seon, Lee Jae-yong and Kim Jang-suk, (Radiocarbon Dating and the Historical Archaeology of Korea: An Alternative Interpretation of Hongryeonbong Fortress II in the Three Kingdoms Period, Central Korea),” Journal of Field Archaeology 42 (February 2017): 1–12.

Tina L. Thurston, “Historians, Prehistorians, and the Tyranny of the Historical Record: Danish State Formation through Documents and Archaeological Data,” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 4 (September 1997): 239–263.

Monica L. Smith, “Networks, territories and the cartography of ancient states,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95, no. 4 (November 2005): 832–849.

Park, Hansŏng Paekche-ŭi t’ansaeng.

Lee Do-hak, “Paekche-ŭi kyoyŏngmang-gwa kŭ ch’egye-ŭi pyŏnch’ŏn (Paekche’s trade network and the changes in its system),” Hankuk hakpo (Journal of Korean Studies) 63 (June 1991).

Yoo Won-jae, “Paekche-ŭi yŏngyok pyŏnhwa-wa chibang t’ongch’i (The change in Paekche’s territory and regional governance),” Han’guk Sanggosahakbo (Journal of Korean Ancient History) 28 (September 1998): 147–163.

Kim Yong-sim, “Yŏngsangang yuyŏk kodaesahoe-wa Paekche (Ancient society in the Yŏngsan River basin and Paekche),” Chibangsa-wa chibangmunhwa (Journal of Local History and Culture) 3, no. 1 (July 2000).

Kim Yong-sim, “Sabi-sigi Paekche-ŭi yŏngyŏk (Paekche’s territory during the Ungjin and Sabi periods),” in Kodae Tong’asia-wa Paekche (Ancient Eastern Asia and Paekche) (Daejeon: Paekche Research Institute of Chungnam National University, 2002).

Kim Seong-nam, “Preliminary Thoughts on the Southern Expansion of the Paekche State and its Control over Regional Polities,” Paekche Yonku 44 (August 2006): 35–84.

Kim Yong-sim, A Study on the local government system of Paekche from the 5th century to the 7th century (PhD thesis, Seoul National University, 1997).

Seong Jeong-yong, A study on early Paekche pottery of mid-western Korea, (MA Thesis of Seoul National University, 1994).

Park Soon-barl, “Some Patterns of Early Paekche’s Local Cemetery Continuation in View of Localization of Periphery by Political Center,” Han’guk Kodaesa Yŏn’gu (Journal of Korean History) 48 (December 2007): 155–186.

Smith, “Networks, territories and the cartography of ancient states,” 832–849.

Monica L. Smith, “Territories, Corridors, and Networks: A Biological Model for the Premodern State,” Complexity 12, no. 4 (March 2007): 28–35.

Seong Jeong-yong, “On the Tombs and Pottery of the 4–5 Centuries of Kum River Valley,” Paekche Yonku 28 (December 1998): 65–134.

Han, Ji-sun, “The Transformation Process of Hansung Baekje Era settlement and Pottery group,” Chungang Gogoyŏn’gu (Journal of Central Institute of Cultural Heritage) 12 (June 2013): 1–59.

Kim, Junkyu, A relative chronology of the Jungdo style plain pottery: focusing on potteries from Northern Gyeonggi and Western Gangwon regions (MA Thesis of Seoul National University, 2013).

Sim Jae-yeon, “Hanseongbaekjae in the Youngdong-Youngseo Region,” Gogohak 8, no. 2 (December 2009): 51–68.

Kim Jangsuk and Kwon Oh-young, “Paekche Hansŏng yangsik t’ogi-ŭi yut’ongmang punsŏk (An analysis of the distribution network for Hansŏng Paekche-style pottery),” Paekche saengsan’gisul-ŭi paldal-gwa yut’ong ch’eje hwakdae-ŭi chŏngch’I sahoe-jŏk hamŭi (Sociopolitical implications of the development of the production system and the expansion of the distribution network in Paekche) (Seoul: Hagyŏn munhwasa (Hakyounmunhwasa), 2008).

Kim Jangsuk, “A Chronology of the Proto-Three Kingdom Period in Northern Chungcheong: Cheongju, Cheongwon and Cheonan Areas,” Han’guk Kogohakbo (Journal of Korean Archaeology Society) 77 (December 2010): 47–96.

Ernest W. Burgess, The Growth of the City: An Introduction to a Research Project (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1925).

Of course, since the geographical model mentioned here focuses on urban expansion, it would not be right to directly apply this model to the expansion of an ancient state. However, I believe that the model’s explanation of the aspect of spatial expansion from the core to the periphery can provide useful implications for the studies on Paekche’s territorial expansion during the Hansŏng Period.

Homer Hoyt, The Structure and Growth of Residential Neighborhoods in American Cities (Washington, D. C.: Federal Housing Administration, 1939).

P. J. Smith, “Calgary: A Study in Urban Pattern,” Economic Geography 38, no. 4 (October 1962): 315–329.

Kim Jangsuk and Kim Junkyu, “Radiocarbon Dates and Pottery Chronology of the Proto-Three Kingdoms and Three Kingdoms Periods-Central, Hoseo, and Jeonbuk Areas of Korea,” Han’guk Kogohakbo (Journal of Korean Archaeology Society) 100 (September 2016): 46–85.

Kim Junkyu, “A relative chronology of the Jungdo style plain pottery: focusing on potteries from Northern Gyeonggi and Western Gangwon regions”.