조선 말기 왕실 사용 유럽 도자: 생산, 분석, 평가

European Porcelain for the Royal Court in the Late Chosŏn Dynasty: Production, Analysis and Evaluation*

Article information

Abstract

본 연구는 19세기 말 20세기 초, 조선 왕실에서 서양식 연회와 일상용기로 사용 했던 유럽 도자기 식기 및 집기에 주목하고 그 도자기들의 종류, 원료, 제조사, 생 산연도 등을 분석하였다. 개항 이후 서구와 같은 근대국가 수립을 지향하며 여러 형태의 서구식 의례를 도입하려 했던 대한제국정부는 궁중연회에서도 서양식 연 회를 여는 경우가 늘어갔다. 이러한 연회에 사용할 식기류는 프랑스, 영국, 독일의 도자기 제조회사에서 수입했다. 또 황실의 일상생활에서 사용되었을 도자기 집기 들 역시 이들 국가의 도자기제조사에서 수입되었다. 기존의 박물관 도록 및 이전 연구가 한국과 프랑스의 도자 교류나 대한제국기 공예품에 새겨진 왕실 문장 분석 에 국한된 반면 본 연구에서는 기존 연구의 오류를 바로잡고 고종의 개혁정책이 황실 의례의 변화와 서양 자기의 도입에서 어떻게 드러나는지 살펴보았다. 또한 외교의 중심지였던 정동지역에 위치한 덕수궁과 손탁호텔에서 서양식 연회에 사 용되었던 유럽 자기가 당시 최고의 산업 기술과 각 생산지의 원료로 제작되어 한 국 이외의 여러 서양국가에도 보편적으로 수출된 것임을 알 수 있었다.

Trans Abstract

In accordance with the accession of the Emperor and establishment of the Korean Empire, Kojong’s government mandated modification of the traditional way of receiving envoys by altering rituals to fit the West, with Western style banquets using European tableware. These tableware and toiletry were imported from France, Britain and Germany. This study examines European porcelain in terms of stylistic features, production technology and periodization. While previous museum catalogues provide general information on the European porcelain, existing scholarship is limited to French-Korean relations in porcelain production and the armorial crest on craftworks of the Korean Empire period. Through careful analysis of European porcelain, this study revises errors in the catalogues. The examination of each object, made of durable and innovative material compounds produced with the best industrial production technology of the time, ultimately demonstrates the Chosŏn court consumed Western porcelain in pursuit of a modern state.

Introduction

Korea’s reluctant opening of its ports in 1876 to Japan subsequently set a pattern of unequal treaty relationships between Korea and Western powers. As a response to the growing presence of Western powers and Japan, Kojong implemented various political, social, and economic measures to modernize the state. This included a rearrangement of state rituals in accordance with Kojong’s reformative strategy. The arrangement of state rituals was required for consolidating the order of the state and the royal family. Thus, Kojong required rearranging state rituals in accordance with his accession as the Emperor and the subsequent establishment of the Korean Empire.1

With an increasing number of diplomats, Western style legations in Western style established in the Chŏngdong2, area and the Sontag hotel3, (where Western style banquets were held), became the hub of diplomacy. Thus, Kojong’s government required modification of the traditional way of receiving envoys in accordance with Western manners which followed with Western style banquets.4, This Western style banquet was managed by the Foreign Ministry Office, including the management of appropriate tableware.5, However, by the end of the 19th century, the Chosŏn royal kiln faced the inevitable fate of privatization6, and limited financial support failed to produce good quality wares. Besides, mass-produced cheap Japanese porcelain dominated the domestic market.7 Moreover, the Korean government was going through an reformative era. Kojong’s efforts to modernize the nation are demonstrated in the importation and usage of European porcelain at the Western style banquet. In such banquets, both tableware and food were Western style. The tableware, tea and coffee ware and toiletries were imported in sets from France, Britain and Germany.

Hence, Kojong’s declaring himself as the Kwangmu Emperor in 1897 and initiating the modernization strategy is reflected in the adaptation of Western style banquets with imported European tableware. While the achievement of Kojong’s reform and the legitimacy of the state have been questioned by current scholarship, I argue that imported European porceporcelain and its usage demonstrates Kojong’s attempt to legitimize Korea as a modern state like advanced Western powers. As he also invited foreign figures to formulate foreign policy, 8 his effort to find a national identity by incorporating Western style banquets is demonstrated through the usage of imported porcelain.

Regardless of its significance, within the field of modern Korean art history, the study of imported porcelain has been overlooked. Perhaps this was because imported porcelain was considered as lacking in aesthetic value, mass produced industrial wares as they were. Researchers were probably also hindered by scarce resources. Fairly recently, however, the topic has started to draw attention among art history scholars on related subjects.9, But such previous studies were limited to French-Korean relations or focused on the armorial crest of the Korean Empire applied on crafts produced during the Korean Empire period. Furthermore, the general museum catalogues10, published by the National Palace Museum of Korea (hereafter, NPMK), only serves to show the lack of scholarship with its inaccurate information that leaves a great deal to be revised. In addition, the artifact search device of the NPMK website offers the same information as the first catalogue. Thus, the primary goal of this research is to shed light on an overlooked field of Korean modern history by establishing the foundation of the European porcelain collection and providing revisions of misread porcelain marks as well as the information on manufacturers and purpose of production.

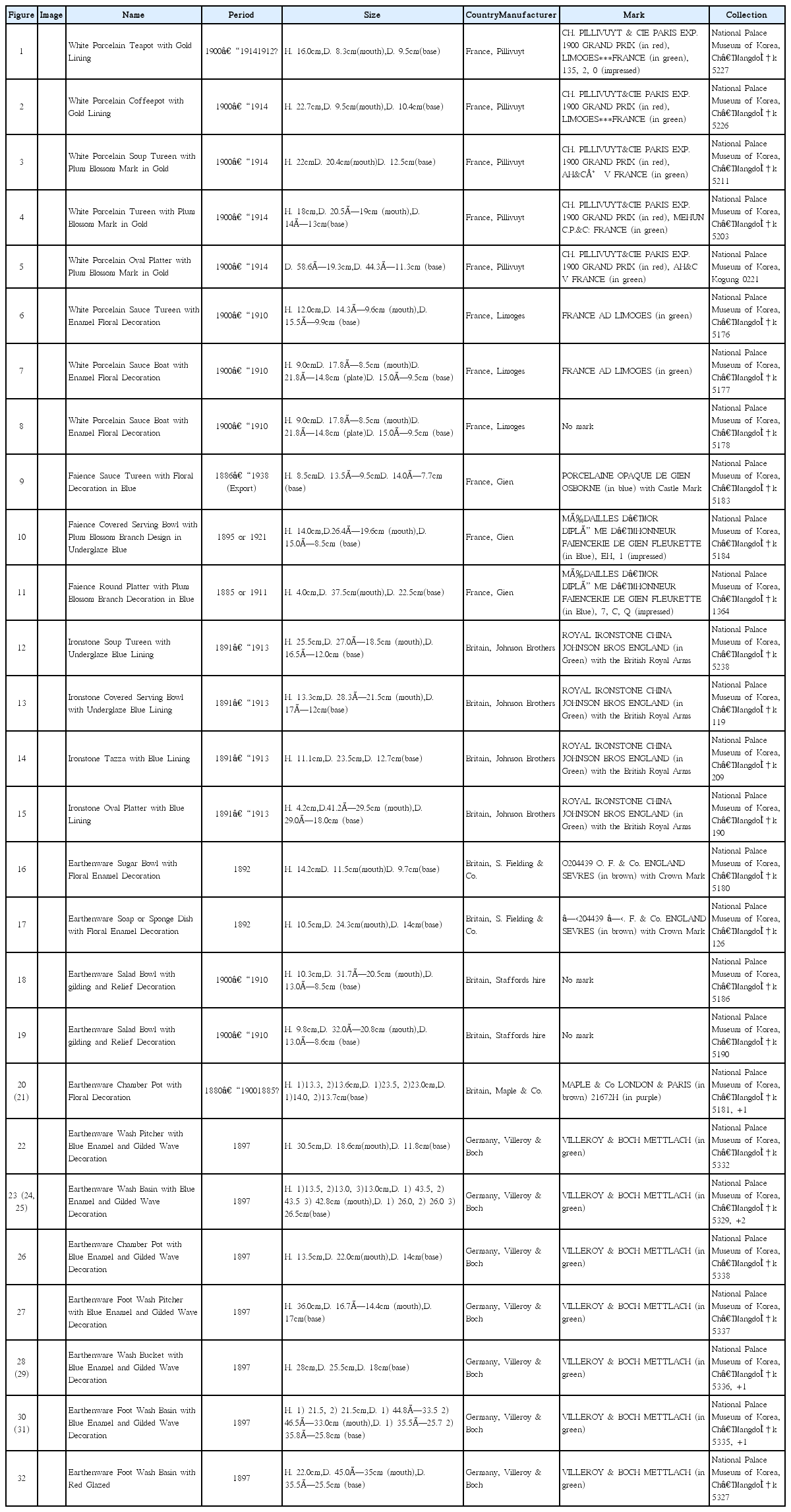

This article will examine the thirty-two pieces of European porcelain at the NPMK and each object is analyzed in terms of stylistic features, production technology and periodization with marks as shown in Table 1. This data has been collected through an examination of primary sources, a close observation of the objects with several handling sections at the NPMK. The handling section was an essential part of this research, as a principal part consists of revision of the misread marks, manufactures and usage. Ultimately, identified features of the imported porcelain will broaden the perspective in understanding Kojong’s modernization strategy within the context of holding Western style banquets.

European Porcelain at the Western Style Royal Banquets

The usage of European porcelain in Western style banquets is well demonstrated in the two rare paintings, the Banquet Celebrating the Korea-Japan Trade Treaty, an 1883 (Figure 63) work by An Chungsik and the Modern Style Banquet at the Cho Pyŏngsik’s House, 1888 (Figure 64). The painting of 1883 depicts a banquet scene, held at the government office in Chŏngdong area. The person seated on the left side of the table is Min Yŏngmok (1826–1884), the Minister Plenipotentiary of Korea, and to the right is Takezoe Shinichirō (1841–1917) and to the left is Paul George von Möllendorff (1848–1901), a diplomatic advisor stationed in Korea.11

Banquet Celebrating the Korea-Japan Trade Treaty, 1883 An Chungsik, Soongsil University Korean Christian Museum

In previous studies of the Banquet painting of 1883, Chu demonstrated good insights about the seating orders of the participants and the specific list of food that may have been served. In the brief description of the tablewares that he described was a white porcelain teapot and Punch’ŏng ware hexagonal bowl with a cover.12 However, the Punch’ŏng ware is less likely to be used on this treaty table, considering the production of the time, though it may have been brassware or other metal ware used together with imported porcelain from Japan, France and Britain. The other banquet painting of 1888 depicting the banquet at Cho Pyŏngsik’s House seems a more casual setting with one person in the lower right corner of the painting using chopsticks. The huge flower vase on the center of the table is a Western style table setting whereas the banquet painting of 1883 is more reserved. The white porcelain plates and glass goblets in various shapes and silverware are presumably imported from Europe and Japan.

This tableware for the banquet may have been managed and lent by the Oebu (外部, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs). As Lee has discussed in ‘Taehanjaeguk’ Gŭndaeshik’ Yŏnhŭi’ article,13, in May 1899 and April 1904, the Hakbu (學部, the Ministry of Education) requested the loan of banquet items to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The specific list of items include plates, soup tureens, sauce plates, dessert plates, noodle bowls, vegetable plates, butter plates, forks, soup spoons, knives, coffee wares, coffee spoons, beer glasses, champaign glasses, wine glasses, spittoons, table napkins, etc.14 From these records, such tableware, various glassware and teaware were used at the banquet offered by the Ministry of Education for foreign teachers.

The European porcelain imported during this period also may have been used at various royal banquets offered at the court managed by Antoinette Sontag (1854~1925). Miss Sontag was Karl Waeber’s (1841–1910, the Russia’s first consul general to Korea) brother-in-law’s elder sister, and she came to Korea in 1885 with Waeber’s family. She was originally from Alsace-Lorraine, France, but because of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 by which the region merged into Germany, she became a German citizen. When she came to Korea, she was thirty-two and she could speak four languages: English, German, French and Russian. Since the United States-Korea Treaty of 1882, with the increase in number of foreign diplomats, the Korean government sought after a person proficient in many languages.15

Accordingly, Waeber recommended Sontag and she started to work at the Korean Household Department. She successfully managed and arranged all the banquets for both domestic and foreign officials held at the court with her French cuisine.16, As is also mentioned in Sadao’s book,17, when King Kojong returned to Kŏnch’ŏng Palace at Kyŏngbok Palace in 1885, he commissioned Sontag to refurbish the interior including furnishing goods and tableware. It is worth mentioning that while Sontag was working for the Korean Household Department, she served King Kojong with Western cuisine and coffee.18, According to the Mutel Diary, Sontag also was in charge of arrangement of the banquet for the King’s birthday.19 As such Sontag established herself in the diplomatic society as an important figure and her hotel was at the center of Chŏngdong Club’s social gatherings. Undoubtedly, Miss Sontag played a significant role in distributing and using European porcelain at royal banquets.

Manufactories and Marks of European Porcelain

There are about thirty-two pieces of European Porcelain (Table 1) in the collection of the National Palace Museum of Korea. These wares were manufactured from three different countries, France, Britain and Germany, and imported to be used at the Chosŏn royal court throughout the open port period.

Porcelain Manufactured in France (Table 3)

Among the European porcelain in the collection at the National Palace Museum of Korea are various kinds of tableware and teaware that are manufactured in France such as Pillivuyt, Limoges and Gien.

Pillivuyt

There are five pieces, one teapot (Figure 1), one coffeepot (Figure 2), two tureens (Figure 3, 4) in different shapes and one oval platter (Figure 5) manufactured from the Pillivuyt porcelain manufactory in France. These are all white porcelain with gold lining decorations and both tureens and the plate are marked with the Yihwa (Flower of Yi dynasty), a plum blossom which is the national emblem of the Korean Empire (1897~1910). This armorial crest indicates that these tableware were specially commissioned for the royal court. This kind of table service could be ordered with any number of pieces and varied according the client’s needs. For royal households these were usually extensive and may well have had extra or specially commissioned pieces added to the order.

According to the Pillivuyt catalogue, the factory developed its own porcelain compound on-site at the factory. Porcelain compound is hard paste obtained from blend of kaolin, clay, feldspar and quartz. 20, The abundant source of kaolin deposit which is the core part of consistent production is evident from the chart demonstrating the ceramic industry in the late 1980s.21 Thus, these tableware were presumably produced with the kaolin and clay compound found near the factory and fired at high enough temperature to make it durable quality ware. The delicate vine scroll shaped handle and acorn shaped finial would have been made from the molds.

These tableware are all marked with the ‘CH. PILLIVUYT & CIE PARIS EXP. 1900 GRAND PRIX’ (in the previous catalogues, the ampersand is between CIE & PARIS) in red, which indicates the company won the prize at the International Exhibition of 1900 and that it has proudly proclaimed that fact on the pieces of their porcelain. These pieces must post-date 1900 and was probably made c. 1900–1914. Getting more precise dating for the production of these wares is possible through the examination of the plum blossom, the armorial crest on the tureens and plate. There is a form and style of sauce-tureen (Figure 33) from Noritake manufacture almost identical to that of the Pillivuyt tureen (Figure 4). The blossom marks on both tureens are made in very similar manner, which indicates that they were either produced or imported around the same time. According to the preceding research on the emblem marked on the crafts produced during Korean Empire period, the pattern of the blossom changes over the period. The change has been studied by comparing blossom patterns on the Pillivuyt (Figure 34) and the Noritake (Figure 35) porcelain. The blossom mark on the earlier Noritake porcelain is similar with Pillivuyt piece which has blossoms with even length of stamen in radial form22, Noritake tureen with the same Pillivuyt mark has the production mark (Figure 36) of ‘RC/Balance symbol/ Nippon Toki Kaisha’ in green which indicates the production date is 1912.23 Thus, under the premise that the emblem mark is not a later addition, the Pillivuyt table wares are most likely produced or imported around the same time.

The additional marks on the Pillivuyt porcelain need farther interpretation. Besides Pillivuyt mark, on the teapot there is ‘LIMOGES ***FRANCE’ in green and impressed numbers, ‘135’, ‘2’, ‘0’ (Figure 37) and ‘MEHUN C.P. & C: FRANCE’ (Figure 38) on a tureen (Figure 4) and ‘AH&C V FRANCE’ (Figure 39) on a soup tureen and an oval platter (Figure 3, 5). Since Mehun is where Pillivuyt were operating, C.P. & Cie is for Pillivuyt & Cie at Mehun sur Yèvre or porcelain could be made in Limoges and sold or decorated at Mehun or Vierzon since they are both about 180–200km from Limoges, but they were all manufacturers; it could be that they were using porcelain made in Limoges and applied their mark. And the numbers would indicate the form or size of the vessel.

Limoges

There are three pieces of tableware with the mark of Limoges, one sauce tureen (Figure 6) and two double-lipped sauce boats (Figure 7, 8) with printed floral decoration. In the museum catalogue24, and website25 these objects are labeled as soup tureen and bowl. It is proper to revise as sauce tureen and sauce boat. Also from the catalogue the mark on the tureen is ‘FRANDE SIMOGES’ and on the sauce boat is ‘OSBORNE’ with a castle mark. However, after examining the pieces, it is clear this was misread and recorded. Both a tureen and a sauce boat were marked as ‘FRANCE AD LIMOGES’ (Figure 40). Thus, these tableware are produced in Limoges, the center of porcelain production in France. From the decoration of the piece these are circa 1900–10 and typical of their products with colored enamels. However, the ‘AD’ mark, which seems to be the maker’s initials, cannot be identified, due to the lack of information.

As Limoges porcelain designates hard-paste porcelain produced by factories near the city of Limoges, France, beginning in the late 18th century and does not refer to a particular manufacturer, the pieces without a factory mark or an unidentified maker or design styles is very difficult to place. In fact, by 1850, there were more than 30 manufactories operating at Limoges and their history is very complicated, not only because of the large number, but because they also emerged and disappeared depending on political and economic crises.26, However, the stylistic features can be compared with the other Limoges factories such as Havilland27, and Royal Limoges.28 As Haviland is considered the most famous Limoges brand and Royal Limoges the oldest existing porcelain factory in Limoges, other manufactories at Limoges would have been influenced by both factories. The museum piece with a swirling wave motif in relief molded body with overglaze printed floral decorations and touch of gilding on the rims is comparable to the typical pieces produced from the both factories of the period.

Gien

In the National Palace Museum, there are three pieces of tableware that can be identified as Gien porcelain; one sauce tureen (Figure 9), one serving bowl with cover (Figure 10) and one round platter (Figure 11). The catalogue does not provide enough information about these wares but the round platter is marked with ‘FAINENCERIE DE CIEN’ which suggests that the ‘Gien’ could be misread as ‘Cien’. Examination of the object made it possible to identify that all three works were from Gien, distinguished with the mark on the foot; the sauce tureen with ‘PORCELAINE OPAQUE DE GIEN OSBORNE’ (Figure 41) in blue with the castle mark, a serving bowl with ‘MÉDAILLES D’OR DIPLÔME D’HONNEUR, FAIENCERIE DE GIEN FLEURETTE’ (Figure 42) in Blue and ‘EH’, ‘1’ impressed, a platter with same mark as serving bowl but with ‘7’,’ C’, ‘Q’ impressed.

Since 1821, the Faïencerie de Gien marked each piece coming out of its factory. In 1852, Gien began marking its products with a letter and started with A. Following years would each have the next alphabet letter and this until 1877, 26 years for 26 letters. And every 26 years the font changed. From 1930 the marking procedure was changed: one letter of the alphabet would indicate two years, a second letter would indicate the month when the piece was manufactured (A for January, B for February, etc.), and sometimes a third letter would identify the craftsman.29

Thus, according to the Gien trade mark catalogue, the sauce tureen with the castle mark could be matched with the mark which was used from 1886 to 1938. However, the detailed outline is more closer to the export mark. Thus, the sauce tureen would be for export in the final quarter of the 19th century. As it is seen from the mark, ‘PORCELAINE OPAQUE’ also indicats it is faience, a type of earthenware of high quality, which is made to look like Chinese porcelain with its opaque white glaze. The ‘OSBORNE’ mark within the banner is a pattern name which corresponds with the decoration motif on the piece. The blue transfer printed floral decoration is distinctively English. Osborne was also the name of Queen Victoria’s Osborne House, situated at East Cowes on the Isle of Wight, a former country retreat of Queen Victoria and her consort, Prince Albert.

The mark (Figure 42) on a serving bowl and a round platter matches the trade mark used from 1875 indicating it is faience and commemorating the gold medal from the exhibition. The ‘FLEURETTE’ is a pattern name as well. The impressed ‘EH’ mark (Figure 43) on the tureen, according to the date code would be E=May, H=1885(unlikely as it is probably too early) or 1911. And ‘CQ’ (Figure 43) could be either C=March Q= 1895 or 1921. These are less likely after 1930. Certainly Europe was very unstable at the time and there was little export trade as there was in the late 19th century and early 20th century, i.e. from 1880 until the outbreak of WW1 in 1914. The numbers 1 and 7 could indicate the mark of different sizes or forms.

Porcelain Manufactured in Britain (Table 3)

The collection of British porcelain at the National Palace Museum of Korea is mostly dinner service and only one toiletry is known. The majority of dinner ware is from Johnson Brothers. There is a sugar bowl from S. Fielding & Co. Two salad bowls, whose the maker is unknown, as well as the chamber pot with the Maple & Co. mark will be discussed in more detail in this section.

Johnson Brothers

There are four pieces of tableware from Johnson Brothers, one tureen (Figure 12), one serving bowl with cover (Figure 13), one tazza (Figure 14) and one oval platter (Figure 15). These tableware, which have been also used as a complete set, are decorated with the simple blue linings decoration are typical Staffordshire ironstone. All of them have mark of ‘ROYAL IRONSTONE CHINA JOHNSON BROS ENGLAND’ (Figure 44) in Green with the British Royal Arms. According to the mark book the factory started in 1883 and the printed or impressed mark ‘JOHNSON BROS’ was used from 1883 to 1913. Also the ‘ENGLAND’ added after 1891.30

The simple blue underglaze hand painted decoration and molded classicizing details are in line with typically well-designed, usable wares produced around the turn of the century. The ‘ironstone’ is a robust pottery body which is a type of hard white earthenware fired at high temperature to partly vitrify it. It was introduced in England early in the 19th century by the Staffordshire potters who looked for a substitute for porcelain that could be mass-produced for the cheaper market. The result of their experiments was dense, hard, durable stoneware that came to be known by several names, for example semi-porcelain, opaque porcelain, English porcelain, stone china, new stone-all of which were used to describe essentially the same product. It was patented by Charles James Mason of Lane Delph in Staffordshire in 1813. Mason used a mixture of Cornwall clay, ironstone slag, flint and blue oxide of cobalt to produce a hard, opaque, bluish white pottery that had a smooth, glossy finish after glazing and firing.31

S. Fielding & Co

The sugar bowl (Figure 16) with the cover missing and a soap or sponge bowl (Figure 17) which had been with a liner and cover but missing are from S. Fielding & Co. The information provided by the museum catalogues and the website were all different. Only after handling the piece was the mark identified as ‘O204439 O. F. & Co. ENGLAND SEVRES’ (Figure 45) in brown with Crown Mark. Regarding the ‘F. & Co.’ mark, it is listed as Thomas Fell and Co. of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, although Godden’s Encyclopedia of marks suggests they closed in 1890. Also the ‘England’ mark is usually after 1891. There is another problem with this attribution as Fell’s did not use a crown mark.32

Therefore, the pieces are more likely to be S. F. & Co. for Fielding’s Pottery of Stoke on Trent, in the Staffordshire Potteries. The firm was founded in 1879 and these initials and crown mark was in use from 1891 to 1913. ‘Sèvres’ is presumably the pattern name which loosely resembles the French style rococo ornament with flowers and scrolls which is also apparent on these wares with curvilinear lines in relief and transfer and enameled decorative combination of flowers. The number ‘204439’ would be the design-registration number which is prefixed by ‘Rd’ or ‘N’ from 1884 that according to the Godden’s Illustrated Guide book, it is 1892.33

Unknown Maker

There are two salad bowls which does not have a maker’s mark. There are wreath decorations in relief on both sides of the interior and gilded along the rims. They may well have been the part of large dinner service. The pieces with no mark is difficult to place, but it could have been made in Britain or possibly France or Germany in the late 19th or early 20th century, although I would expect it to be marked, were it English, at least with the ‘England’ mark which was applied by law from 1891. With regards to the dating, Anton commented that these seem to be earthenware, in other words pottery, probably date from circa 1900–10 and probably Staffordshire.34 Thus, these earthenware salad bowls are presumably produced at one factory in Staffordshire in the turn of the century and imported as a part of large dinner set.

Maple & Co

In the museum catalogue and website, there is a bowl (Figure 20) with the mark of ‘MAPSE & CLONDON & PADON 21672’. However, this is a typical shape of a chamber pot which may have been part of a wash set with a large water-jug and basin, toothbrush-box, sponge-dish and etc. The decoration is transfer and then with overglaze enamels. After handling the piece the mark is identified as ‘MAPLE & Co LONDON & PARIS’ (Figure 46) in brown with the pattern number of 21672H in purple, like the one on the Fielding pieces.

The Maple & Co. was not a maker of porcelain but was one of the largest and most successful British furniture retailers and cabinet makers in the Victorian and Edwardian periods.35, Thus, the chamber pot, presumably earthenware with the classical-style printed decoration, would have been made for Maple &Co and the retailer’s mark applied to it. According to Peter Hyland, the editor of Northern Ceramic Society, Maple & Co. had a very famous shop in London where these high quality wares were sold. The date of the chamber pot would have been 1880–1900 and it is difficult to say which manufacturers produced the porcelain for Maple & Co. There have been a number of manufacturers, but from the decoration, it could be from Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, as they are known to have made ceramics for Maple & Co.36 Thus, the chamber pot would probably be from Staffordshire, earthenware and 21672 is the pattern number, so a retailer could reorder the same pattern from the manufacturer and from the Godden’s guide, 21672 is from 1885. Also the ‘H’ would indicate the location of the firm within the Staffordshire Potteries and H stands for Hanley, where the Wedgwood had their Etruria Works from 1769 to 1950.

German Porcelain Manufactories (Table 3)

In the National Palace Museum collection there are toilet sets manufactured from Villeroy & Boch (Table 3) in Germany, which is still in production worldwide. From the existing works, it is assumed that many sets of toiletries were imported as there are several pieces of the same wash basin and wash buckets.

Villeroy & Boch

As is also seen from its production history, Villeroy & Boch was noted for its Mettlach tiles and wash sets. Among the European porcelain collection at the National Palace Museum, the number of toiletries from Germany is comparatively large. In fact, all eleven pieces of toiletries are made from Villeroy & Boch. In the process of handling some of these wares at the museum storage, I encountered several pieces which had never been published. Moreover, considering that there are several identical pieces of the same wash basin, there must have been many sets of these wares ordered together.

The wash pitcher (Figure 22), three identical wash basins (Figure 23), two identical wash buckets, etc. indicate that at least three wash sets in this blue enamel decoration had been ordered. Furthermore, a chamber pot (Figure 26), a foot wash pitcher (Figure 27) and a foot wash basin (Figure 32) in red glaze have not been published before. In fact, the museum catalogue and website have classified these wares as English porcelain. However, the pitcher (Figure 22) and a wash basin (Figure 23), which are the only two objects on view at the moment, have been revised as being from Germany. Besides, some of these wares have been incorrectly labeled and this will be discussed in more detail with the sales catalogue of the Mettlach factory.

These wares belonged to a washing or toilet set named ‘Weser’, the name of a German river, produced during the years about 1890 till the beginning of the 1930s. The material is earthenware and the pattern is hand painted. It was exported to many European countries as well as to the United States, South America, Scandinavia and Australia.37

As it is seen from the cover of the 1897 sales catalogue of Mettlach factory, 38 all of the Villeroy & Boch pieces in the collection have a matching Mettlach mark (Figure 47) in green. First, the catalogue is in French, Italian and Spanish, which indicates possible export destinations. The catalogue provides images of each piece with the name, size and price per different sizes and decorations on the piece. For example, a wash pitcher of a bigger size (H. 29.5cm, same as the one in museum) with blue or purple enamel gradation and gold decorations is 750 centimes, which would be about 6 euros. Thus, from this sales catalogue, it is possible to know the price value of the wash pitcher of the period and it is possible to picture the entire toilet set which was been imported from Villeroy & Boch. Although there are no brush and soap dish or sponge box remaining in the collection, these items would have been ordered as a set together. It is worth noting that, from the ‘goods’ section of the catalogue, what has been recorded in the museum catalogue as a kettle should be a wash pitcher or jug (Figure 22), an ice cube box should be revised as wash bucket (Figure 28) and a punch bowl as a foot wash basin (Figure 30).

As not everyone had piped water in the bathroom in the late 19th century, many Europeans had a special piece of furniture called a washstand in the bedroom designed to hold a large water jug and washing bowl. When not in use the jug would stand in the bowl as part of the decorative room furnishings. There were sometimes smaller matching pieces for holding soap, hairpins, cosmetics etc. Such an interior setting is well demonstrated at the present display of Sŏkchojŏn Hall in Tŏksu Palace, which has been recently restored to its original setting.

Evaluation and Analysis of the Imported European Porcelain

Based on the analysis of the European porcelain at the National Palace Museum, the wares imported by the Chosŏn royal court had several commonalities. First these were generally mass produced industrial wares, intended for the well situated family in the middle class range market. Second, most of the manufactories were actively involved in export activity and some of the products were intended specifically for the export market, though in terms of manufacturing method, each of the factories was incorporating their highest technology and material to produce light and durable ware to be used in everyday life. Lastly, compared to that of Japanese or Chinese porcelain imported around the same period, the imported porcelain was not of the best quality, targeted for the middle class, mass produced and intended for export market.

The Pillivuyt factory, based right in the heart of France in the Berry region, produced wares with its own porcelain compound on-site at the factory with the highest standards of quality. There are several examples of table services ordered with crest are found. At the Historic New England Museum in Boston Massachusetts, there are about 334 pieces of Pillivuyt tablewares composed of 110 dinner plates, 85 salad plates, 28 saucers, 28 soup plates, 18 demitasses. The Pillivuyt tureen with ‘P’ (Figure 48) and plate (Figure 49) and these pieces originally belong to the Phillips House in Salem, Massachusetts. It is all marked with ‘CH. PILLIVUYT & CIE PARIS EXP. 1867 MEDAILLE D’OR’, thus presumably produced ca. 1900.39, The overall shape of the tureen with the acorn shaped finial, gold banded edges and monogram ‘P’ marked is very similar to the tureen (Figure 4) ordered by the Chosŏn court. Another example of such ware is in the collection of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. The Cream Pitcher (Figure 50) and cream cup (Figure 51) with crest of William T. Walters. The diaries of George A. Lucas, a Paris-based art agent, record that he and William T. Walters coordinated the ordering of a set of crested Sèvres porcelain in late 1864. More items were ordered in the following years, from Sèvres or directly from Pillivuyt, often by the dozen. The same monogram (the intertwined initials “W.T.W”) appears on the bindings of William’s albums of drawings, and his napkins, glassware, and stationary.40 Such monogram dining services were essential items in wealthy 19th-century households and these examples, including the Chosŏn court’s Pillivuyt tureen, demonstrate that this kind of table set had been widely produced and exported worldwide.

The Johnson Brothers factory produced light weight and durable ironstone ware and was widely exported to various countries, especially the United States market. At its peak in the 1960s, production approached 1,000,000 pieces per week. The comparable example to the tureen (Figure 12) at the museum is often found in the present day antique market, which demonstrates the huge export scale of the firm. The identical shape of tureen (Figure 52) with the mark of ‘ROYAL IRONSTONE CHINA JOHNSON BROS ENGLAND’ but without the underglaze blue decoration indicates it has been mass produced from the same mold. The other tureen (Figure 53) with the J.W. Pankhurst & Co. (Figure 54) mark which is the former firm of Johnson Brothers and the piece with typical mark would have been produced between 1852 and 1863 which indicates typical form have been produced prior to the Johnson Brother’s production. Such objects are not dedicated works so it is less likely collected by museums or collectors, thus the comparable examples can be considered as part of a private collection.

The S. Fielding & Co. is the same case as Johnson Brothers in that numerous comparable examples are found in auctions. The sugar pot (Figure 55) with the same mark and pattern registration number, ‘204439’ (Figure 57) as the museum’s sugar pot (Figure 16) is in identical form and the enamel floral decoration. This comparable example even has the lid similar to the original shape of the lid of the museum piece and is traceable as well as the mark. Also the teapot (Figure 56) of the same mark, registration number and Sèvres style of decoration that gives an idea that it has been used together as a tea set with the sugar pot. According to the trade journal article on S. Fielding in 1893, the firm was equipped with the latest machinery: three powerful engines which to grind the own material to save cost of production and five ovens, including several for glazing and seven kilns, the largest in the Potteries. There were four hundred employs including ninety who were skilled decorators. The products they manufactured were earthenware in toilet, dinner and tea wares, jugs, teapots and ornamental goods. There were also show rooms in various countries and goods are exported to the United States and all the British Colonies. Factories were also equipped with special transport facilities such as their own railway siding and adjacent to canals.41 From this account it is very convincing that such wares of tea sets and toiletries had been imported Korea at the time.

Lastly, as it is discussed in the previous section, the Villeroy & Boch collection at the museum corresponded exactly with the 1897 sales catalogue samples of the Mettlach factory.42 For example, Wash Pitcher (Figure 58), Wash Basin (Figure 59), Foot Wash Pitcher (Figure 60), Foot Wash Basin (Figure 61), Wash Bucket (Figure 62) and etc. all match with the wash set at the museum. This catalogue is in French, Italian and Spanish, which indicates the possible countries where the same kinds of pieces had been exported and the fact that the firm was specialized in sanitary and washing sets from mid-19th century demonstrates the wash set at the museum is typical export ware of the time.

Conclusion

Every piece from France, Britain and Germany was carefully analyzed in terms of type, material, manufacturer, production technology, and periodization by several handling sessions. The examination of works at the NPMK made it possible to identify the manufacturing countries and producers as well as the dating of the pieces. From the analysis it was concluded that tableware from France were mostly white porcelain and faience, from England ironstone and earthenware and from Germany earthenware toiletries. According to the marks, the imported porcelains were all manufactured between 1890 and 1910, which corresponds with the Korean Empire period.

According to careful examination, the European porcelain collection at the NPMK are made of durable and innovative material compounds produced with the best industrial production technology of the time. In other words, it was mass produced targeting the world market. It was in the late 19th century that the Chosŏn royal kiln was unable to produce for the royal court and mass-produced cheap Japanese porcelain dominated the domestic market. Thus, Kojong’s alliance with the West through his reformative movement as a diplomatic decision to modernize the nation is reflected in the rearrangement of state rituals as well as the usage of European porcelain Western style banquets. At such banquets, both tableware and food were in Western. The tableware, tea and coffee ware and toiletries were imported in sets from France, Britain and Germany. This demonstrates that, even in small quantities, the Chosŏn court acted as a consumer in pursuit of constructing a modern state.

In this sense, I expect this research to bring a new perspective into interpreting the modern history of Korea by proposing a new methodology which seeks not just to understand history from texts but to start the process from small objects, such as pieces of tableware, to unveil parts of history that may have been missed or overlooked. This microscopic to macroscopic approach of study may extend research further through an unconventional analysis in social, political, economic, and cultural fields of study.

Notes

This research was supported by Global PH.D Fellowship Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2014H1A2A1020962).

As Kojong inaugurated the Korean Empire, he changed the title of his reign to Kwangmu, and replaced the traditional Five Rites of State (Kukchooryeŭi, 國朝五禮儀) and the Supplement to the Five Rites of State (Kukchosogoryeŭi, 國朝續五禮儀) with the newly compiled Canon of the Rites of Taehan (Taehanyejŏn, 大韓禮典) which is composed of ten volumes. The tenth volume in the Pillye(賓禮) mentions envoy reception. The modified rituals in overall reflects Kojong’s efforts to gain legitimacy of the Empire and modernize the Korean nation. For a fuller discussion on changes in the rituals, please refer two following articles. Hyung-min Chung, “The ‘Grand Rite’ of the Taehan Empire,” Seoul Journal of Korean Studies 17 (2004); Minhyeok Yim, “Taehanjegukki Taehanyejŏnŭi P’yŏnch’an’gwa Hwangjeguk Ŭirye,” (Compilation of Dahan-Yejeon in the Daehan Empire Period and its Emperor’s Rituals), Yŏksahwa Shirhak (History and Shirhak) 34 (2007).

After Chosŏn opened its door to Western world in 1880s the area became a political hub. Chŏngdong as a birth place of modernity formed with foreign legations, educational institutions, churches, hospitals and so on which transformed the old, traditional views of this area entirely into a modern village. Ch’ŏnsŏng Kim, “Chŏngdong Kŭndaeshik Sŏyang Sukpakshisŏlgwa Sagyok’ŭllŏbŭi Kŭnwŏnjiŭi Yŏn’gu” (A Study of Chŏngdong Area as a Birth Place of Modern Western Accommodations and Social Clubs), Korean Hospitality and Tourism Academe 18 (2009): 329–344.

For detailed studies on Miss Songtag and her establishment of Western style hotel in Chŏngdong and management of royal banquets, refer to two following articles. Wŏnmo Kim, “Miss Sont’akkua Sontag hotel.” (Miss Sontag and Sontag Hotel). Hyangt’o Seoul (Rural Seoul) 56 (1996): 175–220. Sunu Lee, Sontag’s Hotel (Seoul: Hanŭlchae, 2012), 143–206.

Junghee Lee, “Kaehanggi Kŭndaeshik Kungjŏngyŏnhoeŭi Sŏngnipkwa Kongyŏn munhwasajŏk Ŭiŭi” (Formation of early-modern style court banquets and historical meaning of performance culture) (PhD diss., Seoul National University, 2010)

Hakpunaegŏmun 學部來去文 (1899. 5.18~19, 1904. 4.2).

Pyŏngsŏn Pang, “Kojong yŏnganŭi bunwŏn minnyŏnghwagwajŏng, Kojon’g yeon’ganui bunwŏn minnye onghwagwaje-on’g” (Privatization of Bunwon in the Reign of Kojong). Yŏksawahyŏnshil (History and Reality) 33 (1999): 183–216. and Ŭnsuk Pak, “Kaehang hu bunwŏn unnyŏnggwŏnŭi mingan iyanggwa unnyŏngshilt’ae, Kaehan’g hu bunwŏn unnye-onggwŏnui min’gan iyanggwa unnyeongshilt’ae” (Privatization and Operation of Bunwon after opening of the ports). Hanguksayŏngu (Research of Korean History) 142 (2008): 251–294 .

Seung Hui Eom, Iljaegangjeomgi dojasa yeonggu (Research of Ceramics in the Japanese Colonial Period).(Seoul: Gyeongin Publishing Co., 2014).

Hyǒnjong Wang, “Taehanjegukki Kojongŭi Hwangjegwŏn Kanghwawa Kaehyŏk Non-ri” (Kojong’s Reinforcement for Emperor’s Power and His Argument Reform during Korean Empire Period), Yŏksahakpo (History Journal) 208 (2010): 1–23.

In the past few years, the research about the ceramic cultural exchange between Korea and France, Sŭnghŭi Ŏm, “Kŭndaegi hanbulŭi dojagyorŭ,” (The Ceramic Cultural Exchange Between Korea and France in Korean Modern Period), Hangukkŭnhyundaemisulsahak (Korean Modern Art History) 25 (2013) and dating of crafts produced during the Korean Empire period through the comparison of Ihwa, the armorial crest of Korean Empire applied on the French and Japanese porcelain, Inhŭi Song, “Taehanjaegukki hwangshilgongyep’ume nat’anan yihwamunŭi byŏnhwa,” (The Imperial Craftworks of Korean Empire and the Changes in Appearance of Plum Blossom Mark) Yŏksawa Damron (History and Discourse) 67 (2013).

The first catalogue published by the museum in 1997 has compiled the most objects and includes a brief introduction covering also porcelain from China and Japan (The Royal Museum 1997). The revised editions in both Korean (Gukripgogungbakmulgwan 2010) and English (National Palace Museum of Korea 2011) have fewer objects with additional images of marks, but the contents are not too different from the 1997 edition.

Yŏngha Chu, “Shikt’ak’ wiŭi gŭndae: 1883 choilt’ongsangjoyak’ ginyŏm yŏnhoedorŭl t’onghaesŏ” (Modernism on the Table: A Study on the Painting of Banquet Celebrating the Trade Treaty between Chosŏn and Japan in 1883), Sahŭiwa Yŏksa (Society and History) 66 (2004).

Ibid., 21.

Junghee Lee, “Taehanjaeguk’ gŭndaeshik’ yŏnhŭi.” (The Modern Style Banquet During the Korean Empire Period), in Taehanjaeguk’: Ithŏjin 100nyŏn Jŏnŭi Hwangjaeguk’ (Korean Empire: Forgotten History of 100Years Ago), compiled by Kukripkogungbakmulgwan (National Palace Museum), (Seoul: Minsok’wŏn (Folklore Institute), 2011), 347–382.

Lee, “Taehanjaeguk’ gŭndaeshik’ yŏnhŭi,” 363–65.

Lee, Sontag’s Hotel, 187–206.

Kim, “Miss Sont’akkua Sontag hotel,” 178–179.

小坂貞雄, 外人の觀たる朝鮮外交秘話 朝鮮外交秘話, (京城: 朝鮮外交秘話出 版會, 1934), 199.

Ibid.

Ibid., 179.

Pillivuyt, Innovation & Tradition since 1818, (Mehun-sur-Yevre: Pillivuyt, 2013), Accessed February 18, 2015, http://www.pillivuyt.fr/catalogue-pdf/CATA-2013.pdf.

Henri Letourneau, “L’industrie de la porcelaine en Berry et régions voisines. Essai de géographie historique,” 167 (1995): 537.

Inhŭi Song, “Taehanjaegukki hwangshilgongyep’ume nat’anan yihwamunŭi byŏnhwa,” 327.

David Spain, Noritake Fancyware A to Z: a pictorial record and guide to values (PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2002), 28.

The Royal Museum, Oyatghot hwangsilyoumul (Imperial craftworks and plum blossom) (Seoul: Gaemoonsa, 1997).

”Artifacts,” accessed January 4, 2015. http://www.gogung.go.kr/gallery.

Brytz, March 28, 2015, comment on Limoges, The Info Faience Blog, http://www.infofaience.com/en/limoges-hist.

”Haviland History,” Haviland Collectors International Foundation, accessed March 15, 2015, http://www.havilandcollectors.com/HavilandHistory.

”Our Company,” Royal Limoges, accessed March 21, 2015, http://www.royal-limoges.fr/our_company,us,8,13.cfm.

”Gien Trademarks Since 1821,” Gien, accessed February 23, 2015, http://www.gien.com/cms/upload/UserFiles/File/repertoire.pdf.

Arnold A. Kowalsky and Dorothy E., Encyclopedia of Marks on American, English, and European Earthenware, Ironstone, and Stoneware 1780–1980 (PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 1999), 246.

Geoffrey A. Godden, Godden’s Guide to Ironstone: Stone & Granite Wares, (Suffolk: Antique Collector’s Club Ltd., 1999).

Geoffrey A. Godden, Encyclopedia of British Pottery and Porcelain Marks, (New York: Crown Publisher, Inc., 1964), 245.

Geoffery A. Godden, British Porcelain: An Illustrated Guide, (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1974), 29.

Anton Gabszewicz, e-mail message to author, March 21, 2015.

Hugh B. King, Maples Fines Furnishers: A Household Name for 150 Years (London: Quiller Press., 1992).

Peter, Hyland, e-mail message to author, March 16, 2015.

Ester, Schneider, e-mail message to author, March 19, 31, 2015.

Villeroy & Boch, Tarif Illustré des Produits Céramiques Fabriqués à Mettlach, (Mettlach: Villeroy & Boch, 1897), 127–128.

”CH.PILLIVUYT & CIE,” Historic New England, accessed March 15, 2005, http://www.historicnewengland.org/collections-archives-exhibitions/collections.

”Pillivuyt and Co,” The Walters Art Museum, accessed March 14, 2015. http://art.thewalters.org/browse/creator/pillivuyt-and-co.

”Messrs. S. Fielding and Company Railway Pottery, Stoke-on-Trent,” Advertising and Trade Journal, 1893.

Villeroy & Boch, Tarif Illustré des Produits Céramiques Fabriqués à Mettlach, 1897.

References

Hakpunaegŏmun 學部來去文. (1899. 5.18~19, 1904. 4.2).