오늘날 한국과 중국에서의 신화의 귀환, 신화자원, 그리고 신화의 현재성

국문초록

오늘날 신화는 일종의 문화자원으로 활용되고 있다. 과거에도 신화는 문학과 예술 창작에 있어서 영감의 원천이 되어왔지만, 세계화와 급변하는 미디어 환경으로 인해 21세기에 신화가 자원화 되는 양상은 훨씬 더 복잡하고 다변화되었다. 이 글은 이러한 상황에서 한국과 중국 신화학계에 등장한 “신화의 귀환”, “新신화주의”, “신화주의”와 같은 개념을 소개하고, 자원으로 신화가 활용된 몇 가지 예를 통해 신화의 자원화에서 발견되는 경제적, 학술적, 국가적 욕망과, 아울러 이러한 욕망들을 넘어서는 새로운 창조의 가능성을 살펴본다. 그리고 이를 통해 신화의 현재성을 어떻게 이해해야 할 것인지에 대해 논한다.

주제어: 신화의 귀환, 신화자원, 신화의 현재성, 한국신화, 중국신화

Abstract

Nowadays, myth is being used as a kind of cultural resource. Myth has been the source of inspiration for creating literature and art in the past as well, but with globalization and rapidly-changing media environment, the modes of myth resourcization have become more complex and diversified in the 21st century. This paper introduces the concepts that emerged in the mythological circles of Korea and China under these circumstances such as the "return of myth," "neo-mythologism," and "mythologism", and examines a few examples of myth being utilized as resources to get a glimpse of the economic, academic, and national desires that can be found in the myth resourcization. Additionally, it also seeks possibilities for new creation that is beyond these desires, and discusses how we should understand the "contemporaneity of mythology."

KeyWords: return of myth, myth resources, contemporaneity of mythology, Korean mythology, Chinese mythology

What can myth do in this day and age?

What is myth, and what significance does it hold today? What can myth do in this day and age? To put it differently, how can we find contemporaneity of mythology in the contemporary world? On one level, this question emerges out of the struggle in the late 20th century, the decline of humanitarian concerns and the crisis of humanities disciplines due to the progress of science and technology and the development of industrial society. In the 21st century, the pace of change in the media environment and full-scale globalization is leaving little room to contemplate the future of humanities as academic and educational disciplines. Emergence of the so-called “Fourth Industrial Revolution” is being discussed on a global level. The media are saturated with talk about the unemployment of humanities graduates. Students majoring in language or literature at Korean universities are double majoring in management, economics, or accounting as if this was a natural course, and universities are establishing special computer coding classes for humanities majors.

Under these circumstances, what does it mean to teach young students the unrealistic and surreal tales of remote antiquity? Learning mythology in today’s world—can it be anything more than accumulating knowledge about ancient artifacts and remains left by humanity? By examining the roles myths played as well as the manners in which they have been utilized in Korea and China in the past two to three decades, this paper seeks to find the clues to which the “contemporaneity” of mythology can be understood.

“Return of Myths” in Korea

Contrary to the supposedly gloomy prognosis facing humanities disciplines, people’s interest in mythology has been gradually growing in Korea since the mid-1990s. What emerged around that time was the discourse of the “return of myths.” Simply put, what this discourse was saying is that the deepened reflection on the negative effects of industrial society and rationalism has led some to move away from the antagonistic relationship between humans and nature, and toward embracing the mythological worldview, which perceives humans and nature existing in a harmonious relationship, as well as paying attention to the value of imagination over reason.

Those who led the discourse of “return of myths” in Korea at the time were a group of scholars based on a “mook” (a book/magazine hybrid) series entitled Sangsang, which means “imagination” in English. They rediscovered the power of imagination and myth, paying renewed attention to the theory of symbolism by Carl Jung, Gaston Bachelard, Gilbert Durand, and the like, and emphasized the reconciliation between science and imagination. 1 What is interesting about the “return of myths” discussed by these scholars is that it was intricately linked to the “East Asian discourse,” prevalent in the Korean academia at the time. One thing which demonstrated this aspect most prominently is the scholar of Chinese mythology, Prof. Jeong Jae-seo’s book, The Sadness of Eastern Things published in 1996. The objective of this book stated by the author was to “move away from biased knowledge that has supported the imperialist cultural rule of the West, and carry on the tradition of East Asian civilization, in which grand dynamics are newly emerging, with our unique literary vision.” 2 In his view, myths were still relevant in Eastern civilizations, which is the key for humanity to overcome modern rationalism originating from the Western civilizations. It so happens that around this time Yi Yun-gi’s Greek and Roman Mythology was a big hit in 2000, and the animated TV series, Olympus Guardian, which aired from 2002, was quite a sensation. 3 This led to a series of related goods pouring out, and a strange phenomenon of Korean children reciting the names of twelve Olympian gods, while they had little to no knowledge of Korean mythology. Its popularity was huge—so much so that the so-called “Dionysus meme,” which derived from this TV show became popular until quite recently. Of course, the “return of myths” as well as the “restoration of imagination” was not a discourse limited to Korea. The popularity of the Harry Potter series, which swept the world for over a decade since Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone first came out in 1999, is a case in point. Korea was also struck by the global Harry Potter fever and the fad of myth and fantasy genres. Greek and Roman mythology was still mainstream, but books and research related to Asian mythology such as Korea and China were being published diligently. On the one hand, fantasy novels and movies such as The Chronicles of Narnia and Lord of the Rings were loved by the public, and game companies rushed to create games using mythical characters and narratives. As this kind of phenomenon, which was referred to as the “return of myths” by the mythologists continued for quite a while, films like Troy (2004) and Avatar (2009), which either utilized Greek and Roman mythology directly or used mythical imaginations continued to be loved. In some universities, departments with titles such as Culture Contents Studies were established to ride the coattails of the popularity of myths and legends mined by the culture industry.

In the 21st century, specifically Korean myths have also been gaining popularity within various types of new media. In particular, as webtoons as a medium is flourishing in today’s Korea, it has become a common practice for them to be adapted as sources for TV series or films. A large number of webtoons use Korean myths and legends as subject matter. Let us take a look at a few examples below:

Parigongju (Princess Bari)

Two of the largest webtoon platforms in Korea are Kakao Webtoon, which has recently been affiliated with Daum corporation, and Naver Webtoon. Princess Bari is written by Kim Na-im, and has been serialized in Kakao Webtoon from December 2017. Princess Bari is known as the first shaman in the Korean shamanic tradition, whose job was to console and deliver the souls of the deceased. 4 Tale of Princess Bari is a famous myth that has been adapted many times into novels, plays, and musicals. 5 Princess Bari was born as the seventh daughter of King Ogu and Queen Gildae who had six daughters before her and was abandoned by her father who wanted a son. But when her parents fell ill, she went on a quest to the underworld to bring the “water of life” for them. Undergoing all sorts of hardships in the underworld for a long time, she finally brought back “the water of life” and saved her parents. She then decided that she would deliver the souls that she met on her path to the underworld, and was later reborn as the god of the shamans. It is a narrative of hardship, in which unconditional filial piety and woman’s sacrifice is praised. However, Kim Na-im, the author of the eponymous webtoon, resurrects the princess as a 15-year-old apprentice of a shaman in the contemporary world. Here, Princess Bari is not someone who sacrifices herself pressured by someone else but is portrayed as a person who chooses her own path with a sense of agency. She listens to the stories of the victimized souls who died harboring resentment, and makes the perpetrators take responsibility for their wrongdoings. This webcomics borrows the mythical worldview from the tale of Princess Bari and transforms it into a creative fashion to turn it into a story that criticizes absurd reality and lends an ear to the voice of the voiceless.

Kan ttŏrŏjinŭn tonggŏ (My Blood-Curdling Housemate)

Like other East Asian countries, Korea has a rich reservoir of stories about nine-tailed foxes in mythology and legends. In the contemporary period, the nine-tailed fox has been a popular character appearing in a hit anthology TV series called Chŏnsŏl ŭi kohyang (Home of the Legends) and a 1990s’ film, Kumiho (Nine-tailed Fox), and the like.

Recently, good-looking male versions of the nine-tailed fox were loved by readers as they have been depicted in several titles such as A Thousand- year-old Nine-tailed Fox and My Blood-Curdling Housemate. The latter comic, serialized in Naver Webtoon, was adapted into a TV drama on tvN channel last May and enjoyed considerable popularity. It is a romantic comedy between a handsome 999-year-old nine-tailed fox and a confident, high-spirited female college student, who are thrown into a situation to live as housemates and go through all sorts of unexpected events.

Kŭk-lak-wang-saeng (Rebirth in Paradise)

Kŭk-lak-wang-saeng 極樂往生, written by Gosari Baksa, a nom-deplume meaning Dr. Bracken in English, was serialized on a small independent open platform called Dilihub, instead of large-scale webtoon platforms such as Naver and Kakao. 6 The title of the webtoon refers to a Buddhist notion, roughly understood as “rebirth in paradise.” The comics is based on the Korean notion of an underworld, which is a mixture of Buddhism and folk religions. As it became known as an immensely moving and outstanding work through word of mouth, it came to be the representative webtoon on the platform. It received the Minister of Culture, Sports, and Tourism Award in 2019 and is going to be made into a TV series as well.

Sin gwa hamkke (Along with the Gods)

There are many other examples of Korean mythology and legends being utilized for the 21st-century new media, but the most well-known is Sin gwa hamkke [Along with the Gods]. 7

This title was adapted into a two-part motion picture with respective subtitles, The Two Worlds and The Last 49 Days. Both did great at the Korean box office, since part 1 and part 2 all made it into the top 10 box office hits of all time. Part 1, The Two Worlds is ranked in the top 3, attracting 14 million viewers in total. The South Korean population is estimated as a little short of 52 million, and it was a PG-13 movie, hence, that is the equivalent of one third of the entire Korean population who went to see the movie.

The movie is based on a webtoon series by Joo Ho-min with the same title, Sin gwa hamkke (Along with the Gods). The fantasy drama was serialized in Naver Webtoon from January 2010 to August 2012. 8 A wide variety of traditional Korean deities and underworld guardians escorting the souls of the deceased appear in the comics. It portrays the seven hells, where the soul of a person who has done many wrongdoings would be punished with matching punishments, and unfolds the heart-wrenching stories of ordinary human beings, which are portrayed in greater depth in the original webcomics than in the film. 9 The author of this work, Joo Ho-min, won the President Award in the Comics section of the 2011 Korea Content Award, and is widely loved as one of the major webcomics artists representing Korea. As demonstrated above, in the case of Korea, the discourse of “return of myths” in the late 20th century was followed by a rapid increase of public interest in fantasy and mythical genres partly influenced by the global trends, including interest in ancient Greek mythologies. This trend has subsequently expanded to public fascination with Korean mythology and legends, which brings us to the current situation.

“Neo-mythologism” and “mythologism” in China

In terms of contemporary utilization of myths, China displays more complicated aspects. First of all, it was when the sensation of fantasy genre reached its peak in the 21st century that the notion of “neo-mythologism” 10 appeared in Chinese mythological circles. What served as a decisive opportunity would be the “rewriting myths” project launched by a Scottish publisher, Canongate Books called the Canongate Myth Series. This was a project conceived by Jamie Byng, the lead editor of Canongate Books, to “have the best writers in the world reimagine and rewrite myths by selecting any ancient myths from various cultures and retelling them in any way they want.” It was an ambitious project to create a masterpiece series that could be read for the next hundred years. Canongate signed contracts with world-renowned writers such as Karen Armstrong, Margaret Atwood, Orhan Pamuk, Isabel Allende, Toni Morrison, and the like, to have their works translated and published simultaneously by multiple outlets in 31 countries. According to the original plan, one hundred books were to be published by March 15, 2038, but it is questionable whether the titles published thus far have all measured up to the expectation. There are indeed more than a few great ones like Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad, based on the Odyssey.

Famous Chinese writers such as Li Rui(李銳), Su Tong (蘇童), Ye Zhaoyan (葉兆言), and A Lai (阿來) have also participated in this series. When the Chinese translation of this series’ first title, Karen Armstrong’s A Short History of Myth came out in 2005, the President of the Chinese Society of Mythology Ye Shuxian (葉舒憲) used the term “neo-mythologism (新神話主義)” for the first time in his paper. While “neo-mythologism” is in fact not a completely unfamiliar term in film, music, or literary criticism, Ye Shuxian describes it as “a trend of large-scale revival of myths and fantasies that emerged in the global literary world and art world in the late 20th century.” 11

His view is in line with the aforementioned perspective of Jeong Jaeseo’s “return of myths.” Ye Shuxian constructs neo-mythologism from sources as diverse as novels, films, TV shows, and video games. He attempts to locate “primitive, spiritual, Eastern, and feminist values” in the cultural trend of “neo-mythologism.” This series of values targeted “contemporariness, materialism, Western-centrism, and androcentrism.” 12 However, the Canongate myth series written by Chinese writers for which he had high hopes apparently registered as a disappointment. When Ye Zhaoyan’s HouYi came out, based on the tale of Yi, the heroic archer god who saved people from suffering by shooting down nine suns with arrows when ten suns rose in the sky, Ye Shuxian criticized it harshly by saying that no mythical insight could be drawn from the work. In truth, Ye Shuxian’s examples of “neo-mythologism” remained quite diverse. The aforementioned Canongate Myth series or the Hollywood movie, Troy, directly taken from the existing mythologies were mentioned of course, but he goes so far as to include The Lord of The Rings and Harry Potter series, Avatar, Star Wars, Matrix, as well as the New Age literature such as The Celestine Prophecy, and even films like the Spiderman, Shrek, Dances with Wolves, and The Da Vinci Code. It was so extensive that it almost verged on blurring the definition and scope of what constitutes a myth.

Subsequently, in the mid-2010s, Yang Lihui’s idea of “mythologism” gained influence. 13 Yang focuses on the utilization of “traditional mythological narratives” in a stricter sense of the word and the form, in which they were transmitted in today’s world. Yang’s object of study includes tour guides’ narrations, animations, and TV shows and role-playing games that use ancient Chinese myths. According to her, “mythologism” is the manner in which myth has been removed from the context of daily lives of a local community, the original loci of the myths, and is transferred to a new context to bestow new function and meanings as it unfolds before a different audience. What is interesting about the examples Yang brought up as the case of “mythologism” is that they mostly focused on the contemporary utilization of Chinese myths, unlike Ye’s neo-mythologism. The examples include the case of Wahuang Palace, which is a tourist site of cultural remains associated with Chinese mythology; animations like 5,000 Years of Chinese History: Little Taiji; role-playing games such as The Legend of Sword and Fairy. As such, the examples of “mythologism” that Yang uses as subjects of research are the ones that were based on Chinese myths and legends. As was the case in Korea, the public’s interest in Chinese myths has grown since the 21st century, leading to further utilization of the myths unique to China in culture and tourism industries. Moreover, this development in China is unprecedented anywhere in the word, and the causes and the methods of execution are also diverse and complex. Hence, to understand the underlying cause behind the utilization of traditional Chinese myths in contemporary culture industry, more diverse contexts need to be explored.

First of all, China is one of the countries that the government intervenes in the overall culture industry quite vigorously. The Chinese government not only provides financial, institutional and other types of support to the industry, but also actively intervenes in the planning, production, and circulation stages of any culture industry product. Government support for the promotion of art and culture can certainly be helpful, but the intervention or censorship in the production stage may lead to the side effect of restricting the freedom and constraining the creativity of the creators. In that sense, government intervention is a double-edged sword. Having said this, it should be noted that, at least in China, government intervention seems to have encouraged the myth utilization further.

For instance, 5,000 Years of Chinese History: Little Taiji is an animated TV series that aired on CCTV from October 1999 in China. According to what Yang Lihui mentioned in her paper, numerous children in China learned Chinese myths through this series at the time it aired. It consists of a total of 14 episodes, in which a child called Dalong, a bird called Jingwei, a character that appears in Chinese mythology, and a fairy called Little Taiji travel back in time to the mythical era and meet deities such as Nüwa, Shennong, HouYi and Kuafu in each episode. The series is said to have been wildly popular among children at the time. 14

Yet, the organization which produced this animation is the Committee of Cartoon Protect for Promoting Chinese 5000-Year-Old Culture (CCPC). This committee is an organization established in 1993, when the China Federation of Literary and Art Circles officially registered it under the Ministry of Civil Affairs of the PRC (People’s Republic of China). The purpose for establishing this committee was “to promote Chinese national culture by developing domestic animation industry unique to China, and to enhance the cohesiveness and creativity of the Chinese nation by making traditional culture flourish. . . based on the unique, long-standing, radiant culture of the Chinese nation.” 15

Ever since 5,000 Years of Chinese History: Little Taij (1999) aired and even into the 21st century, China’s culture industry has been utilizing Chinese mythology arduously. The story of the Taoist protection deity, Nezha was transformed into a 52-episode animated TV series called The Legend of Nezha (哪吒傳奇) in 2003, and an animated film called Nezha (哪吒之魔童降世) in 2019, which remains the highest-grossing animated film in China. There is also an animated film called Little Door Gods (2016), based on the myth of Chinese Door Gods called Shentu (神荼) and Yulei (鬱壘).

Within the explosively expanded online literature market in the 21 st century China, 16 fantasy, palace-fighting, tomb-raiding, conspiracy, and romance genres are dominant. The online literature that did well would not only be published in printed books, but also be produced as films or TV series, showing the intermedial mobility. Tang Qi’s Three Lives series is a case in point. In particular, To the Sky Kingdom, whose original Chinese title means “The Peach Blossom of the Three Lives” (三生三世十里桃花) (2009), the first installment of this series, is a fantasy fiction that borrows the mythical worldview and a number of subject matters from Classic of Mountains and Seas (山海經), an ancient book and a rich reservoir of Chinese mythology, combining the Buddhist idea of causation and reincarnation and the Taoist idea of the immortals. This novel was an instant success and was turned into a 58-episode TV series and a romantic fantasy film in 2017. Also, when a role-playing game such as The Legend of Sword and Fairy (仙劍奇俠傳) became a great success, it has also been produced as a TV series. Through these examples, we can see that Chinese myths are actively utilized in contemporary China through various new media including digital media. Yet, there is something more to creating these contents that use fantasy genre or mythology in popular media or creative works than them being a global trend. First, mythology as a genre corresponds well with the China’s government policy to reinforce a sense of identity in the Chinese people and reinvigorate traditional culture. Also, from the perspective of the creators, the fantasy genre based on mythical worldviews is relatively free from government censorship rather than the works that use reality-based social conditions and lives as subject matter. This partly explains the popularity of the fantasy genre such as Three Lives among the Chinese popular consumers.

“Landscaping” of Myth Resources in China

One of the most unique characteristics of China’s contemporary utilization of ancient myths is the prevalence of the so-called “landscaping,” referring to the construction of parks and tourist complexes based on various myths. In China, creating large-scale monuments commemorating mythical figures or legendary kings and emperors have become extremely popular over the last 20 to 30 years. Some examples are as follows:

First is the sculpture of Emperors Yan and Huang(炎黃二帝像) in Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan province, which is a monument that was carved out of a mountain on the Yellow River. The overall height of the monument is 106 meters (348 feet). They depict two of the earliest legendary Chinese emperors, Yan Di and Huang Di. As is known, “descendants of Yan and Huang” (炎黄子孙) is a referent to the Chinese ethnocultural identity allegedly based on a common ancestry associated with a mythological origin. The sculpture was completed in 2007 and was designed to be about 8 meters taller than the Statue of Liberty in New York.

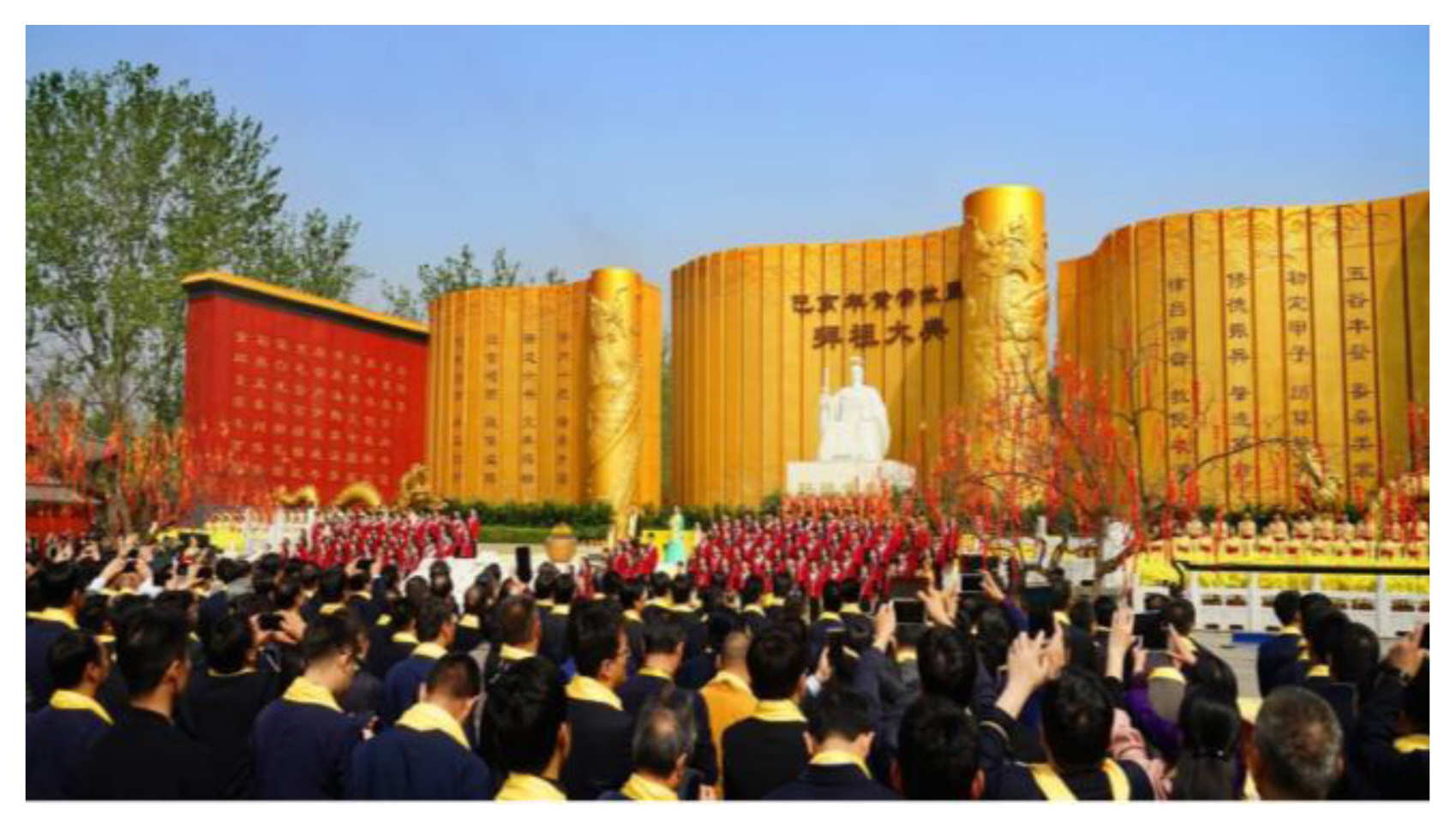

In Xinzheng city in Zhengzhou, there is Huangdi’s Hometown Scenic Spot called Huangdi Guli (黃帝故里). Since 1992, the Cultural Festival for Emperors Yan and Huang has been held here, which was elevated to a grand ceremony called Baizu Dadian (拜祖大典) to worship the Huang-di, or the Yellow Emperor, on a national level, after being approved by the Central Committee of the CPC (Communist Party of China) and the State Council of the PRC (People’s Republic of China) in 2006. This ceremony which is held on the third day of third lunar month every year is broadcast live on CCTV and the internet; and eight thousand Chinese people from more than 20 countries participated in the ceremony celebrating its tenth anniversary in 2015. As the slogan for the ceremony, “same root, same ancestor, and same origin” indicates, it had the objective of contributing to the completion of the “China Dream,” which is the great revival of the nation, by reinforcing the cohesiveness of the Chinese people across the globe. This grand ceremony, Baizu Dadian ( fig. 1.) has become a sort of platform that brings in large investment and immense economic gain, through which tourism has also developed. This annual ceremony was listed as national intangible cultural heritage in 2008 with the approval from the State Council. 17

In front of Kuaiji Mountain in Shaoxing, Zhejiang, stands the Great Yu Mausoleum (大禹陵). Dayu or Yu the Great is known to have prevented floods by controlling water flows and have founded the Xia dynasty. The story of Dayu is one of the representative flood myths of China. This Great Yu Mausoleum has an extremely long history. There is a record that Qin Shi Huang held an ancestral ceremony worshipping Dayu at the Kuaiji Mountain in 210 BCE, and Liang Wudi (梁 武帝) of the Southern Dynasties (南朝, 420–589) built a shrine for Dayu in the 6th century. However, it was not until the former General Secretary of the CCP, Jiang Zemin (江澤民) visited this place, praised Dayu’s spirit highly, and authored the plaque that reads the Great Yu Mausoleum that the Mausoleum drew much attention and became widely known to the world. Since then, the city government of Shaoxing has been holding a public memorial ceremony on every guyu, the traditional great rain day, which generally falls on April 20th. A 21-meter-tall statue of Yu the Great was erected in 2001. The palace was subsequently expanded to incorporate more stone statues and renovated buildings.

In the Yueyang Baling Square (巴陵廣場) by the Dongting Lake in Hunan Province stands a huge sculpture of Hou Yi. According to the myth related to Hou Yi, the Lord Archer, is known to have come down to the earth after shooting down nine suns and eradicated a number of monsters that tormented humans. One of those monsters was a huge snake called Bashe.

However, from the perspective of a mythologist, the most interesting example would be the Dayu Myth Park (大禹神話園) located in Wuhan, Hubei province. Wuhan, is alternately known as Jiangcheng, meaning the river city, because the Hanshui (漢水) and Changjiang (長江) rivers converge there. This river city retains the traumatic memory of about 3,600 people dying due to a great flood in 1998. To respond to the experience of that terrible flood, Wuhan has undertaken an extensive bank revetment project along the shores of Changjiang River from 2000 through 2004 and created a riverside park as part of riverside environment improvement and beautification work. Also, Wuhan New District has been established in this area in 2004, with the Dayu Myth Park an addition to it. It makes sense that for a city frequently struck by the flood damage to have a theme park filled with the sculptures that concretely depict the myth of a great flood-tamer, Dayu.

Yu the Great is said to have travelled across the ancient China, which was referred to as the Nine Provinces, to control the floods. Thus, sculpture, shrines, and temples commemorating him are found in all parts of China. In addition to the Great Yu Mausoleum in Zhejiang, there is also the Dayu Culture and Tourism Complex built in Wenchuan, Sichuan province in 2010. However, what sets the Dayu Myth Park apart from the other places is that from the planning stage, it was established with a clear intention to create a public space depicting the myths surrounding Dayu in sculptural art form, and the scholars in mythology and history, as well as local government enthusiastically participated in the project. There are two reasons that this can be particularly intriguing.

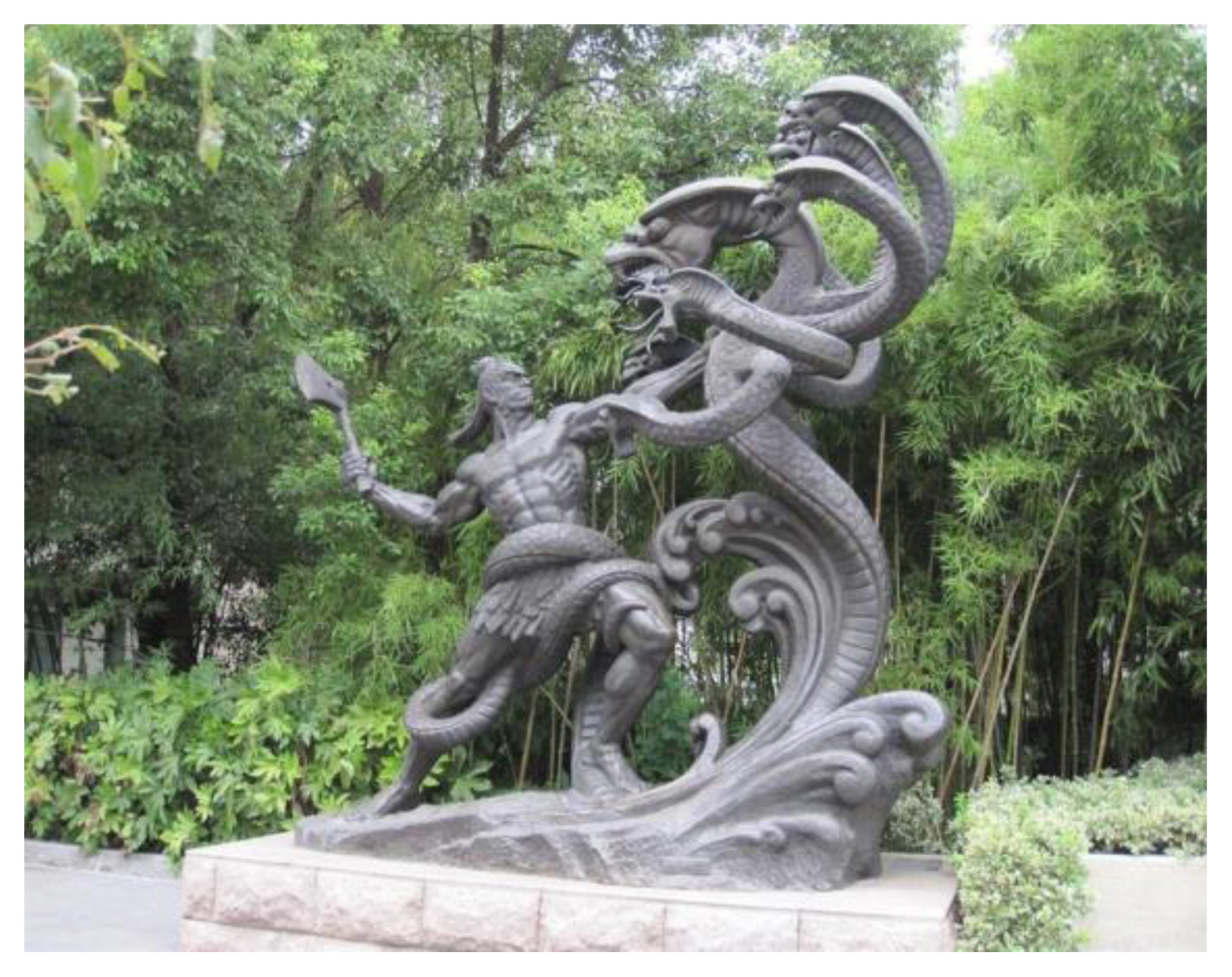

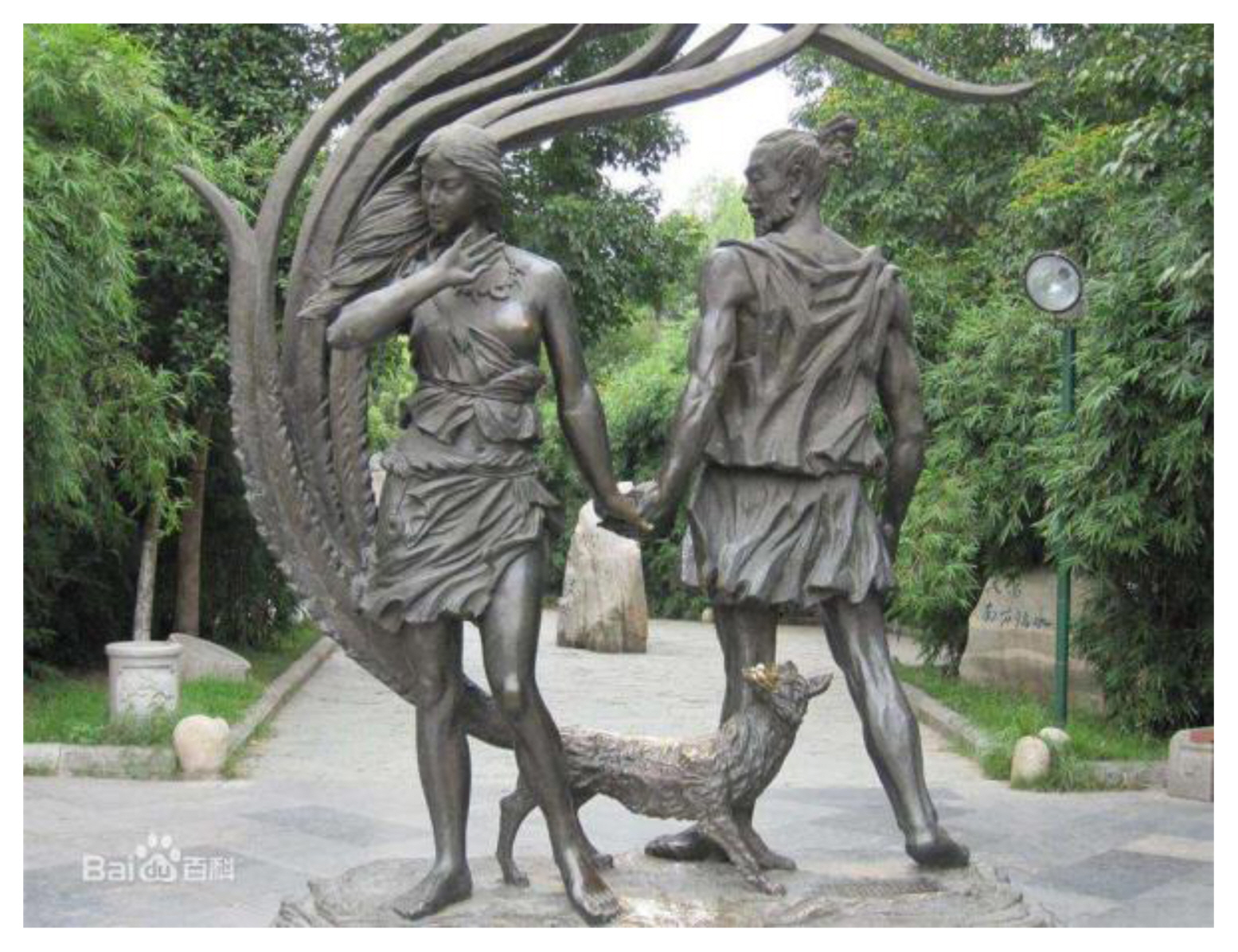

First, throughout Chinese art history, images depicting Dayu are extremely scarce. When the statues of Dayu started to appear around 1980s, the image of the stone-carved pictures of the Wu Liang Shrine (武梁祠) from the Han Dynasty located in Shandong(山東) province, was pretty much the only image that could be used as a reference. A common element found in the images of Dayu created across China is a musi, a traditional wooden hoe ( fig. 2), that he holds in his hand, a tool that he used to control the flood. The Dayu statue in Wu Liang Shrine is of course equipped with the hoe, a trademark that allows us to recognize that the statue is that of Dayu. With so few ancient images as reference sources, creating a sculpture park filled with dozens of statues from Dayu mythology meant that completely new visual representations of Dayu had to be created. Second, in the recent projects dedicated to landscaping the legendary emperors such as the Yellow Emperor, Yao, and Shun, the focus is usually on the “historical value,” and they emphasize these figures as “the great ancestors of the Chinese nation.” In contrast, the Dayu Myth Park deliberately foregrounded “myth” rather than history. For example, the bronze statue below is titled, “Yinglong Draws the Waterways.” ( fig. 3) It portrays a myth that appears in the Songs of Chu (楚辭), a book from the 3rd to 2nd centuries BCE, about a winged dragon called Yinglong that helped Dayu with the control of water by drawing the direction of waterways with its tail. The next statue portrays the scene of Yu the Great killing a monster called Xiangliu.( fig. 4) In the Classic of Mountains and Seas (山海經), Xinagliu is depicted as a monster that “has nine heads with human faces, and the bodies of snake, and consumes what grows on nine mountains.” It is written that wherever Xiangliu went the landscape was transformed into ponds or valleys, which would have been a real headache for Dayu. In the end, Dayu catches and kills Xiangliu. A crucial part of this park is the Nine Tripod Cauldrons Square witha bronze statue of nine tripod cauldrons and Dayu watching them. ( fig. 5) This is based on the story of Yu dividing the Chinese “world” into nine provinces, receiving bronze from the nine territories, and creating ding vessels called the Nine Tripod Cauldrons with the bronze after he successfully tames the flood. As Yu immersed himself in controlling the water, he did not get married until late. And when he met a white nine-tailed fox at Mount Tu, he recognized that it was a sign that he would meet his companion, which, in the end, led him to marry Lady Tushan. This myth is portrayed in a statue, in which the couple who just met have shyly turned their heads in opposite directions while holding each other’s hands and a cute-looking nine-tailed fox holds its head up high as if it is satisfied. ( fig. 6)

The Culture industry, ICH, myth resources

As we have examined so far, there are numerous movements to create grand monuments commemorating mythical heroes of the Chinese nation, turn them into landmarks of the area, and use them as tourist resources by opening a wide variety of festivals and ceremonies. In the Chinese mythology-devoted circle, there is an ongoing discussion, which characterizes recent modes of myth utilization as the “transformation of myth resources.” This is another discourse led by Prof. Yang Lihui after completing her “mythologism” research project. The notion of “myth resources” emerged in China when the culture industry loomed large in the midst of full-scale globalization during the early 21st century. The concept that emerged around this time was “cultural resources.” 18

Chinese traditional culture and folk culture, which was referred to as “Intangible Cultural Heritage” was also considered an important resource for the culture industry. There are a few reasons for this. 19 But a critical one would be that the notion of “intangible cultural heritage” was introduced to China as Kunqu opera was proclaimed as part of UNESCO’s First Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2001, and China officially joined the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2004. In academia, so-called Feiyixue, which could be literally translated as “intangible cultural heritage studies” emerged in China. When “Cultural Heritage Day” was established in 2006, the trend of safeguarding intangible cultural heritage heightened. It was also in 2006 that the term, “myth resource” appeared in Chinese mythological circles for the first time. The discussion of transforming and utilizing myth resources in contemporary society began to shape up. 20 This critical mind produced discourses surrounding the “contemporaneity” of mythology such as “mythologism” or “neo-mythologism,” which led to an even more developed and serious discussion of “creative transformation of myth resources” over the last several years. In the course of examining the modes in which China and Korea utilize myths, I found an interesting difference. In the case of Korea, the government no longer aggressively intervenes in these myth-utilizing projects, either in terms of censorship or for promotion purposes. As for mythical subject matters, they tend to be inclined towards the question of good and evil, or karma and punitive justice, rather than the origin or mythical ancestors of the Korean nation. Also, the content mostly focuses on consoling and encouraging the individuals who live in a stressful contemporary society.

In China, on the other hand, the utilization of myths is much more active, and the support and intervention from the government is also on a much grander scale. That is probably why the landscaping of myth resources which requires long-term investment and large capital is also possible. However, the objective is not simply targeted towards the economic effect that ensues with the development of the culture industry and tourism. In many cases, the purpose is to consolidate the identity of Chinese nation and inculcate among the Chinese population a pride about their traditional cultures. Furthermore, when the government intervenes, the intentions and objectives of the local residents, i. e. the owners of the cultures that the former seeks to promote, are sometimes ignored, which often leads to some negative side effects.

How should we understand the contemporaneity of mythology?

In recent years, we have come across media coverage of the Chinese government’s intensified control on the cultural world. There is a concern that the current trend of utilizing myth as the resource for a nation’s culture industry may lead to the distortion of mythology as well as other negative consequences. It is undeniable that a considerable number of nationalist youths exist in China. However, it is also true that Chinese people’s interests are diverse and the existence of critical discussions actively going on in the new media (including social media) are not well publicized through conventional media.

The same insight holds true for the utilization of myths. It would be too simplistic and hasty to judge that the unprecedented utilization of myths that is taking place in China today is completely created by the state-driven culture industry development project or efforts to strengthen national spirits. In his recent paper, Zhang Duo introduces and analyzes the retelling of myths through various methods including young Chinese people telling myths on their personal media such as Wechat, mobile short clips on DouYin (TikTok), live streaming, and podcast; creating comics or animations based on myths; filming the mythical ceremony on site; and recording the mythological elements in daily lives. 21 While not all of them are necessarily in superb quality, we can find hope and possibility from them, which is a reflection that people are creating something, voluntarily drawing on myth in a forum of new personal media, relatively free from outside intervention. In other words, human imagination and creativity is something that cannot be controlled completely by any institution, and that myth is the oldest form of story created by such human imagination and creativity. Just as generations before us did so in the past, even in this era of the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution, people are still being intrigued and fascinated by the ancient stories and will keep telling them and transmitting them. While the diversified media, that is, today’s digital social media have put us in a situation in which human beings are more subtly controlled and even our individual tastes are transformed into an algorithm, they also create a gap for our creativity and imagination to operate.

It is difficult to say definitively that this particular era that we live in is the one in which the myth has finally returned. It could be an overblown assessment reflecting the hopes of mythologists. However, as it has been described in this paper, it seems apparent that this is not an era in which myths have vanished or died. Therefore, what is required for us may be the belief in possibilities. There is always a possibility for something amazing to be created from the intersection of the power of stories that have stood the test of time, the people who enjoy the stories, new cracks in the life created by emerging new media, and the new imaginations coming from those of us living the present.

Perhaps what is really necessary in understanding the contemporaneity of mythology is humility—humility to realize and admit that, while we believe that we have discovered, dominated, and produced myths, it is in fact the myths, humanity’s oldest stories, that have been drawing us in for such a long time. Only then can we understand comprehensively the peculiarity of myths that keep being reproduced and transformed, as well as the continuity and the vitality of ancient stories that remain in them.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Image of Yu, Stone relief in Wu Liang Shrine

Fig. 3

Yinglong Draws the Waterways

Fig. 4

Yu kills the monster Xiangliu

Fig. 5

Nine tripod cauldrons square

Fig. 6

References

1. An Deming安德明. "Feiwuzhi wenhua yichan baohu: Minsuxue de liangnan xuanze非物質文化遺産保護: 民俗學的兩難選擇." Henan Shehui Kexue河南社會科學 16, no. 1 (2008).

2. Armstrong Karen. Shinhwaŭi Yŏksa. [A Short History of Myth].

Da-hui Lee

. Paju: Munhakdongne, 2005.

3. ChengTaoping程濤平. "DaYu Shenhuayuan jianshe de huiyi大禹神話園建設的回憶." Wuhan Wenshi Ziliao武漢文史資料 11 (2006).

4. Choe Keysook. "About the Multi-layered Communication of Princess Pari on the Webtoon Platform of Daum—Focusing on Analysis of Narrative Structure and Comments [Taejung Sŏsa Yŏn’gu Yŏn’gu]." [Journal of Popular Narrative]. 25, no. 3 (2019): 303–345.

5. Durand Gibert. Sangsangnyŏgŭi Kwahakkwa Ch’ŏrhak. [L’imaginaire].

Jin Hyeong-jun

. Seoul: Sallim, 1997.

6. Feng Tianyu馮天瑜. Shanggu Shenhua Zonghengtan上古神話縱橫談. Shanghai: Shanghai Wenyi chubanshe上海文艺出版社, 1983.

8. baksa Gosari. Kŭk-lak-wang-saeng 極樂往生. 1–4. Paju: Munhakdongne, 2020.

9. Hong Yoonhee. "Chungguk Shinhwajawŏn T’oronŭi hyŏnjuso [Current State of the Discussion on Chinese Myth Resources ]." Chungguk Hakpo [The Journal of Chinese Studies]. 97 (2021): 297–324.

10. Hong Yoonhee. "Chung-kuk sin-hwa-cha-wŏn-ŭi ‘kyŏng-kwanhwa’e tae-han ko-ch’al: u-han tae-u-sin-hwa-kong-wŏn-ŭl il-lye-lo." "Landscapization of Myth Resources in China: In the Case of Dayu Myth Park in Wuhan." Chungguk ŏmunhak nonjip [The Journal of Chinese Language and Literature]. 130 (2021): 355–377.

11. Hong Yoonhee. "21Segi Chungguk Shinhwaŭi Hyŏnjaesŏng Tamnonesŏ Shinhwajawŏnt’ T’oronŭi Paltan [The Beginning of Discussion on “Myth Resources” in the 21st Century Discourse of the “Present-facing” Chinese Mythology]." Chungguk ŏmunhak nonjip [The Journal of Chinese Language and Literature]." 128 (2021): 205–229.

12. Hong Yoonhee. "21-segi Chungguk sinhwahak ŭi hyŏnjae chiyhangsŏng: ‘sinhwajŏggin kŏt’ kwa sinhwa ŭi hwaryong’ sai esŏ [Nowness of Chinese Mythology in the 21st Century: Between ‘the Mythicalness’ and ‘the Appropriation of Myths’ ]." Chungguk ŏmunhak nonjip [The Journal of Chinese Language and Literature]. 113 (2018): 223–247.

13. Hong Yoonhee. "Chunggukshik Shinhwajuŭi Tamnon Ch’urhyŏnŭi Tonginŭrosŏ P’ok’ŭrorijŭmgwa Shinhwajuŭiŭi Tillema [Folklorism as the Driving Force Behind the Emergence of Discourse of Chinese Mytholgism and the Dilemmas of Mythologism, ]." Chungguk sosŏl nonch’ong [The Journal of the Research of Chinese Novels]. 60 (2020): 1–26.

14. Huang Yue黃悅. "Lun dangdai wangluo wenxue dui Zhongguo Shenhua de chuangzaoxing zhuanhua論當代網絡文學對中國神話的創造性轉化." Xibei Minzu Yanjiu 西北民族硏究 103, no. 4 (2019).

15.

Gyeong-ryeol Jang

Hyeong-jun Jin

Jae-seo Jeong

. Sangsangnyŏgiran Muŏshin-ga. [What is Imagination?]. Seoul: Sallim, 1997.

16. Jae-seo Jeong. Dongyangjŏgin kŏsŭi sŭlp’ŭm. [The Sadness of Eastern Things]. Seoul: Sallim, 2006.

17. Joo Ho-min. "Singwa Hamkke : Chŏsŭngp’yŏn." [Along with the Gods: afterlife]. Paju: Anibooks, 2011.

18. Joo Ho-min. Singwa Hamkke : Isŭngp’yŏn. [Along with the Gods: this life]. Paju: Anibooks, 2011.

19. Joo Ho-min. Singwa Hamkke : Shinhwap’yŏn. [Along with the Gods: mythology]. Paju: Anibooks, 2012.

20. Kim Seon-ja. "The Study on the Correlation between the Myth and the Ritual of Huangdi: Since the Establishment of ‘People’s Republic of China’ to the PresentChungguk ŏmunhak nonjip

." The Journal of Chinese Language and Literature. 121:2020, pp 281–313.

21. Liu Xicheng劉錫誠. "Zai zhongxi wenhua bijiao shiye xia kan shenhua ziyuan zhuanhua de zhongguo shijian在中西文化比較視野下看神話資源轉化的中國實踐." Changjiang Daxue Xueba 長江大學學報(社會科學版) 29, no. 3 (2006).

22. Robin Mcneal. "Constructing Myth in Modern China." The Journal of Asian Studies 71, no. 3 (2012).

23. Oh Sejeong. "Musokshinhwa sŏsaŭi tach’ŭngjŏk ihae - iyagit’psaengsŏngt’psot’ongŭi se ch’ŭngwirŭl taesangŭro [The multi-level understanding of Shamanistic myth Princess Bari as a narrative: focusing on levels of story, composition, and communication]." Kihohakyŏn’gu [Semiotic Inquiry]. 54, no. 0 (2018): 119–145.

24. Park Jae-Yeon. "A Study on the Sinpa of Along with the Gods and the Korean Sinpa—Focusing on the comparison between the Sinpa of Singwahamkke Jeoseung and the Sinpa of Along with the Gods: The Two Worlds." Taejung Sŏsa Yŏn’gu [Journal of Popular Narrative]. 26, no. 4 (2020): 77–114.

25. Sun Zhengguo孫正國. "Jihuo rentong: Shenhua ziyuan xiandai zhuanhua de guanjian lujing激活認同: 神話資源現代轉化的關鍵路徑." Changjiang Daxue Xuebao 長江大學學報(社會科學版 42, no. 1 (2019).

26. Sun Zhengguo孫正國. "Quanqiuhua yujing xia kan shenhuaziyuan zhuanhua de liangnan xuanze全球化語境下看神話資源轉化的兩難選擇." Changjiang Daxue Xuebao 長江大學學報 (社會科學版) 29, no. 3 (2006).

27. Sun Zhengguo孫正國. "Wuhan DaYu Shenhuayuan qundiao xushi lunli yanjiu 武漢大禹神話園群雕敍事倫理硏究." Changjiang Daxue Xuebao 長江大學學報 (社會科學版) 43, no. 6 (2020).

28. Yang Lihui 楊利慧. Shenhuazhuyi : Yichan Lüyou yu Dianzi Meiti zhong de Shenhua Nuoyong yu Chonggou 神話主義: 遺產旅遊與電子媒介中的神話挪用與重構, 中國社會科學出版社. 2021.

29. Yang Lihui. "Dangdai Zhongguo dianzi meijie zhong de shenhuazhuyi 當代中國電子媒介中的神話主義." Yunnan Shifan Daxue Xuebao 雲南師範大學學報 (哲學社會科學版) 46, no. 4 (2014).

30. Yang Lihui楊利慧, Zhang Duo 張多. "Shenhua ziyuan chuangzaoxing zhuanhua de tansuo zhi lu神話資源創造性轉化的探索之路." Changjiang Daxue Xuebao 長江大學學報 (社會科學版) 42, no. 1 (2019).

31. Yang Lihui楊利慧. "Yichan lüyou yuing zhong de shenhuazhuyi — yi daoyouci diben yu daoyou de xushi biaoyan wei zhongxin 遺産旅遊語境中的神話主義—以導遊詞底本與導遊的敍事表演爲中心." Minsu Yanjiu 民俗硏究 113, no. 1 (2014).

32. Ye Shuxian. "Bijiao shiye xia de xinshenhuazhuyi — Houxiandai de shenhuaguan — Jianping Shenhua Jianshi 比較視野下的新神話主義—後現代的神話觀——兼評《神話簡史》." Zhongguo Bijiao Wenxue 中國比較文學 66, no. 1 (2007).

33. Ye Shuxian. "Zailun xinshenhuazhuyi — Jianping zhongguo chongshu Shenhua de xueshu queshi qingxiang 再論新神話主義—兼評中國重述神話的學術缺失傾向." Zhongguo Bijiao Wenxue 中國比較文學 69, no. 4 (2007).

34. Ye Shuxian葉舒憲. "“Renleixue xiangxiang yu xinshenhuazhuyi 人類學想象與新神話主義." Wenxue Lilun Qianyan 文學理論前沿. Beijing: Beijing University Press, (2):2005.

35. Zhang Duo張多. "Dangdai Zhongguo shenhua de dazhonghua chonggou—Jiyu xinxing zimeiti dui Shenhua ziyuan zhuanhua de fenxi當代中國神話的大衆化重構—基于新興自媒體對神話資源轉化的分析." Wenhua Yichan文化遺産 2 (2021).

36. Zhang Duo張多. "Douyin li de shenhua: Yidong duanshipin dui Zhongguo shenhua chuantong de chonggou抖音里的神話: 移動短視頻對中國神話傳統的重構." ”, Xibei Minzu Yanjiu西北民族硏究 108, no. 1 (2021).

37. Zhang Juwen張擧文. "Tansuo hulianwang minus yanjiu de xin lingyu 探索互聯網民俗硏究的新領域." Xibei Minzu Yanjiu西北民族硏究 108, no. 1 (2021).

|

|