한국 보수개신교회의 반동성애 담론은 어떻게 프레이밍 되는가? - 도덕적 권위의 변천을 중심으로

국문초록

본 연구는 최근 한국 보수개신교회 내에서 중요한 아젠다로 등장하고 있는 동성애 운동(LGBT movement)에 대항하여 기독교 각계 각층의 리더들이 단순히 성경(the Scripture)에 대한 직접적인 호소를 뛰어넘어 어떻게 이를 효과적으로 저지하기 위한 담론 프레이밍(discursive framing)을 구사하고 있는지 분석한다. 이를 위해 한국의 기독언론매체인 기독신문(Kidok Sinmun)에 기고된 열린 논평(op-ed)들의 콘텐츠 분석을 통해 반동성애 전문가 집단(professionals)이 자신들의 입장을 정당화 하기 위해 동원하는 도덕적 권위와 윤리적 토대의 변천과정을 통시적(1998-2020)으로 추적하였다. 그 결과 정권의 이념적 성향에 따라 이들이 대중적으로 호소하는 도덕적 권위의 유형에 차이가 있음을 발견할 수 있었다. 진보 정권인 노무현, 문재인 행정부 하에서는 동성애 인권을 대한민국의 자유 민주주의와 헌법적 질서에 대한 “실존적 위협(existential threat)”과 연결 짓는 담론적 전략들이 상대적으로 더 자주 동원되었다. 보수 정권인 이명박, 박근혜 행정부 아래에서는 국가 안보나 군사적 방위태세 등과 같은 키워드들이 반동성애 운동을 떠받치는 규범으로서 상대적으로 더 많이 언급되었다. 반면 과학이나 가족의 가치(family value)와 같은 키워드들은 정권의 성향과 관계없이 그 활용 횟수가 점차적으로 증가하였다. 특히 미국의 연방정부 차원에서 동성결혼이 합법화된 2015년을 기점으로 미국과 영국 등을 위시한 서구의 반동성애 엘리트 전문가들이 한국 보수개신교회 내외부의 담론 지형을 형성하는데 지속적인 영향을 미치고 있음을 시론적으로 확인할 수 있었다.

주제어: 반동성애 운동, 도덕적 권위, 보수개신교회, 한국

Abstract

This paper reports on content analysis of the Korean Christian newspaper Kidok Sinmun (1998-2020) with regard to how conservative evangelical elites (CEs) change their discursive resources to construct persuasive appeals against the global LGBT movement. Our findings demonstrate that the CEs focus on different sources of moral authority in response to changing political ideologies of the Korean government or regardless of such ideologies (scientific research, family value). During the progressive Roh Moo-hyun and Moon Jae-in administrations, discursive tactics linked LGBT rights with the existential threat to liberal democracy or constitutional value, while the key words such as national security or military discipline were more frequently employed under the conservative Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye governments. Moreover, experiences shared by the transnational network of Christian activists appear to influence the construction of local perceptions on homosexuality.

KeyWords: Anti-LGBT Movement, Moral Authority, Conservative Evangelicals, South Korea

The anti-LGBT movement in South Korea: History, issues, and discursive strategies

On June 1, 2019, two confrontational rallies occurred at the same time around Seoul City Square, South Korea. On one side, the 20 th Seoul Queer Culture Festival was attended by approximately 150,000 individuals in solidarity with other worldwide LGBT movements. 1 Only a few meters away from the festival’s parade route, Christian groups gathered to argue for the potential harms of homosexuality and the importance of inalienable values of “natural family” as an essential basic unit of society. 2 Not surprisingly, the second group was supported by right-wing grassroots groups waving the national flag of South Korea, linking the threat of LGBT movement with secular, liberal challenges to the Christian foundation of the country. In parallel to Queer Culture Festival attendees, counter-protesters demonstrated their own solidarity with the transnational anti-LGBT movement by means of the prominent display of US flags and English-language banners that had slogans such as, “Homosexuality is sin! Return to Jesus!” 3 The conflict was merely one of the examples of the involvement of evangelicals in the construction of anti-LGBT activism at both the national and international level. Although the Korean public’s perceptions and changing attitudes on sexual minorities have been comparatively well-documented, the trajectory of the anti-LGBT movement and its accompanying practices have not been analyzed in depth. The anti-gay concerns and the associated backlash in South Korea emerged in the late 1990s with the introduction of Japanese animated comics, 4 the subsequent first coming out of a gay celebrity (홍석천, Hong Sŏkch’ŏn) in 2000 5 and the recognition of a highprofile transgender entertainer (하리수, Harisu) by the Korean court in 2002. 6 The events of 1990s and early 2000s stirred conservative evangelical elites (CEs) to raise alarms about the new liberal trends in the society. In 2007, CEs actively and openly opposed efforts to establish a pro-LGBT measure by the left-leaning Roh Moo-hyun administration, 7 which attempted to expand the existing legal framework on human rights protection following the enactment of the National Human Rights Commission Act 2001 – which established “sexual orientation” as one of the grounds constituting a “discriminatory act violating the equal right.” 8 In response, the Assembly of Scientists Against Embryonic Cloning (배아복제를 반대하는 과학자 모임) made an opposing public statement signed by 229 professors from 33 universities nationwide, which was sent to the government and other major parties. 9 The statement argued that should the bill become law, it would “bring about pathological results for the society, such as the decrease in marriage rate, low fertility, and the transmission of AIDS.” 10

The intensity of the anti-LGBT mobilization continued to rise under right-wing governments. In 2010, the Ministry of Justice under the right-leaning Lee Myung-bak administration initiated a new task force for the execution of the anti-discrimination law. In response, conservative grassroots organizations including the Professors’ Alliance for Proper Education (바른 교육을 위한 교수연합) and the Patriotic Parents’ Association (나라사랑학부모회) published a provocative full-page Korean-language advertisement in the October 8, 2010 issue of the Christian Kukmin Daily [국민일보]. It asserted the following consequences of passing the new legislation: 1) legal penalties for uttering the phrase “homosexuality is sinful,” including both imprisonment and fines; 2) installation of gay pastors in all churches; and 3) a rapid rise in homosexuality among adolescents. Subsequently on October 29, 2010, the Kukmin Daily covered a feature article from the first-ever conference at the National Assembly on the Counteraction Against the Establishment of Anti-Discrimination Law. During the event, the leader of bipartisan Congressional Mission Alliance (의회선교연합) expressed that “although it’s undeniable that the basic human rights and diversity of every person should be respected, if [homosexuality] ails our community and goes against common sense and truth, we should resolutely correct it.” In its reply to open inquiries from Solidarity for the Establishment of Anti-Discrimination Law (차별금지법제정연대) regarding the delay in pressing ahead with anti-discrimination bills, the Ministry of Justice replied that “if the concerns surrounding the social and economic burdens following from the establishment of [the law] continue to be raised, the process of institutionalizing the protection by reaching a social consensus might be challenging.” 11

At the same time, independent of actions taken by the administration, center-progressive members of the National Assembly proposed their own anti-discrimination bills protecting the LGBT community in 2008, 2012, 2013 and – most recently – 2020, which have consistently received serious opposition from grassroots CE organizations. When the 2013 bill gained support from 66 out of 300 members of the National Assembly in March 2013, seven Christian Right organizations issued an opposing joint statement and publicized the name, contact, district, and party alliances of each sponsor in four major daily newspapers ( Cho-sun, Joong-Ang, Dong-a and Kukmin). The statement encouraged the readers to petition members of the Legislation and Judiciary Committee to prevent introduction of the bill. During the legislative notice period (March 26 –April 9), 106,643 online comments were posted on the opinion section of the National Assembly’s webpage, almost all of which strongly opposed the proposed bill. 12 Eventually, the bill was scrapped at the end of the 19 th National Assembly’s four-year term in 2016. As contentious as the struggles over the legislative efforts have been, Korean courts have also come under scrutiny for their decisions on the rights of gay people. For instance, in June 2010 the Constitutional Court reviewed the legality of Article 92(6) of the Military Criminal Act which prohibited same-sex sexual acts from being performed in and outside the military barracks, including during leave. In the following year, the Court followed its previous decision from 2002 in upholding the Act by claiming that it did not violate constitutional rights to sexual self-determination, privacy, or personal liberty against the principle of proportionality, and that public interests of ‘establishing healthy living and discipline in the military’s communal society’ and ‘national security’ could not be outweighed by such restrictions. 13 In total, the Constitutional Court upheld the Act three times – in 2002, 2011, and mostly recently in 2016. In 2010 the involvement of the grassroots CEs in the debate continued, when on November 10 the Chosun Daily published an open letter directly addressed to “the Honorable President Lee, the Minister of Justice, the Constitutional Court Justices, the National Assembly Members, and the CEO of the Seoul Broadcasting System” from Mr. Kim, the ex-gay who proclaimed to have successfully “overcome” homosexuality after four years of willingly undertaken treatments. 14 The open letter, suggestively titled “Secrets about Homosexuality that Gays Don’t ever Tell You,” argued that the possible danger of anal sex would be prevalent if homosexual practices were permitted in the military given the hierarchy of the military system. The letter also referenced 1,021 successful conversion cases following therapy in the United States and claimed that grassroots lobbying of US pro-gay activists in the 1970s eventually led to homosexuality being delisted as a mental disorder in the second edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-II) by the American Psychiatric Association. As demonstrated by the following analysis, this rhetoric of dangerous, political homosexuality has not only been frequently adopted but also heavily foregrounded for the purpose of recontextualization by Korean conservative evangelicals as one of their discursive tools to criticize the scientific veracity of the LGBT movement in public debate.

The Role of Religion and the Politics of Sexuality

Religious affiliations, political attitudes, and views of the LGBT community are commonly found to be intertwined. In Korea, Protestants are more politically conservative and less tolerant of opposing political views than their Buddhist and Catholic counterparts 15 and express more anti-LGBT attitudes. 16 The strength of religious attachment also influences anti-LGBT attitudes; in a cross-national study with data from 55 countries, Janssen and Scheepers find that greater religiosity corresponds to more anti-LGBT attitudes, particularly for those holding more traditional beliefs about gender and more authoritarian attitudes. 17

Numerous studies illustrate the role of moral authority in constructing anti-LGBT views and discourse among religious conservatives. Whitehead and Baker investigated the extent to which the legitimized sources of epistemic and moral authority influence the views of Americans towards homosexuality, showing that perceived sources of transcendental order (including religious ones) are intimately associated with views about the cause of homosexuality. 18 In their examination of the Korean evangelical media, Yi et al. identified two narratives of Christian evangelicals relative to the gay community: a) the victim narrative, which posits that the expansion of the LGBT rights endangers religious liberties; and b) the empathy narrative, which encourages personal dialogues between gay and non-gay Christians. 19 Similarly, Reijven et al. find evidence that evangelical elites create a shared discourse to challenge mainstream political ideas, positioning themselves as oppressed and marginalized within the larger public sphere as a tactic to negotiate negative publicity. Shifts in the political climate over time, which affect the ability of CEs to situate themselves in the discursive arrangements relative to opposition groups, further create pressure to make more fundamental shifts in their anti-LGBT argument and the moral authorities upon which it rests. 20

Studies have also illustrated the influence of culturally specific values about the role of family on the discourse of LGBT rights. Lee argues that the globalized human rights approach to justifying the LGBT movement conflicts with traditional Asian values across Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore. 21 Similarly, Kim and Cho describe heteronormative values as deeply engrained in Korean political and educational institutions and thus in Korean national identity. As a consequence of the powerful role of the Korean heterosexual family as “the seat of national belonging,” they claim that most members of the Korean LGBT community eschew political engagement in part because coming out is “difficult, if not impossible.” 22 However, globalization appears to mediate the relationship between religion and anti-LGBT beliefs. In a small interview study of female Korean evangelicals with overseas educational or career experiences, their anti-LGBT beliefs were found to be milder than those of their Korean evangelical counterparts lacking transnational experience, due to the former’s greater exposure to liberal pluralistic ideas and greater likelihood of having LGBT friends and acquaintances. 23

Taken as a whole, these findings lend support to the possibility of recasting James D. Hunter’s ‘culture wars’ thesis in the context of South Korea. Hunter describes the religious underpinnings of contemporary American political discourse as a result of individuals being motivated either by an impulse towards orthodoxy or an impulse towards progressivism. Individuals who exhibit the impulse towards orthodoxy tend to support moral arguments with reference to sources which are “external, definable, and transcendent” and pursue “a consistent, unchangeable measure of value, purpose, goodness, and identity.” Typically, such sources are believed to have originated from divine forces, being revealed through scripture, tradition, and religious teachings. Since the impulses towards orthodoxy or progressivism strongly inform political debate, and these impulses are understood to be intractable, Hunter surmises that the dominant tendency of political discourse is a growing discrepancy between opposing positions over time. 24

However, Hunter’s insistence on a widespread ‘bifurcation’ of religious and political attitudes may not adequately capture the diversity and nuances of moral stances within groups on either side of the orthodox/progressive divide. In their study of moral reasoning about homosexuality amongst American CEs, Thomas and Olson modify Hunter’s concepts of opposing and discrete impulses towards orthodoxy and progressivism, conceptualizing these impulses instead as two poles of a continuum. Through qualitative content analysis of writings published by Christianity Today (a popular American evangelical magazine) over a 50-year period, Thomas and Olson demonstrate that American CEs shifted their moral reasoning in response to growing public acceptance of LGBT rights by reducing their reliance on biblical authority, displaying more tolerant attitudes towards LGBT individuals, and increasingly refraining from condemnations of their opponents’ personal morality. They conclude that, contra Hunter’s prediction of a deepening entrenchment of contentious ‘culture war’ narratives, American CEs had increasingly been shifting toward less orthodox sources of moral justification (e.g., science, natural law) along with the Scripture although their orthodox religious position (i.e., opposition to homosexuality) over this period still remained fundamentally intact. 25

In expanding the literature in this area, we adopt the methodological and theoretical framework devised by Thomas and Olson to delve into the discursive configurations surrounding anti-LGBT movement in South Korea, albeit on a smaller scale and particularly with a primary focus on the deploying of moral authority among CEs. The conceptual apparatus of the present article is strongly connected with their basic assumptions about the continuum of “polarizing impulses” across a range of positions between (or within) orthodox and progressive views on moral authority. Furthering their convention, a particular emphasis is placed on the discursive tactics of such religious actors, as well as the manner in which Christian elites and thinkers may alter their moral justifications in response to the prevailing environments - including government ideologies. Lastly, this study attempts to show specifically to what varying degrees, scales, and intensities the conservative evangelicals in South Korea are engaging in a LGBT-related global culture war through the formation and dissemination of contextualized moral language.

Data & Methodology

Data for the present study were collected from the publicly accessible web archives of Kidok Sinmun (기독신문, http://www.kidok.com), a Korean-language Christian media outlet headquartered in Seoul, South Korea. Founded in 1965, Kidok Sinmun serves as the official newspaper of the largest Protestant denomination in Korea, HapDong Presbyterian Church (est. 1959). Kidok Sinmun was selected twice (2008 (2010) as the most influential Christian newspaper in Korea by Sisa Journal (a Seoul-based current affairs journal) based on its being one of the most widely read circulations of its kind. Moreover, as Kidok Sinmun provides a platform for Christian public figures from across the Korean diaspora, it is appropriate to consider this publication as a part of both the domestic and transnational epistemic communities. As such, Kidok Sinmun articles are well positioned to reveal the prevalent attitudes of Korean Protestant churches towards the LGBT community as they have developed over time and document the emergence and evolution of CE’s moral justification against homosexuality diachronically. The articles published therein are a valuable source of information on how Korean CEs employ variant types of discourses to frame arguments against pro-LGBT measures. Contributors include ministers, professors, lawyers, medical professionals, former governmental officials, and civic advocacy leaders, who tend to legitimize their moral claims with recourse to longstanding credentials. As such, content analysis of the articles in Kidok Sinmun over the course of two decades (1998–2020) sheds light on how CEs attempt to brace themselves for the looming culture war and maintain moral hegemony by recasting their discursive tactics throughout different political administrations.

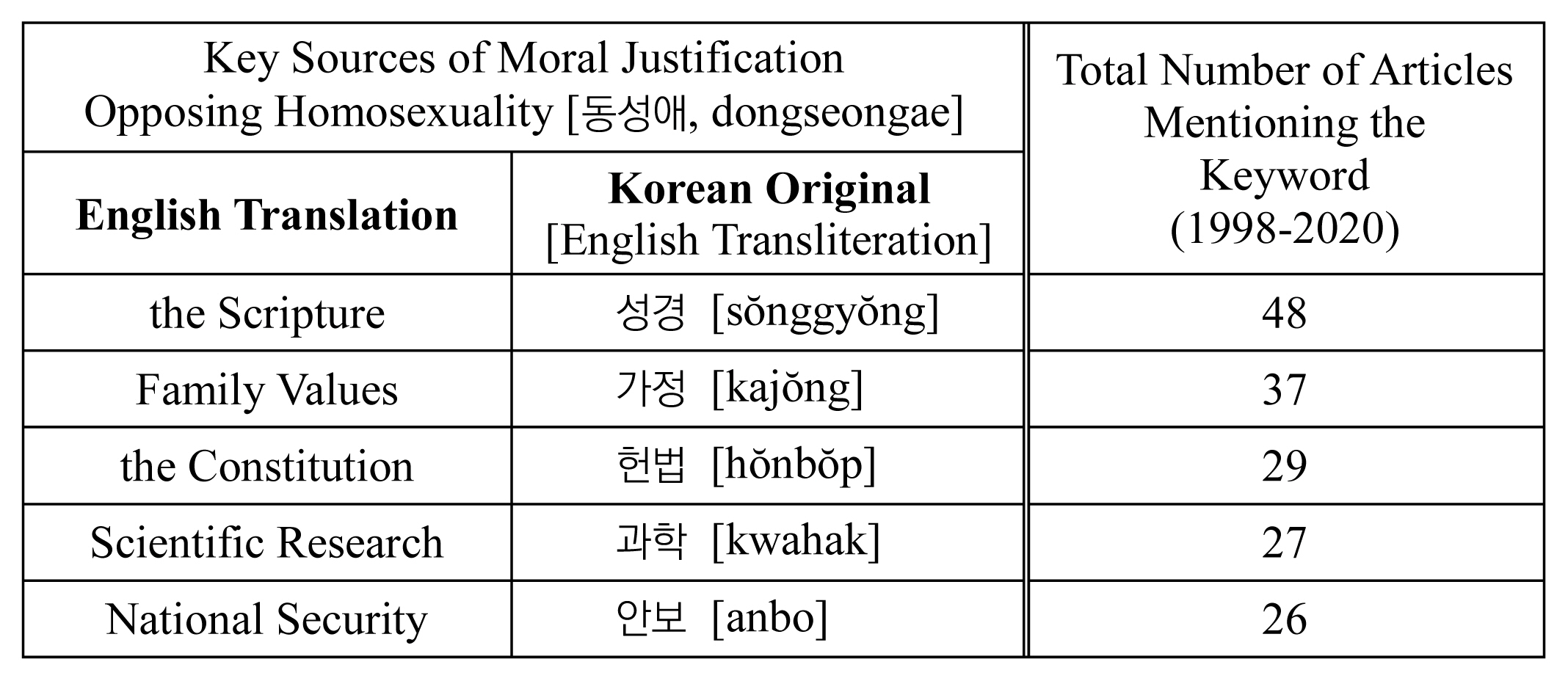

Based on a preliminary review of the articles to determine an appropriate sampling scheme, 26 all articles published in Kidok Sinmun between January 1, 1998 and September 30, 2020 were reviewed for any discussion of the LGBT movement, LGBT community, or LGBT rights. There were two stages in identifying and categorizing articles to be examined. First, a search of the key word “homosexuality (동성애 dongseong-ae)” during our entire sampling frame identified 1,746 articles related to homosexuality. The search function of Kidok Sinmun allowed the identification of subject fields to be categorized into either (open) editorials or feature articles. Articles categorized as open editorials were either explicitly labeled as such or had another indicator which made it clear that the article was unequivocally offering the writer’s normative opinion and/or position statement on the issue of homosexuality (e.g., articles on gender mainstreaming). Feature articles mostly publicized detailed investigations, special coverage, or “experts” interviews on the recent challenges of LGBT groups at home and abroad, along with Christian ways of “understanding the times” which were highlighted by the editors of Kidok Sinmun. After performing a careful reading several times, 96 editorials and 38 feature articles were determined to meaningfully address the topic of homosexuality, for a total of 134 articles. Second, articles were coded based on sources of moral justification that each piece relied on to justify the author’s stance. Those shifting languages could be said to exemplify and represent the normative toolkit which each contributor employed in establishing their own case against the institutional changes or proposed public policies related to LGBT rights, such as the development of anti-discrimination law. They revealed the particularities and nuances of Korean evangelical elites’ situated interpretation as well as offered idiosyncratic insights into their moral reasoning across our sampling period. It could be said that certain words were suggestively linked with the evangelical elites’ personal attitudes on homosexuality and moral reasoning. Figure 1 lists the five key words – in descending order of frequency – which were employed as a fundamental rationale for opposing homosexuality. 27

The articles were further divided into five-year periods, coinciding with the shifts in the South Korean presidential administrations, to assess how evangelical elites changed their discourses depending on the ideology of the current governments. As such, the research dates selected offer a critical window into the last 20 plus years of South Korean evangelical thought on sexual liberalization – a period that closely corresponds with the rise and unfolding of post-material values 28 in South Korea.

The Shifting Conservative Evangelical Discourse, 1998–2020

The distribution of articles over time reveals that the topic of homosexuality becomes gradually more prevalent within the pages of Kidok Sinmun during the period 1998–2020, as shown in Table 1. At their beginning, articles about homosexuality constituted only a small proportion of all articles in the Kidok Sinmun. From 1998 to 2012, articles mentioning homosexuality accounted for less than 1% of all articles published (0.69%, or 481 out of 70,109); while there was a substantial increase in the number and proportion of articles referencing homosexuality in the period from 2013 to 2020 (5.0%, or 1,406 out of 28,217), which encompasses the Park and Moon administrations. Two trends deserve special consideration. First, one can see that the share of KS (open) editorials and feature articles about homosexuality generally increased across the two decades both in number (3 to 35, 2 to 11) and as a percentage (2.04% to 6.27%, 1.36% to 1.97). This suggests that evangelical elites gradually prioritized an intellectual engagement with the issue and might continue to do so in the future. Second, the number of Kidok Sinmun feature articles concerning homosexuality particularly increased during leftwing governments (2003–2007 and 2017–2020). This trend squarely corresponds to the pro-LGBT initiatives taken by each of those administrations. For example, the number of KS feature articles escalated to 8 from 2 in the previous administration around the time the 2007 Anti - discrimination Bill was proposed by the Ministry of Justice (Roh), which included “sexual orientation” as grounds for protection against discrimination. Also, feature articles during our latest sampling period (approximately 3 years, not the full 5-year term of administration) increased to 11 from 9 compared to the preceding government, especially around the time of President Moon’s preliminary announcement of a constitutional amendment which supposedly intended to promote socially constructed “gender equality.”

Key Sources of Moral Justification Opposing Homosexuality

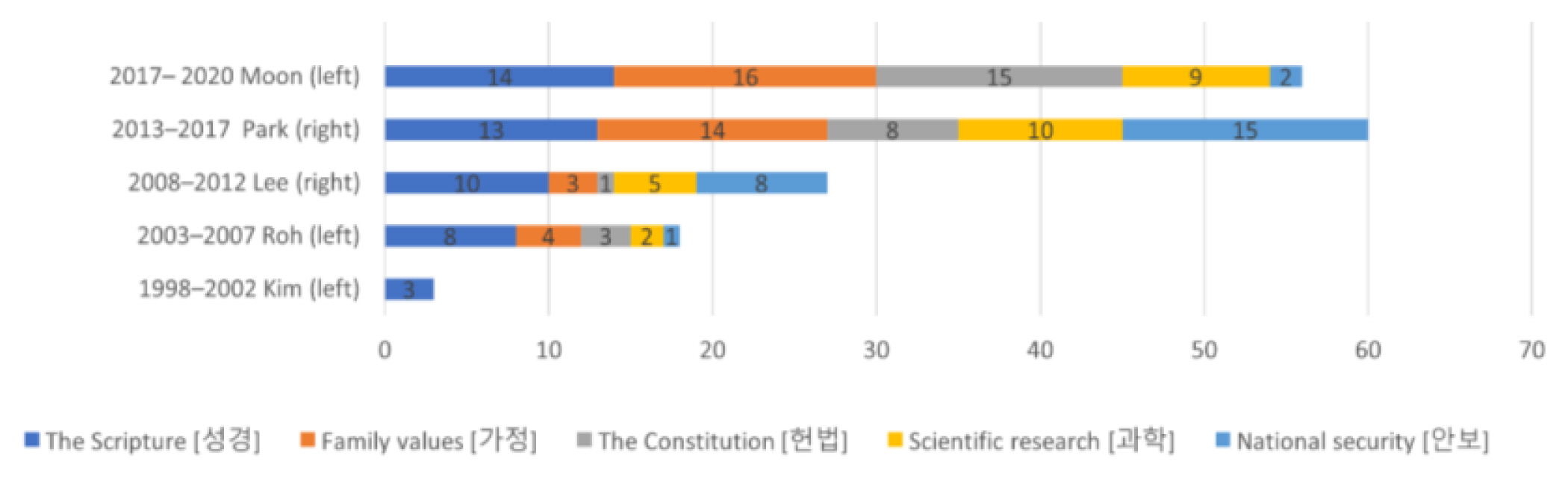

Content analysis revealed five sources of moral justification, namely: 1) the Scripture; 2) family values; 3) the Constitution; 4) scientific research; 5) national security. Figure 2 and Table 2 below both illustrate the frequency with which each moral justification was invoked during respective administration between 1998 and 2020. Our findings demonstrate that Korean CEs have in fact gradually and consistently pluralized their sources of moral authority either in line with the ideologies of the prevailing administrations (national security, the constitution) or regardless of such ideologies (scientific research, family value). Reliance on the Scripture as the key source of moral justification decreased over time in its proportion, gradually transitioning from the dominant justification during the Kim administration (75 % of articles published from 1998–2002) to a relatively downsized recourse during the Moon administration (about 30% of articles published from 2017–2020).

Moral Justification #1: The Scripture

Homosexuality-related editorials and feature articles mentioning the Scripture as a key source of moral justification stressed that specific verses in the Bible (e.g., Genesis 19:1~11, Leviticus 18:22, Judges 19:22~25, Romans 1:26~27) strongly opposed same-sex relations. For example, one article mentioned the following verse from the Bible: “Men committed indecent acts with other men and received in themselves the due penalty for their perversion” (Romans 1:26–27) and suggested that Christians should follow God’s created order which dictates only exclusive male-female relationships to avoid divine damnation. Moreover, the apocalyptic images from biblical stories (e.g., Sodom and Gomorrah) were evoked in some articles as a possible consequence awaiting the country if Christians were silent about the problem. Reliance on the Scripture as a source of moral authority occurred consistently throughout each administration but waned in popularity over time.

Whereas the Scripture was the only moral authority referenced from 1998–2002 (Kim, left), other sources of moral authority were invoked just as frequently as the Scripture during the subsequent administrations; by the time of the Moon administration (2017–2020, left), the appeal to the Scripture was far exceeded by reference to other sources of moral justification combined. There does not appear to be any correspondence between the frequency with which the Scripture was used as moral justification and the political leanings of the administration during which the article was published.

Moral Justification #2: Family Values

Articles mentioning family values as a key source of moral justification focused on how the heteronormative family structure was crucial for the maintenance of healthy social life, especially for children. The authors of those articles typically framed their arguments in vulgarized, simplified terms that spoke to the citizens’ need to ensure the survival of the nation (e.g. “gays cannot give birth”), while arguing that the acceptance of the LBGT movement could lead to the endorsement of other “dysfunctional” forms of sexuality (e.g., pedophiles). Similarly, in terms of thematic genre, we found that evangelical leaders have diversified the cultural sources of their repertoire relevant to family value. As such, the share of western precedents – which they tapped into as a way of warranting compelling narratives and mobilizing rank-and-file audiences – gradually increased:

In Massachusetts, U.S., where the anti-discrimination law had been passed, a father, who refused his 5-year-old son to be educated on same-sex intercourses in kindergarten, was apprehended and sent to prison. In another theater play at a public high school, Noah in his Ark was staged as engaging in sexual intercourse with animals during the Flood; the Magi and the Virgin Mary were depicted as HIV patients and a lesbian respectively. (…) Although Korean American parents were shocked at the content of sex ed, they couldn’t raise any objections because the anti-discrimination law had already been legislated in the state. 29

Table 2 demonstrates that the number of articles relying on family values as a source of moral justification increased consistently regardless of regime types of consecutive administrations. Despite the increase in reliance on this specific justification in more recent regimes (Park administration, 2013–2017; Moon administration, 2017–2020), no correlation can be made with a particular regime type, given that the Park administration was a right-wing regime, and the Moon administration a leftist one.

Moral Justification #3: The Constitution

More recently, homosexuality-related editorials have promoted “the Constitution” as a source of legitimacy for their anti-LGBT practices. They present their claims condemning homosexuality on the grounds of liberal values, such as freedom of speech or religious liberty. Most of those articles selectively draw upon the clauses of the pending (anti-discrimination) bills to bring attention to the anti-liberal characteristics of the proposals. The language of threat and fear is particularly prominent throughout the articles, not least with regard to how the social transformation triggered by the LGBT movement would victimize conservative Christians and oppress their right to worship. One article written during the Moon administration, using the radical changes in Europe during 1960s and Gender Mainstreaming as a point of reference, claimed that the progress of the LGBT movement could fundamentally reshape the constitutional orders in South Korea:

[t]he European New Left [of the 1960s], armed with gender ideology, justified homosexuality on the terms of human rights and used it as a political leverage to eventually enact the same-sex marriage and promote the anti-discrimination law as a means of keeping the mouth of churches shut. … “[s]atisfied with its destructive force, the pro-LGBT alliances are further trying to implement Gender Mainstreaming [GM] as an updated global strategy to achieve world domination. … our churches should remain alert amid this crisis because the threat of GM is now landing on the Korean soil and targeting our legal frameworks. As soon as the creeping idea of GM is implemented in our society, every law - ranging from the Constitution to local ordinances - should be revamped according to their gender perspective. 30

The articles which used this type of rationale as a key source of moral justification are particularly numerous in 2003–2007 (Roh administration, 3 articles, 21.43%) and 2017–2020 (Moon administration, 15 articles, 32.61%). Both periods correspond with left-wing administrations, which demonstrates a tendency of CEs to rely on victimhood narratives in tandem with threat language (e.g., world domination) by way of invoking moral panic against homosexuality during more liberal political eras.

Moral Justification #4: Scientific Research

Some editorials and feature articles mentioned “scientific research” as part of a new discursive shift to oppose homosexuality, emphasizing there was no scientific – especially biological – evidence that it was innate (i.e., the “born this way” justification). The research concluding otherwise was the result of ‘under the radar’ lobbying by pro-LGBT activists. For instance, it was argued that the removal of same-sex attraction from the list of DSM-II illustrates a very rare case of scientists succumbing to a domineering social group rather than scientific facts. The author of one article attacked the scientific evidence in favor of homosexual orientation as having been tainted by the political agenda of the LGBT activists: “there were some academic papers that made people mistakenly believe that homosexuality is innate. (…) These results were introduced through the popular media and subsequently westerners started to get the wrong idea that the same-sex attraction is predetermined by birth.” 31 The same author further claimed that a new body of knowledge debunks the traditionally held myth of pro-LGBT activists and that the mainstream scientific community should be adamant about this:

Since 2000, there was a mass survey on the homosexual orientation of identical twins. Surprisingly, the cases of homosexual correspondence between them were less than 10% of the entire sample. Given the fact that identical twins have the same genetical make-up and are exposed to similar environments throughout their upbringing, such a low rate of match-up supports the scientific discovery that same-sex orientation is culturally acquired. 32

The data indicate that CEs have increasingly resorted to scientific research as moral justification, regardless of the types of regimes prevailing in the country. Since 2008 the number of articles relying on scientific research increased consistently compared to the articles using the same justification published during the previous regimes; this demonstrates a trend prevalent amongst evangelical leaders and thinkers to gradually distance themselves from exclusively religious justifications (e.g., Scripture) and shift the direction of the debate towards the scientific basis of LGBT movements.

Moral Justification #5: National Security

Articles which relied on the protection of national security as a source of justification for the anti-LGBT campaigns argued that the liberalization of sexual norms and the possible spread of HIV/AIDS would inevitability lead to a similar trend in the military, to the detriment of its preparedness against the communist North. For instance, in one article the author applauded the Korean Constitutional Court’s strict ruling reinforcing the prohibition of anal sex in the military in Article 92(6) of the Military Criminal Act with the following words:

I commend the Constitutional Court for the appropriate ruling because it serves as an authoritative milestone that acknowledges the sacrifice and commitment of our sons to maintain strong discipline and that presents the undisputed guidelines of reconciliation on this issue among the people. 33

The key justification was formulated by the author as follows:

[W]hat if people start worrying that ‘my son could be sexually harassed or a victim of anal sex in the barracks’ and become afraid of sending their children to the military? Obviously, there will rise ‘a national protest against the conscription which permits the indecent act.’ 34

By referring to the justification based on the national security argument, the contributors attempted to bring the reader’s attention to the possible negative consequences which could be given rise to by pro-gay social changes, i.e., a lax military discipline and moral corruption that will benefit the North. One full-page newspaper advertisement in major dailies further stated: “the legalization of the sodomy act in the military will only make the Kim family happy.” 35 As shown in Table 2, reliance on national security as a key source of moral justification was particularly prevalent during the right-wing administrations of Lee (2008–2012) and Park (2013–2017).

The Transnational Politics of Family Values and Changing Moral Authority

Notably, the trend of relying on family values and constitutional protection as a ground for legitimacy can be explained by reference to the growing influence of the Western Christian anti-gay activists. They especially helped propagate rights-based language – including parental responsibilities – to make a “rights turn” in Korean CE’s discursive formation. 36 The legalization of same-sex marriage in the United States on 26 June 2015 alerted evangelicals in South Korea to brace for their own battle against similar institutional changes in the country. From that year onwards, Western religious rights advocacy organizations played a crucial role in shaping the ethical outlooks and personal attitudes of their Korean counterparts. Representatives of such organizations offered through media appearances as guest speakers, interviewees, and special panelists the discourses of victimhood (e.g., religious persecution) and the possible consequences of “gender ideology.” They also selectively disseminated particular events or episodes (e.g., the Colorado baker) as symbolizing the potential future of Korean evangelicalism in case the Korean CEs were to yield to the global LGBT movement. This trend was likely to have been facilitated by two recent milestone conferences: the Seoul Global Family Convention (June 1st, 2017) and the 5th Ex-gay Human Rights Forum in Korea (July 4th, 2016), both of which were held at the National Assembly of South Korea with the sponsorship of right-wing lawmakers. Those speakers shared the stories of religious persecution especially after the introduction of pro-LGBT measures in the West, for instance in relation to how Christian parents were being deprived of their right to educate their children on the issue of sexuality according to their religious convictions. One speaker used the following words to describe the predicament:

Our opposition to the cultural revolution in [Germany] has been increasingly criminalized by new laws against newly invented crimes. What are the main fronts of this revolutionary battle? Is it same-sex marriage? The indoctrination and sexualization of children by force of state and now the new wave of transgenderism. 37

One lawyer from the UK encouraged Christians in South Korea to work proactively before it is too late toward starting counter-cultural movement with the support of legal counsel and grassroots advocacy using her litigation cases as an example.

(…) then equality legislation which bans discrimination on the grounds of homosexuality. Treating homosexual practice like the color of our skin. (…) Pastors losing their jobs because of sermons in churches on homosexuality. Street preachers arrested. Purity rings banned from the school. (…) I know every one of these people very well. Our government says, in Europe, the cross is not a Christian symbol. Secular liberal humanism has killed God in our society. 38

Another recalled the operation of Western secular universities which threatened the freedom of Christian students to express their opinions based on religious values:

Even the situation at UC Berkeley, which has been advocating the “Free Speech Movement (FSM)” since 1960s, is not really different… Classes with anti-homosexuality contents are cancelled and anti-gay movements cannot take place due to physical threats against such campaigns. 39

The invited Korean American speakers were eager to call their remnant brethren to action in fighting the pro-LGBT organizations that might become influential in Korea and eventually helping counsel LGBT persons to get proper therapy without any institutional hurdles:

I sincerely pray that our fatherland South Korea does not see the equivalent of ACLU [American Civil Liberties Union] coming into existence in the near future. If that happens, Christian teachers and schools will have to live under constant fear because there will be a wave of anti-discriminatory lawsuits sparked against their beliefs. 40

In this vein, the contributors to the Kidok Sinmun emulated their Western counterparts by stressing how pro-LGBT policies in the West ended up destroying the Christian foundation of its civilization and reminded their audiences that it is time to be united to resist the creeping cultural degeneration. One author who attended one of the above events emphasized that Korean churches were spared up to this day by God for the mission and they should actively embrace their role as the last frontier:

UK churches remained silent all the way when there was a door slightly opening for homosexuality. As a result, Christians there are still reversely discriminated against with no hopes of correcting it. This is not just the UK’s story. We should remember if homosexuality is legalized, Korean churches will fall victim to a similar kind of ordeal. 41

The Ongoing and Future Outlook of Korean Culture Wars

This study examines discursive shifts strategically employed by CEs to frame opposition to LGBT rights across multiple periods of governance. This paper has three key findings related to the discourses in Korea which shape the language of the anti-LGBT movement and sustain the campaign itself. Firstly, we find that despite the stereotype of CEs unilaterally adopting the Scripture as the sole authority, the primary sources of moral justification relied upon by the evangelical elites have been pluralized to better appeal to the ordinary citizenry as well as in-group congregations. In line with the “rights turn” and the “politics of family values” in the US, Korean CEs have most recently turned to constitutional guarantees (e.g., religious freedom, parental rights) for invoking legitimacy with regard to their activism and producing compelling narratives in the eyes of the public. It is particularly noteworthy that over the years the focus of the articles shifted from the traditional theological, orthodox teaching about sexual doctrines to the legally recognized grassroots Christian mobilization. As such, the tone and style of feature articles and editorials published in Kidok Sinmun are increasingly geared towards inspiring rank-and-file audiences to be actively engaged in opposing homosexuality as part of Christian commitment, including influencing public policy debates in favor of the anti-LGBT measures. This explains the evident growing diversification of moral justifications in line with the popularization of conservative sources of the anti-LGBT repertoire and the development of a rights-based argumentation.

Secondly, Korean evangelical leaders and thinkers focus on different sources of moral authority in response to changing political ideologies of the South Korean government. For example, during the progressive Roh and Moon administrations, the discursive tactics of CEs relied to a large extent on key words such as ‘liberal democracy’ and ‘constitutional rights’ as a reactionary trope to the prevailing leftist-liberal climate. This coincides with their post-Cold War discursive formation that “focused on actual or proposed threats to the foundational principles of the Republic of Korea.” 42 In contrast, during the right-wing administrations, CEs portrayed the potential danger of homosexuality through claims based on the preservation of ‘national security’ or ‘defense posture’ (in combination with discussions of the security risk from the communist North) and South Korea’s geopolitical significance of all-time ‘military discipline.’ We also found that the number of articles relying on family values and scientific research as a source of moral justification increased consistently regardless of types of consecutive administrations. The shifting language of the CEs across different administrations could be said to exemplify and represent the kinds of adaptive framings which the CEs purposefully and skillfully employ to establish their case against certain institutional arrangements supporting the LGBT community, such as the Korean anti-discrimination law. Additional research is warranted to determine the extent to which CE’s evolving anti-homosexuality stances — postulated in this paper to be partially affected by prevailing social environments — affect the attitudes of political leadership and non-religious audiences towards broader cultural issues, the future trajectory of anti-LGBT movement in South Korea, or the Kidok Sinmun and its contributors.

Thirdly, the experiences shared by the transnational network of Christian activists serve as an authoritative toolkit in framing local perceptions on homosexuality when justifying the Korean evangelical elites’ Manichean narratives and their corresponding rhetorical devices. In this vein, we found that after the year 2015, Korean evangelical leaders started to instrumentally emulate their Western counterparts by reinventing the general language of fear and threats in a way that could persuasively locate their discursive configuration within the local Christian-LGBT conflict.

However, Korean CEs did not mechanically mimic the discourses of evangelical partners from the West. They also interpreted the emergence of the LGBT rights through the lenses of their unique historical legacies (e.g., colonial past, the Korean War). They creatively imbued particular meanings to their audiences through sense-making schemes which equate the LGBT movement with a menace to Korea’s traditional values or – in some cases – an evil agenda of neo-Marxists complicit in destroying the liberal democracy of South Korea. 43 To fully recontextualize the discourses of the anti-LGBT movement in Korea, one must understand how the religious elites reappropriate the looming challenge of secular advancements through their own hermeneutical underpinnings. It also necessitates a contemplation of the way in which they associate their activism with the reconstruction of conservative forces in the currently leftleaning society. 44 Without recognizing an underlying apparatus of social imaginaries and attendant narratives or genres – such as their unique self-identification as an agent for the unification of the “pure” Korea according to God’s eschatological plan – it is impossible to wholly explicate the right-wing backlash of Christian evangelicals against the liberal tides. At a time of massive social changes in South Korea, the discursive politics of sexuality and the religious knowledge sphere that operates within it are supposedly critical to assessing the future cleavages of Korean society. Thus, conservative evangelical elites’ discursive framings can subsequently be understood as a proxy for the broader normative orientation with regard to similarly divisive cultural issues (e.g., abortion). It remains to be seen to what extent Hunter’s culture war thesis will hold temporally and spatially for non-Western religious actors and whether the increasing progressive impulses within and without churches can portend the liberalization of societal norms and more tolerance towards out-groups.

Acknowledgements

*This article was supported by UCI Center for Asian Studies and UCI Center for Critical Korean Studies. Wondong Lee thanks Wesley Wentworth (IVP Korea), Joseph Yi, and Joe Phillips for their stimulating ideas and the two anonymous reviewers at International Journal of Korean History for their critical feedback on earlier versions of this article.

Figure 1

Keywords of moral authority—English translation and Korean original [English transliteration] and Total Number of Articles Mentioning the Keyword-in descending order of frequency (overlaps included)

Figure 2

Key source of moral justification during different administrations, by frequency of use in editorials and feature articles about homosexuality (overlaps included)

Table 1

KS editorials/op-eds and feature articles about Homosexuality, per presidential period (party ideology)

|

1998–2002 Kim (left) |

2003–2007 Roh (left) |

2008–2012 Lee (right) |

2013–2017 (May 9) Park (right) |

2017 (May 10)–2020(Sep 30) Moon (left) |

Total |

|

Total articles |

24,318 |

24,522 |

21,269 |

16,802 |

11,415 |

98,326 |

|

KS articles mentioning Homosexuality (As % of total articles) |

147 (0.60%) |

193 (0.79%) |

141 (0.66%) |

707 (4.21%) |

558 (4.89%) |

1,746 (1.78%) |

|

KS editorials (op-eds) about Homosexuality [As % of Homosexuality articles] (As % of total articles) |

3 [2.04%] (0.01%) |

6 [3.11%] (0.02%) |

13 [9.22%] (0.06%) |

39 [5.52%] (0.23%) |

35 [6.27%] (0.31%) |

96 [5.50%] (0.10%) |

|

KS feature articles about Homosexuality [As % of Homosexuality articles] (As % of total articles) |

2 [1.36%] (0.01%) |

8 [4.15%] (0.03%) |

8 [5.67%] (0.04%) |

9 [1.27%] (0.05%) |

11 [1.97%] (0.10%) |

38 [2.18%] (0.04%) |

Table 2

Key source of moral justification as % of KS editorials and feature articles about homosexuality

|

1998–2002 Kim (left) |

2003–2007 Roh (left) |

2008–2012 Lee (right) |

2013–2017 (May 9) Park (right) |

2017 (May 10) – 2020 (Sep 30) Moon (left) |

|

KS editorials (op-eds) and feature articles about homosexuality |

5 |

14 |

21 |

48 |

46 |

|

Articles that relied on the Scripture [성경] as a key source of moral justification (As % of KS editorials and feature articles about homosexuality) |

3 [75%] |

8 [57.14%] |

10 [47.62%] |

13 [27.08%] |

14 [30.43%] |

|

Articles that relied on scientific research [과학] as a key source of moral justification (As % of KS editorials and feature articles about homosexuality) |

0 [0%] |

2 [14.29%] |

5 [23.81%] |

10 [20.83%] |

9 [19.57%] |

|

Articles that relied on national security [안보] as a key source of moral justification (As % of KS editorials and feature articles about homosexuality) |

0 [0%] |

1 [7.14%] |

8 [38.10%] |

15 [31.25%] |

2 [4.35%] |

|

Articles that relied on family values [가정] as a key source of moral justification (As % of KS editorials and feature articles about homosexuality) |

0 [0%] |

4 [28.57%] |

3 [14.29%] |

14 [29.17%] |

16 [34.78%] |

|

Articles that relied on the Constitution [헌법] as a key source of moral justification (As % of KS editorials and feature articles about homosexuality) |

0 [0%] |

3 [21.43%] |

1 [4.76%] |

8 [16.67%] |

15 [32.61%] |

References

1. Cho Sarah, Lee Ju-heon. "Waving Israeli Flags at Right-Wing Christian Rallies in South Korea." Journal of Contemporary Asia, Online First Feb; (2020).  2. Lee Won-dong, Phillips Joe, Yi Joseph. "LGBTQ+ Rights in South Korea – East Asia’s ‘Christian’ Country." Australian Journal of Asian Law 20, no. 1 Article 6. (2019).

3. Kim Jung-hyoun. "Religion and Political Attitudes in South Korea." A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree. University of Tennessee, 2006.

4. Rich Timothy S. "Religion and Public Perceptions of Gays and Lesbians in South Korea." Journal of Homosexuality 64, no. 5 (2017).  5. Janssen Dirk-Jan, Scheepers Peer. "How Religiosity Shapes Rejection of Homosexuality Across the Globe." Journal of Homosexuality 66, no. 14 (2019).  6. Whitehead Andrew, Baker Joseph. "Homosexuality, Religion, and Science: Moral Authority and the Persistence of Negative Attitudes." Sociological Inquiry 82, no. 4 (2012).  7. Yi Joseph, Jung Go-woon, Phillips Joe. "Evangelical Christian Discourse in South Korea on the LGBT: the Politics of Cross-Border Learning." Society 54 (2017).  8. Reijven Menno H, Cho Sarah, Matthew Ross, Dori-Hacohen Gonen. "Conspiracy, Religion, and the Public Sphere: The Discourses of Far-Right Counter-publics in the U.S. and South Korea." International Journal of Communication 14 (2020).

9. Lee Po-Han. "LGBT rights versus Asian values: de/re-constructing the universality of human rights." The International Journal of Human Rights 20, no. 7 (2016).  10. Kim Hyun-young, Cho John. "The Korean gay and lesbian movement 1993–2008: from “identity” and “community” to “human rights”." South Korean Social Movements. Shin Gi-wook and Chang Paul eds. London: Routledge, 2011.

11. Jung Go-woon. "Does Transnational Experience Constrain Religiosity? Korean Evangelical Women’s Discourse on LGBT Persons." Religions 7, no. 10 (2016).  12. Hunter James D. Culture Wars: The Struggle To Control The Family, Art, Education, Law, And Politics In America. New York: Basic Books, 1992.

13. Thomas Jeremy N, Olson Daniel VA. "Evangelical Elites’ Changing Responses to Homosexuality 1960–2009." Sociology of Religion 73, no. 3 (2012).  14. Inglehart Ronald. The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles Among Western Publics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977.

15. Dowland Seth. "“Family Values” and the Formation of a Christian Right Agenda." Church History 78, no. 3 (2009).  16. Lewis Andrew R. The Rights Turn in Conservative Christian Politics: How Abortion Transformed the Culture Wars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.  17. Ryu Dae-young. "Political Activities and anti-Communism of Korean Protestant Conservatives in the 2000s." Asian Journal of German and European Studies 2, no. 6 (2017).  18. Cho Kyu-hoon. "Another Christian right? The politicization of Korean Protestantism in contemporary global society." Social Compass 61, no. 3 (2014).

|

|