확장, 경쟁, 경계 만들기: 조선과 명의 압록강 주변 지역 국경 문제

국문초록

본문은 압록강 하류가 애매한 경계로부터 분쟁이 있는 국경지대로, 그리고 국분적인 선형 경계선으로 변화하는 과정을 연구하였다. 이는 조선과 명나라 요동 간의 동적 변경관계가 작용한 결과이다. 압록강 하류의 완충지대가 생겼을 때 조선은 15세기 말까지 이 지역의 섬들을 유연하게 인식하고 실제 영향력을 미치게 했다. 요동의 인구가 이 지역으로 물리면서 조선과 명나라의 영토 분쟁이 첨예해졌다. 임진 왜란의 영향으로 양국은 이 섬들을 공동 개발하여 17세기 초 이 지역에서 명확한 경계선 의식이 생겼다. 한편으로는 성장된 국가 역량, 자원 개발에 대한 경쟁, 다차원적인 교섭은 공동적으로 조선-요동 국경의 유동성을 형성하였다. 다른 한편으로는 바로 이러한 상호 작용 과정에서 국가간의 경계활동과 영토 인식이 완벽해진 것이다.

주제어: 압록강, 조선, 명나라, 국경관계

Abstract

This study investigates the transformation of the lower Yalu River from an ambiguous to a contested boundary and its partial linearization as the consequences of dynamic border interactions between Chosŏn Korea and Ming Liaodong. The establishment of an uninhabited region between Liaodong and Korea enabled the Chosŏn state to flexibly perceive and exert influence over the vacant Yalu River islands before the late fifteenth century. Its territorial tension with Ming China was then sharpened by the inflow of the Liaodong population into this area. The joint exploration of these islands under the impact of the Imjin War soon impelled the determination of a distinct boundary line in the early seventeenth century. While expansive state powers, their competing resource exploitation, and multilevel negotiations together shaped the fluidity of the Chosŏn-Ming boundary; it was also in this interactive process that their boundary-making activities and territorial conceptions were refined.

KeyWords: Yalu River, Chosŏn Korea, Ming China, border relations

Introduction

Although the Ming and Chosŏn states recognized the Yalu River (K. Amnok River) as the demarcation of their territories, this boundary was far from a static and distinct line free of controversy and rivalry. Throughout the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries, the two governments and their subjects increasingly encountered and interacted on the dotted river islands of the lower reaches of the Yalu River, a region that easily lent itself to mutual exploitation and inhabitance. This led to substantial contestations and negotiations concerning territorial security and border separation between the two states.

Past scholarship has paid attention to the related historical facts, including the advancement of Ming military projects toward eastern Liaodong and the anxiety this issue brought to the Chosŏn authorities, and the fluctuant cultivation of the Yalu River islands and their disputable territorial ownership. These research results understand Ming-Chosŏn relations within an impact-response framework, regarding the latter as being threatened by and then reacting to Ming hegemony. 1 They also argue whether these river islands belonged to Ming China and view the Chosŏn-Ming bilateral negotiations on the prohibition of cultivation of these islands as a concession to each other. This research tendency shows that “strong nationalism in China and Korea makes contestation over the border an ongoing process.” 2 In general, these examinations neglect Chosŏn Korea’s agency in influencing the environmental and political landscapes of the border region, or are prone to narrate the Chosŏn-Ming territorial tension over the Yalu islands from a present-day perspective rather than comprehending this case in its specific temporal and spatial contexts. Instead of understanding the boundaries between Chosŏn Korea and Ming/Qing China as explicit and fixed, some recent studies reveal that the divergencies between the vassal and the suzerain states furthered the uncertain and contested nature of their territorial boundaries. Scholars tend to regard the Yalu River boundary as a flexible region shaped by overlapping spheres of influence. 3 Some highlight Chosŏn Korea’s “proactive counterstrategies” against Ming border policies in this process. 4 In particular, Seonmin Kim’s monograph demonstrates the obscurity of the Qing-Chosŏn boundary that was intentionally preserved by the Qing’s limitations regarding Manchuria and its asymmetric tributary relations with Chosŏn Korea. Kim’s definition of “borderland” as “a zone of demarcation, a site at which the two neighbors encountered one another and clashed but nonetheless recognized their mutual boundary” is especially instrumental in illuminating the essential feature of early modern Korea-China boundaries. 5

These studies stress early modern Korea and China’s collaborative effort and diplomatic tension in the consistent maintenance of their boundary as an empty and vague space. However, this article sheds new light on the delicacy and complexity of the downstream Yalu River shifting from an unclaimed contact zone to a disputed territorial area, and then to a clear-cut demarcation, at least partially, from the fifteenth to the early seventeenth centuries. It contextualizes this case in the Chosŏn-Ming frontier expansion and cross-border mobility, and displays how this tendency intensified and elaborated their boundary-making practices and produced a growing precision in their territorial consciousness. Moreover, while this investigation corresponds to the current scholarship by emphasizing the dynamics in Korea-China territorial relations, it pays closer attention to the subtle and interwoven roles of local and regional agencies in influencing their border development and management.

Fluid Expansion and Growing Tension in a Buffer Zone

The river islands located near the estuary of the Yalu River formed an undefined frontier between Chosŏn Korea and Ming China. This ambiguity was to a large extent the result of their agreement to intentionally retain the mountainous area of eastern Liaodong as an unpopulated buffer zone since the beginning of their diplomatic relations. The aim of this effort was multifaceted. The primary considerations were to consolidate the Ming state’s border control within its effective jurisdiction, and to preclude potential conflicts with Korean residents. 6

The emptiness of the Yalu River islands created an opportunity for the Chosŏn polity to develop influence for economic and security purposes. Although concerned with border people’s escape and being attacked by the semi-nomadic Jurchens, during most of their reigns King Sejong (r. 1418–1450) and King Sejo (r. 1455–1468) allowed at least a conditional exploitation of the three islands—usually Ŏjŏkto Island 於赤島, Wihwado Island 威化島, and Kŏmdongdo Island 黔同島—between the lower branches of the Yalu River. This provided a means of livelihood for Ŭiju peasants, who would otherwise have struggled to make ends meet due to the small size of Ŭiju arable lands. 7 This consideration also strengthened the Chosŏn border defense, a reflection of its expansive policy toward the north regarding the Jurchen threat in the early and midfifteenth century. In terms of expanding royal jurisdiction, Korean kings appeased the Jurchens by offering them military posts and permitting them to conduct trade in Seoul. 8 In addition, the Chosŏn government actively launched military operations, constructed the defensive wall and military garrisons, and relocated people to develop the Tumen and Yalu frontiers when facing Jurchen invasions. As far as the Yalu islands were concerned, King Sejo strongly stated the necessity of their exploration. He advocated this strategy for the manifestation of royal prestige, as well as to resist the Jurchens possibly claiming possession of this region if his subjects stopped farming there. 9

Chosŏn Korea’s administrative and agricultural extension interacted with its vague and fluid perception of the Yalu River islands. For instance, Sejong officials regarded Ŏjŏkto Island as a frontier beyond Ming territorial sovereignty, a notion that facilitated their proposal to authorize its cultivation and taxation. 10 In conformity with his tough attitude toward the Jurchens, in the mid-sixteenth century King Sejo further described the three islands as within Korea’s territory. While some officials suggested abandoning this region to avoid direct contact with Jurchen enemies on the Ŭiju border, he insisted on maintaining the presence of Korean power there, saying, “How could we leave our territory in a hurry just because of a small setback?” 11

In response to its aggravated friction with the Jurchens, Ming China had also begun to reinforce its military strength near the Yalu River boundary beginning in the Tianshun reign (1457–1464). Before that, eastern Liaodong had long been beyond the effective control of the Liaodong Military Commission (C. Liaodong dusi, 遼東都司), the basic unit the Ming state established to govern the Liaodong peninsula, leaving only the Lianshan Pass 連山關 180 li (103.68 km) southeast of Liaoyang City being guarded. 13 As seen in Korean historical accounts, this region was often called the “East Eight Posts” (K. Tongp’alch’am, 東八站) due to its eight abandoned courier stations constructed by the Mongol Yuan. The stations connected the Yalu riverbank and the land east of Liaoyang, and formed the only official route between Korea and China proper during most of the Chosŏn-Ming diplomatic communications. Since the harsh natural environment and rampant Jurchen attacks in the East Eight Posts brought enormous difficulties to Korean missions to China, the Chosŏn court sent requests to the Ming central government in 1436, 1438, 1450, and 1460, asking for a less-dangerous tribute route to be opened. 14

Although the Ming government rejected this proposal, it decided to put more effort into its defense against the Jurchens. After almost a century’s absence of administration in the East Eight Posts, the Ming government began to extend the Great Wall, together with its watch towers, to the Yalu River boundary near Ŭiju beginning in 1459. 15 This attracted the Chosŏn state’s close attention, as seen in its envoys’ and local officials’ persistent observations on the progress of this project. For instance, in 1469 a special commissioner of P’yŏngan Province carefully surveyed and reported on the scale, form, and distance of the Great Wall to Korea’s northwest border. 16 Fortresses, the basic defense element along the Great Wall, had also been effectively established. According to Korean envoys who passed through Liaodong, in the same year five fortresses were newly completed in northeastern Liaodong. 17 During the 1480s and 1490s, the Ming government continued to construct a series of courier stations, Fenghuang City 鳳凰城 and the fortresses of Zhendong 鎮東堡, Zhenyi 鎮夷堡, and Tangzhan 湯站堡, toward the China-Korea boundary. 18

The Ming’s ongoing construction of the East Eight Posts during the late fifteenth century produced great anxiety on the part of the Chosŏn Korean government regarding its northern border security, resulting in frequent court discussions on appropriate countermeasures. Some major considerations included strictly prohibiting Korean people’s border trespassing, 19 lightening the corvée burden of P’yŏngan residents to discourage their desertion, 20 establishing a garrison in the estuary of the Yalu River to separate the intermingling P’yŏngan and Liaodong populations, 21 and consolidating the Ŭiju border defense, such as reconstructing Ŭiju City, building a defensive wall, and enhancing military preparations. 22

The Chosŏn government had also considered cultivation of the three islands to be an effective method to prevent the Ming, instead of Jurchens, from occupying the Yalu River buffer zone. In 1470, the year when King Sŏngjong ascended to the throne, the subject of whether to urge Korean peasants to farm the three islands once again became a heated issue among Chosŏn officials. Although P’yŏngan regional military commissioner Yi Ch’ŏlgyŏn 李鐵堅 informed Sŏngjong of Ŭiju residents’ reluctance to exploit the islands, Chief State Councilor Sin Sukchu(申叔舟) firmly supported the implementation of this strategy, referring to Sejo’s intention to reclaim the islands due to concern over the Chinese people’s seizure of them. To reduce the inconvenience of the Ŭiju indigenous residents traveling back and forth across the river, Sin further suggested their long-term settlement under a more-complete protection strategy. 23 It should be noted that Sin’s citation of Sejo’s words differed from the latter’s above aspiration of cultivating the three islands to handle the Jurchen problem. While this act may have been a use of rhetoric for the purpose of persuading Sŏngjong, it at least shows that Ming China’s growing military influence had become a priority of the Chosŏn court. Sŏngjong indeed accepted Sin’s suggestion, who then proposed detailed measures such as deploying armed forces and constructing defensive infrastructure on the three islands, and disciplining and organizing peasants to go there in the farming season. 24

While Yi Ch’ŏlgyŏn opposed an immediate and compulsive application of this arrangement in order to save local manpower, he agreed to be prepared to establish further control of the Yalu River region: “Although we do not cultivate the three islands now, we have built watchtowers and palings, [which means we] will not abandon the region. If China finishes the construction of the Great Wall and further strengthens the defense [of this region], it would be the same as our interior land. [Thus] waiting for five or six years to enter and cultivate it would not be too late.” 25 Yi Ch’ŏlgyŏn’s and Sin Sukchu’s specific plans differed from each other based on their respective estimations of local conditions, and this divergence between Korean provincial governors and court officials lasted into the following decade. 26 However, their strategies were framed under the common goal of exercising authority over the three islands and taking the precaution of transforming them into Korean territory. At this time, the Chosŏn Korean government was still considering free and flexible use of the Yalu River islands. However, it had to confirm the legitimacy of this after encountering the Ming extending its jurisdiction. In 1488 when Fenghuang City was completed, the commander submitted a proposal to the Liaodong Military Commission, asking that Ŭiju soldiers be prohibited from crossing the Yalu River for poaching and digging, and for stealing from Liaodong inhabitants. This document was then transmitted to King Sŏngjong. It triggered debate among his senior officials on how to define and clarify the territorial sovereignty of the Yalu River region. Sŏngjong first raised doubt about whether the Liaodong Military Commission had the authority to send out this document without the permission of the Ming emperor, indicating his discontent with Liaodong’s direct intervention in this issue. Regarding the ownership of the three islands, the Chosŏn Royal Secretariat stated that the land on one side of Chŏkkang River 狄江, a northwest branch of the Yalu River, belonged to Ming China, whereas the three islands were on the other side and should be considered within Korea’s territory. 27

However, several days later when Sŏngjong once again discussed this issue with the Council of State Affairs, the Six Boards, and the Hansŏng City Administration, they conjectured that these islands were either beyond Ming and Chosŏn jurisdiction or within Ming territory, and the Chŏkkang River was actually inside China instead of forming the boundary line. To prevent latent diplomatic tensions as well as maximize Chosŏn’s interests, they put forward a meticulous and flexible handling of the cultivation issue: although the related preparations could be postponed for further consideration, they should not report this matter to the Liaodong Military Commission, leaving the actual control of this region negotiable and operational. As they explained, the Ming had never before prevented Korean people from cultivating the three islands. However, if the Chosŏn state argued the current dispute with Liaodong, the latter would be required to investigate further and submit the case to the emperor, which could arouse the Ming’s interest in these islands. 28

This discussion reflects that although the Chosŏn court was able to capitalize on the vagueness of the Korea-China frontier, it also had to avoid making this situation known to the Liaodong Military Commission or even to the Ming central government. While most cross-border affairs between Ming China and Chosŏn Korea were solved at the administrative level of the Liaodong Military Commission, if a contentious issue was considered to be serious enough, the Liaodong office would submit it to the Ming central government for further judgment. Due to the decision-making power Liaodong and Beijing held in their interactions with the vassal state, Chosŏn would have been concerned about a loss of advantage if Ming China clarified the territorial uncertainty of the three islands. It can be seen that compared to the Chosŏn central and local governments’ inclusive perceptions and policies toward the three islands since the early fifteenth century, Sŏngjong and his officials had a more-cautious response after the Liaodong Military Commission extended its influence to near the Yalu River, demonstrating the restriction the Chinese-Korean hierarchical tributary relations put on the border policy of the Chosŏn authorities.

The Formation of a Contested Borderland

Although the Chosŏn state began to consider a counterstrategy early, its concern was finally realized when Liaodong migrants began to settle on the Yalu River islands in the early sixteenth century. Their direct contact and conflict with Chosŏn inevitably transformed this buffer zone into a shifting borderland. What made this influx of Liaodong population possible was their escape from military garrisons for reasons such as the turbulence of northeast Chinese society, the collapse of the military farming system, and Ming bureaucratic corruption after the early fifteenth century. 29 The incorporation of eastern Liaodong into the Ming defense system accelerated this process. With the establishment of military fortresses and the Great Wall, as well as the subsequent reconstruction of Yuan courier stations, evaders continuously entered the Liaodong mountainous region. This propelled their illicit movement toward the Yalu riverside and islands, an increasingly visible phenomenon recorded in P’yŏngan official reports. 30

Stimulated by emerging economic changes in Korea and China, it was also during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries that border smuggling began to grow. With the collapse of the rank-land system (K. kwajŏnbŏp, 科田法) that had been applied in Korea since the late Koryŏ and early Chosŏn, land became concentrated in the hands of private landowners. This reform resulted in the transformation of tenant peasants into businessmen and artisans, and promoted the development of the transaction mechanism and the marketization of surplus products in the reign of Sŏngjong (1457–1495). It even fueled a rapid increase in the demand for luxury goods and their consequent import from China in the following Yŏnsan’gun (1476–1506) period. 31 In China the gradual establishment of a silver-based monetary system in the sixteenth century led to a boom in the domestic private economy. In spite of the reinstatement of the sea ban policy in the mid-sixteenth century, the need to import silver and export Chinese commodities significantly activated China’s international trade. 32 Consequently collaborative interactions between Liaodong and P’yŏngan residents in the informal economic activities of smuggling and stealing became more dynamic. 33

Under these circumstances the Chosŏn Korean government was eager to eliminate border crossings for the protection of its state security. After noting the existence of Chinese communities on the Yalu islands it communicated with the Liaodong Military Commission, asking for the cultivation of this region to be prohibited and remaking the Yalu River into a depopulated boundary. While Liaodong officials in general accepted the Chosŏn court’s request, their individual reactions varied, reflecting the nuances and tensions in Liaodong-Chosŏn diplomatic negotiations. Some of these officials displayed a vague territorial consciousness of the Yalu River islands. For instance, in 1528 when Korean envoys informed the Liaodong chief commander of several Liaodong escapees residing by the Yalu River, the latter denied the legitimacy of this situation: “How can the vast territories of the Great Ming be left and ordinary people be permitted to live in a dangerous place in the middle of the river!” 34 On the other hand, some seemed to be more wary of the boundary issue. Liaodong Regional Investigating Censor Yang Xingzhong(楊行中) once questioned the Liaodong commissioner and commander’s decision to repatriate the Liaodongnese from Wihwado and Wŏnjikto(圓直島) islands, 35 since they were “residents on the boundary”(疆界居民). 36 Several years later, the newly appointed Liaodong censor, Hu Wenju(胡文舉), expressed this perspective more explicitly. He believed that it was legal for Chinese people to inhabit and cultivate the area in the middle of the river, “the Chinese boundary”(中國界限), and therefore did not understand the Chosŏn government’s concern. 37 There were also influential Liaodong military officers, such as a fortress guardian, Han Chengqing(韓承慶), who diametrically opposed the prohibition policy the Chosŏn suggested. According to Chosŏn senior officials, Han’s reaction was due to his deep-rooted power in the locale and close personal relationship with the Liaodong escapees to the Yalu islands. 38

More apparent and lasting contestations appeared between Liaodong violators and the two governments. This is first reflected in Liaodong evaders’ recurring occupation of the Yalu islands. From 1532 to 1541 alone Liaodong and Chosŏn officials cooperated to expel these people six times, but after one year or less they returned and resumed their farming. In the prohibition process they even defrauded, accused, or fought Chosŏn officials. 39 The claims of the Chosŏn court and Liaodong individual cultivators regarding the utilization and disposition of these river islands were also contradictory. In 1533, after learning of the Ŭiju forces’ conflict with the Liaodongnese on Kŏmdongdo Island, King Chungjong raised concern about whether the Chinese government had recognized and authorized these people’s inhabitance. If so, the Ŭiju military crossing the Yalu River to expel the Chinese on an island that did not belong to Korea would develop into a more-serious dispute with the Ming state. 40 Several days after the three state councilors of Chosŏn replied that while they would certainly not contend for land with the “Superior Country,” Korean people had previously cultivated Kŏmdongdo Island while Chinese people had never occupied this land. The making of this coherent declaration, as also shown in Sŏngjong and his officials’ above discussions, was for the purpose of building a historical and practical foundation for the Chosŏn court’s resistance to the current existence of Liaodong people on the Yalu River islands. The councilors also argued the validity of the Ŭiju military operation, stressing that both the Liaodong commissioner and the Shandong censor had already agreed to repatriate their subjects and empowered the Chosŏn government to deal with this matter. 41 In conclusion, although Ŭiju soldiers could not engage the Chinese with force, the Yalu River farmlands could at least be trampled to enforce the prohibition order. 42

The Chosŏn state further legitimized its former exploration of the three islands by asserting their sovereignty in both domestic and external contexts. As seen in the comprehensive geographical treatise Shinjŭng tongguk yŏji sŭngnam 新增東國與地勝覽 that was completed in 1530, the three islands were recorded under the category of the Ŭiju landscape. 43 This understanding was also applied to Chosŏn’s practice when facing doubt from Liaodong. For instance, in 1541 some Liaodong military officers saw the ridges remaining on Ŏjŏkto Island and questioned whether Korean people still farmed this area in spite of the restriction. A Korean interpreter who was sent to communicate with Liaodong argued that while Korean peasants did indeed obey the current regulation, they had once cultivated this island because it was “originally inside our country’s boundary” 本是我國界限之內. 44

In contrast, the Liaodongnese attempted to eliminate the influence of this prohibition. In 1534 the repeated failures to repatriate the Liaodongnese forced the Chosŏn and Liaodong governments to erect three steles on Kŏmdongdo Island, Wihwado Island, and Sŏrhamp’yŏng Ground 設陷坪, inscribed with the order, “Liaodong military and commoners are prevented from living and farming here and Korean military and commoners are prevented from crossing this [area] for poaching and digging.” 45 However, these symbols that represented the formal agreement on recreating a narrow zonal boundary were soon demolished or damaged by illegal Liaodong cultivators. They even altered the inscription to state that they were originally permitted to live and farm there, and supported this misleading claim by secretly possessing and trading for the forbidden land in silver. 46

As a result, the Liaodong government had to routinize the prohibition in 1541 by reestablishing the steles, patrolling the islands, and reporting violation cases every month. 47 However, this policy only remained effective for a very short period. Although the Chinese seemed to disappear completely from the Yalu River boundary the following year, 48 Korean officials soon complained that they returned and defied the government order with a “stubborn and violent” heart. 49 This tension with outlaws continued throughout the second half of the sixteenth century. Therefore, the Chosŏn and Liaodong governments had to repeatedly communicate with each other on reinforcing the prohibition. 50

This bilateral negotiation was made more complex by interactions and disputes among local individuals and officials, as reflected in the varying situations of the prohibition steles in the following years. In 1562 the administrator of a Liaodong border fortress discussed allowing his subjects to cultivate land south of Sŏrhamp’yŏng Ground with the Ŭiju government. This was probably to produce sufficient provisions in order to strengthen the military power of this fortress. The Liaodong Military Commission and the Chosŏn court accepted this request and agreed to add a prohibition stele to the lower part of this area, leaving its main body available for cultivation. 51 Another case occurred during the 1580s when Liaodong residents recurrently appeared on Chosanp’yŏng Ground 造山坪. Although the Chosŏn court asked the Liaodong Military Commission to build another prohibition stele there in 1583, two years later the Liaodongnese complained about this decision to their censor-in-chief and requested that the location of this stele be changed in order to widen the arable land of Chosanp’yŏng Ground. 52

Creating a Linear Boundary Line: Roles of Zhenjiang, Chosŏn, and Liaodong

While multiple tensions formed a controversial space on the Yalu River, before the two Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598) the Liaodong and Chosŏn governments did reach a consensus on keeping this zone depopulated, a conventional practice to prevent border trespassing and secure respective jurisdictions. However, in the 1590s the Ming and Chosŏn rulers boosted their transnational mobilization of military forces and provisions, and licensed private transportation and trade across the border region to defend against the Japanese attacks. 53 This economic and military cooperation that was officially recognized and encouraged unprece-dentedly interconnected the territories along the Yalu River during and right after the Imjin War. A noteworthy example of this situation is the opening of the periodic Chunggang market in 1594, which was located on Chosanp’yŏng Ground near the Chunggang River 中江. As part of the newly emerging trade on the Korean-Chinese borderland to support the war, this market offered military provisions such as grain, horses, and donkeys from China in exchange for ginseng, marten fur, and fabrics in Korea. It also played a necessary role in supporting Korean society by advancing the plentiful and frequent inflow of Liaodong grain. After the war the market continued to provide essential supplies to Korea by exporting ginseng and luxury items to China. The Ming and Chosŏn governments even jointly appointed officers to supervise and collect taxes from Chunggang merchants, making the market an important channel for increasing fiscal revenues until its suspension in 1613. 54

In addition to the regularization of commercial exchange on the border, the Yalu River islands were included in military farming as a wartime strategy for increasing provisions. In 1594, during the stalemate of the Imjin War, the Ming Ministry of Revenue required the Chinese defensive forces along the river to cultivate the wastelands of this region. 55 Although the Chosŏn court objected, this plan was implemented by the Liaodong Military Commission in spring 1595. 56 As one Korean envoy observed in 1599 right after the war ended, Wihwado Island, which was previously within the scope of the prohibition policy, had already been fully exploited. Chinese people had even established a village there. 57

Illicit trading and trespassing on the Korean-Chinese border was also rampant. According to a P’yŏngan provincial governor, the smuggling of gunpowder in particular flourished between the Ming border population and Korean merchants. A more serious issue was that Ŭiju smugglers crossed the Yalu River in groups and stole gunpowder from Liaodong. 58 Even state agents, such as Korean and Liaodong military officers, failed to control the overactive border market and were deeply involved in illegal economic activities such as imposing additional taxes and extorting money from Chunggang merchants. 59

The thriving transborder interactions and the consequent administrative challenges impelled the Chosŏn court to reiterate the necessity of keeping its boundary delimited from the Ming’s as soon as the Japanese threat was removed. 60 More importantly, drawing a clear line between their territories would relieve the political tension triggered by borderland issues, as reflected in Ming counselor Ding Yingtai’s(丁應泰) far-fetched accusation in 1598. In this memorial Ding claimed that the Korean people colluded with the Japanese to invade China, due to the former’s intention to recover the eastern Liaodong, a region that originally belonged to the Koryŏ kingdom. Ding even viewed the catalyst of this event as the Chosŏn-Liaodong dispute over the Yalu islands. 61 This malicious charge provoked a serious diplomatic crisis for the Chosŏn court, forcing it to repeatedly defend itself to the Ming government and deny the rumor of its recovery of former Koryŏ territory. It stressed the concerted prohibition with the Liaodong Military Commission instead of their conflict over the exploration of the Yalu islands. 62 Although the Chosŏn court successfully convinced the Ming emperor and resolved this problem, the potential risk was not eliminated. In fact, Ding Yingtai’s words were not completely groundless in light of the farming clashes referred to earlier. As a result, it was imperative for the Chosŏn to settle this politically sensitive issue by creating a linear boundary with Liaodong in the most disputed area of the downstream Yalu River. To determine the territorial ownership of Nanjado Island(蘭子島) and Ch’ejado Island(替子島) (namely Kŏmdongdo Island), the two joined islands between the east and west branches of the Yalu River, were at the core of this discussion. Fortunately the Sadae mun’gwe(事大文軌), the collective diplomatic correspondence mainly between Chosŏn Korea and Ming China in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, preserves copies of the original documents on this event and greatly helps our understanding of its process and consequences under the combined actions of various participants.

In 1595 when the Ming military reclaimed Wihwado Island, the Koreans were permitted to exploit Nanjado Island and Ch’ejado Island. However, only four years later Liaodong migrants Sun Dechun(孫得春) and his companions, who were under the jurisdiction of Zhenjiang City(鎮江城), 64 planned to farm on Nanjado and Ch’ejado islands and triggered a dispute with the Korean cultivators there. This lawsuit induced the Zhenjiang Office to reinstate the prohibition policy on these two islands. 65 The Chosŏn court raised an objection to this arrangement in front of a provincial assistant administration commissioner, Zhang Dengyun(張登雲), who was in charge of the Liaohai Dongning Circuit(遼海東寧道). As a result, the Koreans successfully obtained the right to farm the two islands as before. Sun and the others were amerced. 66

However, this privilege did not last long. In early 1600 the Zhenjiang Office, which directly participated in handling Liaodong border affairs, had already attempted to have the two islands lie idle as a ranch for its own use. It blamed the Korean people for disobeying this rule and ordered a strict survey of this land and an erection of a stele to prevent possible infractions. Ŭiju soldiers and commoners opposed this policy and requested its cancellation in order to maintain their living. The Chosŏn court then transmitted this case to Zhang Dengyun and the Liaodong Military Commission, continuing to ask for the Korean farmlands on Nanjado and Ch’ejado islands to be retained. 67 This time Zhang denied this appeal. As he explained, an important reason for his agreement with the Zhenjiang Office’s decision was to compensate for the suzerain state’s huge consumption of resources when aiding Korea against the Japanese attacks. 68

The Liaodong Military Commission further ascribed the dispute on Nanjado and Ch’ejado islands to their territorial ambiguity. It stated that if the Yalu River was viewed as the demarcation line between China and Korea, the two islands were on its western side and therefore belonged to China. If the two states were divided by the Chunggang River as the Chosŏn claimed, then the two islands were to the eastern side of the river and should be within Korea’s territory. Here the “Yalu River” specifically represented its eastern tributary that was closer to the Korean Peninsula, a declaration more favorable to Liaodong’s territorial interests. In contrast, the Chosŏn state claimed the real boundary to be the Chunggang River, which was the upstream portion of the west branch of the Yalu River and could also refer to the whole branch. To compromise between the two divergent views, the Liaodong Military Commission ruled to keep the Korean farmlands that were reclaimed before 1595 intact. 69

The vague use of the term “Yalu River” intensified this contradiction. In 1601, after noting the emergence of Korean cultivators on Nanjado Island, the Zhenjiang Office reinforced the prohibition policy. 70 The Chosŏn court once again dissented. Its concern, as described by a senior official, was that although the Zhenjiang ranch was unpopulated at present it had already been incorporated into Chinese territory and could be further developed under the Ming’s actual control. 71 On the other hand, the Zhenjiang Office claimed that Chosŏn Korea had fabricated the report on the location of Nanjado Island as being on the eastern side of the Yalu River rather than toward its western bank. 72 The primary cause of this dispute was the obscure reference of the “Yalu River.” While the Zhenjiang Office’s opinion was in line with the Liaodong Military Commission’s above statement, the Chosŏn court used this name to denote the Chunggang River, or more generally the western branch of the Yalu River. The need to avoid this confusion prompted a reinvestigation of the boundary line. 73 In its diplomatic correspondence with Zhang Dengyun and Liaodong vice commander Wang Weizhen(王維貞), who took charge of Zhenjiang affairs, the Chosŏn court explicated its border consciousness and boundary identification at length. It first stated the basis of its designation of the Yalu River, explaining that although the tributaries around the Ŭiju region, including the Chunggang River, had their respective names, they were generally called the “Yalu River” due to their common source. It then argued that Nanjado and Ch’ejado islands were originally set as the delimitation. To support this notion, the court prioritized its negotiations with Liaodong on creating a forbidden zone around this river from Sŏrhamp’yŏng Ground to Wihwado Island during the mid to late sixteenth century, indicating the validity of the Chunggang River in defining a zonal boundary. Regarding its current concern, the Chosŏn court skillfully transformed this contested borderland into an explicit line and accordingly expanded its territorial conception, stating that Nanjado and Ch’ejado islands to the eastern side of the Chunggang River, the well-defined boundary, were “apparently Korean fields”(顯係朝鮮田土). In addition to this manipulation of words, the Ming government’s consent to Korean people’s cultivation of the two islands during the Imjin War provided a legitimate basis for the Chosŏn state’s practical control over this region. At the end of the document the court concluded that the Zhenjiang Office used the general term “Yalu River” to exclusively designate its east branch and ignored the fact that the Chunggang River was the actual state boundary. 74

The reappearance of Sun Dechun and his companions on Nanjado and Ch’ejado islands in 1604 further promoted the ultimate determination of the islands’ territorial ownership. This time Liaodong senior officials penalized Sun more heavily by flogging him ninety times and banishing him for two and a half years. They also formulated a verdict to accept and authorize the Chosŏn court’s territorial declaration. 75 On Ch’ejado Island a ditch was then excavated to function as a linear boundary between the two states, and a tablet was established inscribed with a statement declaring that Chosŏn Korea was judged to be in possession of Nanjado and Ch’ejado islands. 76

Local contestations over resources and jurisdictional controls led to intricate territorial negotiations between the Zhenjiang Office and the Chosŏn court. For the Zhenjiang Office, the enclosure of the Yalu islands could allow it to preempt their natural resources and facilitate their fuller exploration. Therefore, Zhenjiang repeatedly impeded the Chosŏn’s intention to reclaim an empty region and tended to reasonably manage it by claiming the east tributary of the Yalu River as the common boundary. For the Chosŏn king and officials, the establishment of their territorial sovereignty over Nanjado and Ch’ejado islands would not only ease border residents’ struggle to survive, but also further resistance to the growing Chinese sphere of influence that could otherwise directly border on and threaten Ŭiju, the military stronghold of northwestern Korea. In order to protect its economic benefits and border security the Chosŏn court invoked the Liaodong government’s support, rhetorically linearized the zonal boundary of the Yalu River, and, most importantly, competed with Zhenjiang in defining the location of the boundary line.

Having to consider and balance the claims of both Zhenjiang and Chosŏn, Liaodong administrators’ stances were more nuanced and vacillating. When Zhang Dengyun first heard Chinese migrant Sun Dechun’s case, he accepted the Chosŏn’s petition of opening up Nanjado and Ch’ejado islands. However, after he was informed of Zhenjiang’s policy of emptying land and its censure on Korean cultivators’ violations, he moved to Zhenjiang’s side. Moreover, when the Liaodong Military Commission was uncertain about the veracity of Zhenjiang’s and Chosŏn’s claims regarding the Yalu River boundary, it adopted a neutral perspective and satisfied both to a certain extent. But Liaodong senior officials eventually tipped the balance toward Chosŏn Korea. Differing from the combativeness of Zhenjiang officers and residents, Liaodong officials’ final decision aimed to reconcile the territorial contradictions sharpened by Chinese migrant Sun Dechun’s trespassing. This was not only for manifesting their lenience toward the vassal state of Korea but for preventing this case from being disclosed to the Ming court and themselves from being blamed due to their negligence in regulating the border. This attitude comported with Liaodong officials’ common practice when handling cultivation disputes: although their individual responses would vary, they usually took the Chosŏn’s requests into account and agreed to keep Chinese and Korean territories separate to maintain order in their border interactions and tributary relations.

As for the Korean side, it was also essential to maintain a neighborly relationship with Liaodong. Due to the geographical contiguity of the Korean and Liaodong peninsulas, active and diverse exchanges occurred more often in their border region than in any other place. This situation required the Liaodong Military Commission’s and sometimes Liaodong civil officials’ direct and frequent involvement in solving border matters. Moreover, the Liaodong Military Commission played an intermediary role in connecting Beijing and Seoul, such as conveying information between the two central governments, directing and licensing Chosŏn envoy trips. 77 This interrelation with Liaodong compelled the Chosŏn government to treat trespassing cases cautiously without easily informing the Ming central government. Moreover, Chosŏn Korea itself was reluctant to escalate border disputes that could cause the Ming court to doubt the vassal state’s loyalty, as occurred in Ding Yingdai’s mistaken accusation. Based on these considerations, the Chosŏn court adopted a similar standpoint to Liaodong senior officials, keeping the resolution of most trans-boundary cases a regional-level practice. As the immediate result of multilayered negotiations in the circumstances of border contact and resource shortages, the existence of the linear boundary in the downstream portion of Yalu River did not last long. After the Manchus annexed Liaodong and invaded Chosŏn Korea in the 1620s, they established a covenant with the latter that emphasized the Yalu River as the boundary and required the two states to guard their territories respectively. 78 However, Korean border trespassing and poaching driven by the high value of ginseng provoked the Manchus. 79 After the Manchus reattacked Korea in 1637, to rehabilitate the economy of its northwestern provinces the Chosŏn government directly encouraged the ginseng trade, leading to more border crossings and the Manchu Qing’s furious opposition. 80 The Yalu River boundary was therefore made an arena of competition, and the delimitation event in the early seventeenth century remained a historical memory. 81

Concluding Remarks

After the Qing regime conquered China proper in the mid-seventeenth century, Manchuria was reserved as its birthplace and the Willow Palisade was constructed to fence the Yalu River region. In the meantime, successive warfare impoverished the Korean border region and forced its residents to abandon the Yalu River islands. Only after the political situation stabilized in the eighteenth century, the Chosŏn government began to consider reclaiming and defending this land. 82 While scholars like David Bello and Seonmin Kim stress the Qing’s isolation of its northeast region to preserve unique natural resources and distinguish the Manchu identity, 83 this policy also inherited the tradition of making eastern Liaodong an unoccupied space between the Chosŏn and Ming polities. Therefore, the long-standing practice of insulating this region should be regarded as an important factor not only in Qing imperial formation, but also in sustaining stable and tranquil relations between early modern Korea and China that reflected the continuity and compatibility of their border policies. However, beginning in the late fifteenth century the size of this space continuously decreased due to the massive movement of population and materials, growing contact on the frontier, intensified exploitation of resources, and transnational warfare. This phenomenon demonstrates John Richards’ analysis that, encouraged by active international trade and expansive state power, unprecedented use of land occurred in almost every region of the world. 84 While Richards’ attention focuses more on the impact of Western colonizers in the newly settled areas, this research shows that Northeast Asian states were also important agencies that placed dramatic intraregional dynamics in the worldwide frontier expansion. Although often limited by the tributary relationship, Chosŏn Korea inclined to employ the uninhabited Yalu River islands. The Ming’s growth of power in the border region was more evident: by constructing infrastructures and stationing troops, it incorporated eastern Liaodong into military and jurisdictional control and penetrated its influence into the Yalu River boundary. Moreover, influenced by the wave of accelerated circulation and commercialization of goods in the early modern world, the border residents of the two states connected and interacted more closely and promoted utilization of resources on the Yalu islands. Richards further states, “Certainly, early modern states tried at times to restrain expansion so that they could control resource exploitation and its profits, and often they encountered difficulties in so doing.” 85 Our research proves that even though the two states attempted to prevent the increasing border contact by keeping the Yalu River region depopulated, they failed to do so. After the Imjin War broke out the large-scale consumption and mobilization of resources led to a thorough and competitive cultivation of the Yalu River islands, resulting in another round of territorial disputes in the first few years of the seventeenth century. Consequently, the exhaustion of natural resources and the directly contiguous state borders stimulated the demand to define a linear boundary and a clear territorial consciousness of this area for the first time. Although this sense of territorial precision that emerged from the delimitation in the downstream Yalu River did not prevail after the international political situation of Northeast Asia changed, the interplay of human and natural resources continued to have a profound influence on the Chosŏn and Qing authorities’ boundary making process in 1885 and 1887. This occurred when both of their subjects increasingly immigrated to the restricted borderland of the Yalu and Tumen rivers for seeking new farmlands. Their conflicting territorial claims caused the two states to carefully investigate the Tumen riverhead. Of course, this event differs very much from the bilateral dispute on the Yalu River islands because of the transitioning international circumstances, environmental conditions, and tributary relations of the two states in the late nineteenth century, a period when their territorial negotiations had been largely influenced by “the modern notion of national space as the core of a state’s sovereignty.” 86 However, cross-border migration and competition for land exploration indeed had an enduring impact on refining Chosŏn Korea and Ming/Qing China’s territorial thinking despite their concrete historical circumstances. Finally, attention needs to be paid to the complex roles of local and regional players in border contact and territorial negotiations. While cultivators’ competitive exploration of the Yalu River islands was often the impetus to the enhancement of state defense and border separation, the private benefit of cultivating the islands sometimes accorded with official stances and escalated the contradictions in the Chosŏn and Liaodong’s territorial dispute. Indigenous residents could even wield influence over border officers’ decisions, such as the Liaodong people’s modification and destruction of a prohibition stele and their successful request to change its location, and the petition of the Ŭiju army and civilians to cancel the prohibition rule. These cases directly address the interactive relations between the official and the private in the locale, where Liaodong fortresses enjoyed a degree of autonomy in managing the borders and put a certain pressure on territorial negotiations. However, as the intercessors, Liaodong senior officials aimed to quell dissent and tension in the masses. Due to the indispensable and decisive role of Liaodong military and administrative institutions in the Ming’s border governance, territorial negotiations and the settlement of sensitive transboundary affairs with Chosŏn Korea were regularized on the Liaodong regional level.

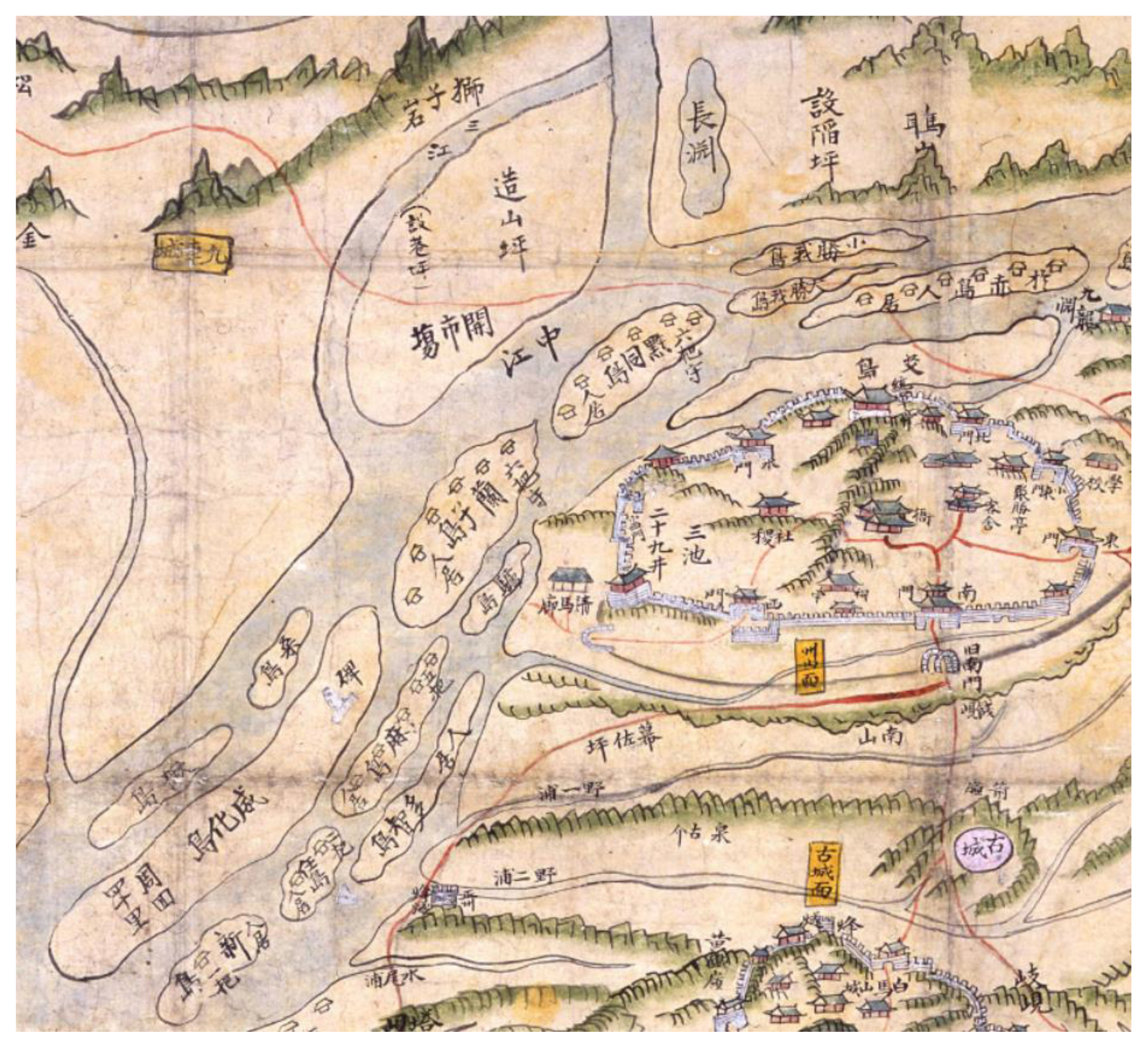

Fig. 1

Yalu River Islands and Ŭiju City, from Yongman chido, collected in the National Library of Korea, 2702–81. 12

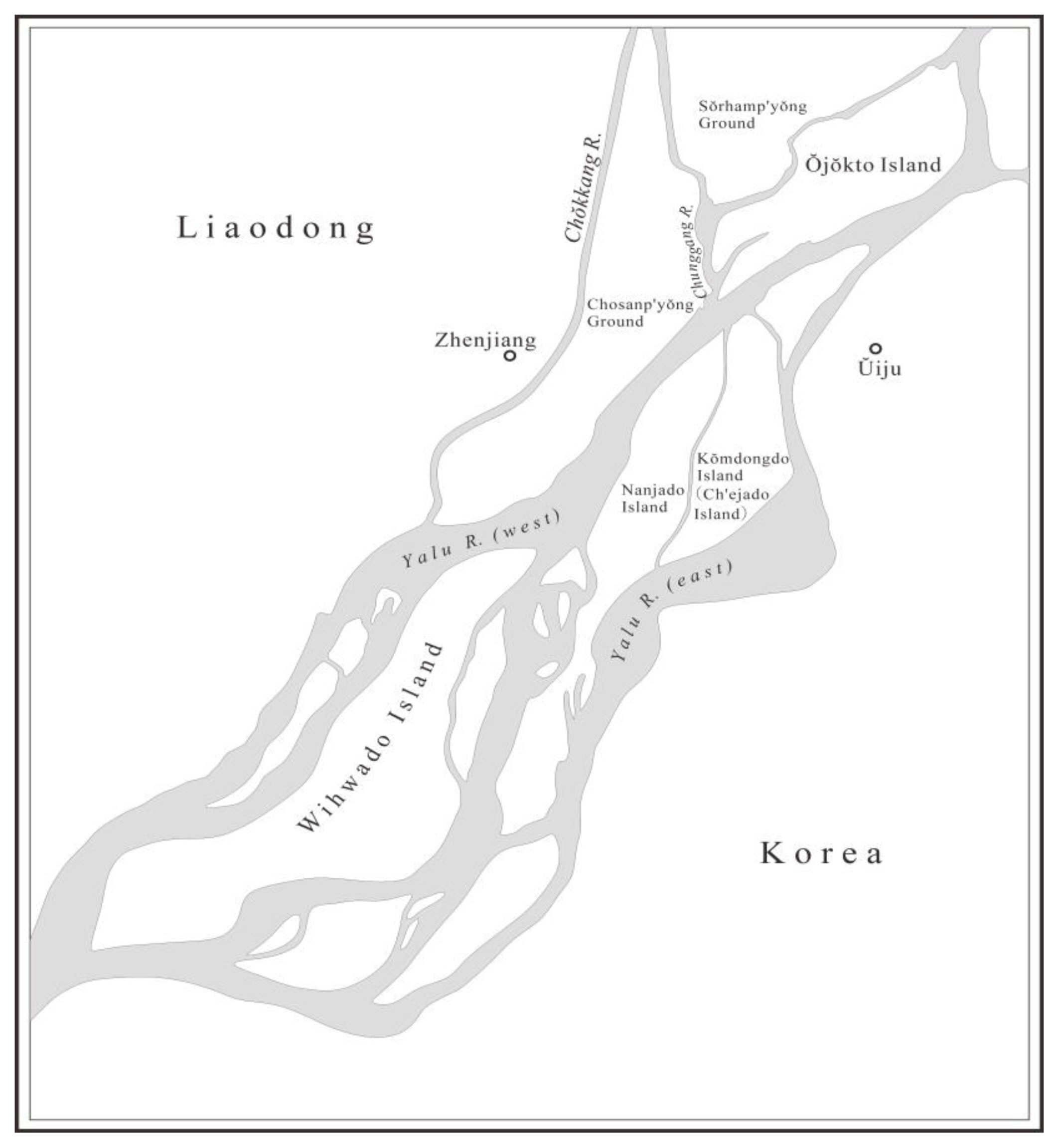

Map 1

The Lower Reaches of the Yalu River (near Ŭiju) 63

References

1. Atwell William. "Ming China and the Emerging World Economy, c.1470–1650." The Cambridge History of China. Twitchett Denis and Mote Frederick W eds. pp 377–416. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998, 8(part 2):  2. Bello David. "The Cultured Nature of Imperial Foraging in Manchuria." Late Imperial China 31, no. 2 December;(2010): 1–33.  3. Cho Ik 趙翊. "Hwanghwa ilgi 皇華日記 [Diaries of Brilliant Flowers]." Yŏnhaengnok chŏnjip 燕行錄全集. [Complete Travelogues of Korean Embassies to China]. 9:Kijung Im eds. Seoul: Tongguk Taehakkyo Ch’ulp’anbu, 2001.

4. "Chungjong sillok 中宗實錄 [Annals of Chungjong]." Chosŏn wangjo sillok 朝鮮王朝實錄. [Annals of the Chosŏn Dynasty]. 14–19. Seoul: Kuksa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏnhoe, 1956.

5. Cong Peiyuan eds. Zhongguo Dongbei shi xiuding ban 中國東北史(修訂版). [History of Northeast China (the Revised Edition)]. Changchun: Jilin wenshi chuban she, 2006.

6. Fang Kongzhao 方孔炤. "Quanbian lüeji 全邊略記 [Record of Border Strategy]." Xuxiu siku quanshu 續修四庫全書. [Supplement to the Complete Books of the Four Treasuries]. 738. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2002.

7. Hasegawa Masato. "War, Supply Line, and Society in the Sino-Korean Borderland of the Late Sixteenth Century." Late Imperial China 31, no. 1 June;(2016): 109–52.  8. Hasumi Moriyoshi 荷見守義. Mindai Ryōtō to Chōsen 明代遼東と朝鮮. [The Relationship between Liaodong and the Chosŏn in the Ming Period]. Tokyo: Kyūko Shoin, Heisei nijūroku, 2014.

9. Ikeuchi Hiroshi 池內宏. "Kōrai Shin-u chō ni okeru Tetsurei mondai” 高麗辛禑朝に於ける鐵嶺問題." [The Issue of Tieling during the Shin-u Period of the Koryŏ Dynasty]. Tōyō gakuhō 東洋學報 8, no. 1 (1918): 82–115.

10. Ikeuchi Hiroshi 池內宏. "Kōrai Kyōbin’ōchō no Tōneifu seibatsu ni tsuite no kō” 高麗恭愍王朝の東寧府征伐に就いての考 [Examination of the Expedition to Tongnyŏng Prefecture during the Kongmin Period of the Koryŏ Dynasty]." Tōyō gakuhō 8, no. 2 (1918): 206–248.

11. "Imun tŭngnok 吏文謄錄 [Copied Records of Documentary Writings]." Changsŏgak K2–3497

12. "Injo sillok 仁祖實錄 [Annals of Injo]." Chosŏn wangjo sillok 33–35.

13. Kim Seonmin. "Ginseng and Border Trespassing between Qing China and Chosŏn Korea." Late Imperial China 28, no. 1 June;(2007): 33–61.  14. Kim Seonmin. Ginseng and Borderland: Territorial Boundaries and Political Relations between Qing China and Chosŏn Korea, 1636–1912. California: University of California Press, 2017.

15. Ku Toyŏng 구도영. "16 segi Chosŏnŭi Amnokkang hagu tosŏe taehan yŏngt’oinshikkwa oegyojŏllyak” 16세기 조선의 압록강 하구 도서(島嶼)에 대한 영토인식과 외교전략 [The Chosŏn’s Perception of the Islands at the Mouth of the Amnok River and the Related Diplomatic Strategies in the Sixteenth Century]. ]." Yŏksa wa hyŏnshil 역사와 현실 97 September;(2015): 233–64.

16. Ku Toyŏng 구도영. "16 segi Chosŏn tae Myŏng pulbŏmmuyŏgŭi hwaktaewa kŭ ŭiŭi” 16세기 조선 對明 불법무역의 확대와 그 의의 [The Expansion of the Chosŏn’s Illegal Trade with the Ming and Its Importance in the Sixteenth Century]." Han’guksayŏn’gu 한국사연구 170 September;(2015): 177–223.

17. Kwŏn Kŭn 權近. "Pongsarok 奉使錄 [Records of a Diplomatic Mission under Orders]." Yŏnhaengnok chŏnjip 1.

18. Li Huazi 李花子. Qingchao yu Chaoxian guanxianshi yanjiu yi yuejing jiaoshe wei zhongxin 清朝與朝鮮關係史研究——以越境交涉為中心. [Research on the History of Qing-Chosŏn Relations: On Their Cross-Border Negotiations]. Yanji: Yanbian daxue chubanshe, 2006.

19. Li Huazi 李花子. Qingdai Zhong Chao bianjie shi tanyan jiehe shidi tacha de yanjiu 清代中朝邊界史探研——結合實地踏查的研究. [Investigation of the History of Qing-Chosŏn Territorial Boundaries: A Study Combined with Field Surveys]. Guangzhou: Zhongshan daxue chubanshe, 2019.

20. "Liaodong zhi 遼東志 [Gazetteer of Liaodong]." Liaohai congshu 遼海叢書. [Collected Works on Northeast China]. Yufu Jin eds. 1:Reprint. Shenyang: Liaoshen shushe, 1985.

21. Min Tŏkki 민덕기. "Chosŏnŭi tae Myŏng kwan’gyewa Ŭiju saramdŭl Amnokgang haryuŭi samdo kyŏngjangmunjerŭl chungshimŭro.” 조선의 對明관계와 義州사람들-압록강 하류의 三島 경작문제를 중심으로 [The Chosŏn’s Relations with the Ming Dynasty and the People of Ŭiju—On the Cultivation Issue of the Three Islands Downstream of the Amnok River]." Hanilgwan’gyesa yŏn’gu 한일관계사연구 49 December;(2014): 43–81.

22. Ming Shenzong shilu 明神宗實錄. [Veritable Records of Emperor Shenzong of the Ming]. Taipei: Zhongyang yanjiuyuan lishi yuyan yanjiusuo, 1966.

23. Ming Shizong shilu 明世宗實錄. [Veritable Records of Emperor Shizong of the Ming]. Taipei: Zhongyang yanjiuyuan lishi yuyan yanjiusuo, 1966.

24. Ming Xiaozong shilu 明孝宗實錄. [Veritable Records of Emperor Xiaozong of the Ming]. Taipei: Zhongyang yanjiuyuan lishi yuyan yanjiusuo, 1964.

25. Ming Xuanzong shilu 明宣宗實錄. [Veritable Records of Emperor Xuanzong of the Ming]. Taipei: Zhongyang yanjiuyuan lishi yuyan yanjiusuo, 1962.

26. Nam Ŭihyŏn 南義鉉. "Myŏng chŏn’gi Yodongdosawa Yodongbalch’am chŏmgŏ” 明 前期 遼東都司와 遼東八站占據 [Liaodong Military Commission and the Occupation of the Liaodong “Eight Posts”]. ]." Myŏngch’ŏngsa yŏn’gu 명청사 연구 21 April;(2004): 1–41.

27. Nam Ŭihyŏn 南義鉉. "Research on Liaodongbazhan and Liaodong Defense Barricade." Journal of Northeast Asian History 6, no. 2 December;(2009): 141–63.

28. Ŏ Sukkwŏn 魚叔權. "Kosa ch’waryo 攷事撮要 [Concise Reference of Historical Facts]." Changsŏgak C15 2A

29. Qiu Guangming 丘光明, Long Qiu 邱隆, Ping Yang 楊平. Zhongguo kexue jishu shi du liang heng juan 中國科學技術史(度量衡卷). [The History of Science and Technology in China]]. Volume of weights and measures. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe, 2001.

30. "Quan Liao zhi 全遼志 [Comprehensive Gazetteer of Liaodong]." Liaohai congshu. 1. Shenyang: Liaohai shushe, 1985.

31. Richards John. The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

32. Robinson Kenneth R. "Residence and Foreign Relations in the Peninsular Northeast during the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries." The Northern Region of Korea: History, Identity, and Culture. Kim Sun Joo eds. pp 18–36. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2010.

33. Ryu Sŏngryong 柳成龍. "Sŏae chip 西厓集 [Collected Works of Sŏae]." Han’guk munjim ch’onggan 韓國文集叢刊. [Collected Works of Korea]. 52. Seoul: Minjok munhwa ch’ujinhoe, 1988.

34. "Sadae mun’gwe 事大文軌 [Documents of Serving the Great]. In ]." Chosŏn saryoch’onggan 朝鮮史料叢刊. [Collection of Korean Historical Materials]." 7. Seoul: Chosŏnsa p’yŏnsuhoe, 1935.

35. "Sejo sillok 世祖實錄 [Annals of Sejo]." Chosŏn wangjo sillok 朝鮮王朝實錄. [Annals of the Chosŏn Dynasty]]. 7–8. Seoul: Kuksa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏnhoe, 1956.

36. "Sejong sillok 世宗實錄 [Annals of Sejong]." Chosŏn wangjo sillok 2–5.

37. Shinjŭng tongguk yŏji sŭngnam 新增東國輿地勝覽. [Newly Augmented Geographical Conspectus of the Eastern Kingdom]]. Seoul: Kyŏngmunsa, 1981.

38. Sŏ Inbŏm 徐仁範. "Amnokganghagu yŏnan tosŏrŭl tollŏssan Cho Myŏng yŏngt’obunjaeng” 압록강하구 沿岸島嶼를 둘러싼 朝·明 영토분쟁 [The Chosŏn-Ming Territorial Dispute on the Islands at the Estuary of the Amnok River]. ]." Myŏngch’ŏngsa yŏn’gu 明清史研究 26 October;(2006): 31–68.

39. "Sŏngjong sillok 成宗實錄 [Annals of Sŏngjong]." Chosŏn wangjo sillok 8–12.

40. "Sŏnjo sillok 宣祖實錄 [Annals of Sŏnjo]." Chosŏn wangjo sillok 21–25.

41. "Sukchong sillok 肅宗實錄 [Annals of Sukchong]." Chosŏn wangjo sillok 38–41.

42. "Sunjo sillok 純祖實錄 [Annals of Sunjo]." Chosŏn wangjo sillok 47–48.

43. Sŭngjŏngwŏn ilgi 承政院日記. [Diaries of the Royal Secretariat]. Seoul: Kuksa P’yŏnch’an Wiwŏnhoe, 1968.

44. Tsuji Yamato 辻大和. "Jūshichi seiki shuttō Chōsen no tai Min bōeki shoki chūkō kaishi no sonpai o chūshin ni” 十七世紀出頭朝鮮の對明貿易-初期中江開市の存廢を中心に [The Chosŏn’s Trade with the Ming in the Early Seventeenth Century—On the Existence and Abolishment of the Early-stage Chunggang Market]. ]." Tōyō gakuhō 96, no. 1 (2014): 1–30.

45. Wan Ming 萬明. Wan Ming shehui bianqian: wenti yu yanjiu 晚明社會變遷:問題与研究. [Brief Discussion on Early Ming Overseas Policy]. Beijing: Shangwu yinshuguan, 2005.

46. Wang Yuquan 王毓銓. Mingdai de juntun 明代的軍屯. [Military Farming during the Ming Dynasty]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1965.

47. Yang Yang 楊旸. Mingdai Dongbei shigang 明代東北史綱. [Liaodong Military Commission during the Ming]. Taipei: Xuesheng shuju, 1993.

48. Yang Zhaoquan 楊昭全, Yumei Sun 孫玉梅. Zhong Chao bianjie shi 中朝邊界史. [History of China-Korea Boundary]. Changchun: Jilin wenshi chubanshe, 1993.

49. "Yejong sillok 睿宗實錄 [Annals of Yejong]." Chosŏn wangjo sillok 8.

50. Yi Chŏngil 이정일. "15 segi huban Chosŏnŭi sŏbungmyŏn pangŏwa Myŏngŭi Yodong chinch’ul” 15세기 후반 조선의 서북면 방어와 명의 遼東 진출 [The Chosŏn’s Defense Policy in the Southwest and the Ming’s Expansion to Liaodong in the Late Fifteenth Century]. ]." Yŏksawa tamnon 역사와 담론 87 July;(2018): 115–58.

51. Yi Chŏnggwi 李廷龜. "Wŏlsa sŏnsaeng chip 月沙先生集 [Collection of Master Wŏlsa]." Han’guk yŏktae munjip ch’ongsŏ 韓國歷代文集叢書. [Collected Works of Korea Through the Ages]. 236. Seoul: Han’guk munjip p’yŏnch’an wiwŏnhoe, Kyŏngin munhwasa, 1999.

52. Yongman chido 龍灣地圖. [Map of Yongman]. National Library of Korea, 2702–81.

53. "Yongmanji 龍灣志 [Gazetteer of Yongman]." Changsŏgak K2–4280

54. "Yŏnsan’gun ilgi 燕山君日記 [Diaries of Yŏnsan’gun]." Chosŏn wangjo sillok 12–14.

55. Yu Chaech’un 柳在春. "15 segi Myŏngŭi tongp’alch’am chiyŏng chŏmgŏwa Chosŏnŭi taeŭng” 15세기 명의 동팔참 지역 점거와 조선의 대응 [The Ming’s Occupation the “Eight Posts” Region and the Chosŏn’s Response]. ]." Chosŏnshidaesa hakpo 조선시대사학보 18 September;(2001): 5–34.

56. Zhang Shizun 張士尊. Mingdai Liaodong bianjiang yanjiu 明代遼東邊疆研究. [Study of the Liaodong Border in the Ming Dynasty]. Changchun: Jilin renmin chuban she, 2002.

57. Zhang Cunwu 張存武. "Mingji Zhong Han dui Yalu jiang xiayou daoyu guishuquan zhi jiaoshe” 明季中韓對鴨綠江下游島嶼歸屬權之交涉 [The China-Korea Negotiation on the Ownership of the Islands Downstream of the Yalu River in the Mid-Ming Period]." Hanguo xuebao 韓國學報 8 May;(1989): 8–19.

58. Zhao Shuguo 趙樹國. . Mingdai beibu haifang tixi yanjiu 明代北部海防體系研究. [Study of the Sea Defense System of North China in the Ming Dynasty]. Jinan: Shandong renmin chubanshe, 2014.

|

|