‘네트워크 분석’을 활용한 한국 고대사 연구의 새로운 방법론 모색 -동진∙16국 ~ 송∙북위 시기 교섭 데이터를 중심으로-

국문초록

네트워크 분석은 복잡한 사회 현상을 이해할 수 있도록 구성원 사이의 상호작용을 시각화하여 분석하는 방법론이다. 이것을 한국 고대사 연구에 접목한다면, 동진∙16국, 송∙북위 시기의 복잡한 교섭 네트워크를 분석하여 백제와 고구려의 역사적 위상을 조명할 수 있다. 기존 연구들은 백제, 고구려와 중국의 교섭에 초점을 맞추었고, 이 시기 동아시아 교섭 네트워크를 시각화하거나, 전체 교섭 네트워크 속에서 백제와 고구려의 위치를 비교한 연구는 거의 없었다. 이 논문에서는 고대 동아시아 교섭 데이터를 대상으로 네트워크 분석을 시도할 수 있는 방법론을 살펴보고, 특정 시공간의 교섭 데이터에 대한 시론적인 분석을 수행하고자 한다. 네트워크 분석을 고대사 연구에 적용하려면, 연구 적합성 검토, 데이터 수량 체크 및 추출, 데이터 신뢰도 검증, 데이터 분석 및 시각화와 의미도출 등의 단계가 필요하다. 고대사 연구에서 네트워크 분석을 활용할 때, 데이터 수량의 확보, 신뢰도의 검증 등이 한계로 대두된다. 고대 동아시아 교섭 데이터는 다른 기록보다 상대적으로 수량이 많으므로, 네트워크 분석을 활용하기에 적합하다. 하지만 교섭 데이터는 다양한 주체들의 입장에서 기록되므로, 고대사 연구자에 의한 데이터 신뢰도 검증이 필수적이다. 이 논문에서는 고대 동아시아 교섭 데이터 가운데 동진∙16국, 송∙북위 시기 교섭 데이터를 시론적으로 분석하였다. 분석 결과, 동진이 가장 높은 중심성 수치를 보였고, 그 뒤로 고구려와 백제가 위치하였는데, 백제의 중심성 수치는 특히 동진과의 교섭에 집중한 결과였다. 송과 북위 시기 교섭 빈도 데이터에 대한 네트워크 분석 결과, 송과 북위의 중심성이 28개 국가 중에 가장 높았고, 고구려, 토욕혼, 백제의 중심성도 두드러졌다. 교섭 경로 분석에서는 송이 가장 높은 매개 중심성을 지녔고, 고구려는 신라로 이어지는 통로 역할을 했으며, 백제는 마한, 가야, 왜로 가는 경로를 통제하는 정보의 흐름을 확인하였다. 백제는 고구려에 비해 중심성은 낮았지만, 여러 지역을 연결하는 매개자로서 중요한 역할을 하였다. 결론적으로 이 논문은 고대 동아시아 교섭 데이터를 대상으로 네트워크 분석을 적용할 수 있는 방법론을 모색하였으며, 시론적으로 특정 시기의 교섭 데이터를 분석하여 고대 동아시아 교섭 네트워크에 대한 구조적 이해를 시도하였다.

주제어: 네트워크 분석, 교섭, 백제, 고구려, 동진, 16국, 송, 북위, 중심성

Abstract

Network analysis is a methodology that helps understand complex phenomena by visualizing member interactions. In the context of Eastern Jin, Sixteen Kingdoms, Song, Northern Wei period, network analysis can shed light on the position of Paekche and Koguryŏ by analyzing negotiation networks. While existing studies have focused on negotiations between these states and China, few have visualized the entire negotiation network or compared the positions of Paekche and Koguryŏ within the broader East Asian network. This paper explores the network analysis methodology for ancient East Asian negotiation data and conducts a pilot analysis of specific periods.

The methodology for applying network analysis to ancient history involves several steps, including evaluating its suitability, quantifying the data, verifying data reliability, and analyzing and visualizing the data. Limitations of using network analysis to study ancient history include obtaining sufficient data and verifying data reliability. Ancient East Asian negotiation data is relatively more abundant than other records, making it a good candidate for network analysis. However, because negotiation data is recorded from the perspective of various actors, it is essential to verify the reliability of the data by ancient history researchers.

This paper theoretically analyzes the negotiation data of the Eastern Jin, Sixteen Kingdoms, Song, and Northern Wei periods. The negotiation network analysis reveals that Eastern Jin is the most centralized country, with Koguryŏ actively engaging in negotiations and Paekche focusing on diplomacy with Eastern Jin. The centrality analysis on the negotiation frequency data during Song and Northern Wei period shows that the Song and Northern Wei had the highest centrality in negotiation frequency among 28 countries, with Koguryŏ, Tuyuhun, and Paekche also prominent. The negotiation route analysis reveals the flow of information, with the Song having the highest betweenness centrality, Koguryŏ serving as a conduit to Shilla, and Paekche controlling the route to Mahan, Kaya, and Wa. Paekche plays a crucial role as a conduit between various regions, despite having lower centrality than Koguryŏ.

In conclusion, this paper explored the methodology of applying network analysis to ancient East Asian negotiation data and attempted to understand the structural structure of ancient East Asian negotiation networks by analyzing negotiation data from a specific time period.

KeyWords: Network analysis, Negotiation, Paekche, Koguryŏ, Eastern Jin, Sixteen Kingdoms, Song, Northern Wei, Centrality

Introduction

Network analysis is a widely used data analysis methodology in sociology, providing visualizations of interactions among members to aid in understanding the structure of various phenomena. 1 It proves particularly effective when dealing with large datasets that present challenges in gaining a comprehensive structural understanding or analyzing complex interrelationships between multiple members. Attempts to utilize network analysis in the study of Korean history began in the field of medieval and modern history, and archaeology is also increasingly incorporating network analysis. Internationally, network analysis methodologies have been more commonly employed in archaeological and ancient history research since the 2000s. In comparison, the movement to apply network analysis to Korean ancient history research started relatively late. While a few studies have employed network analysis on keywords of ancient Korean history extracted from research papers and history textbooks, there have been limited attempts to extract data from ancient historical documents for network analysis.

As pointed out in the previous studies, the fundamental limitation of ancient history research is the lack of historical record. Therefore, it is difficult to obtain enough data for network analysis. 2 In the network analysis study of Korean ancient history, focusing on articles, textbooks, etc. rather than written sources was thought to be a break-through to overcome this limitation. However, it is thought that textual materials, which is continuously being excavated, and negotiation records, which are accumulated in a directional manner, will provide a relatively large amount of data. In the context of ancient East Asia, negotiations refer to the political and diplomatic relations between countries, and these records were documented in diplomatic protocols through the movement of envoys, specifically within the tribute system. Since the negotiation records were repeatedly recorded in a directional form of data, it is thought to be a suitable source of literature to attempt quantitative analysis through network analysis. Network analysis can be a useful methodology for visualizing pluralistic negotiation networks and quantitatively analyzing the centrality of participants, particularly in cases involving multiple states with complex interrelationships. During the Eastern Jin, Sixteen Kingdoms, Song, and Northern Wei period, there was a proliferation of pluralistic negotiations involving numerous. 3 Existing Korean studies have also pointed out that the international order in East Asia during this period was a multi-layered and pluralistic center-periphery relationship mediated by ‘Chinese consciousness’ and ‘Tribute(Chaogong, 朝貢) and Cefeng(冊封)’. 4 To analyze the multiple center-periphery relationships that operated within a large negotiation network, network analysis methodologies that structure and visualize the interactions of pluralistic actors are effective. In addition, from the perspective of Korean history, this was a period when Paekche and Koguryŏ were active in the pluralistic East Asian order, negotiating with both the Southern and Northern Dynasties. Therefore, visualizing of the East Asian negotiation network during this period becomes essential for examining the positioning of Paekche and Koguryŏ within East Asia.

Existing studies have summarized the negotiations between Paekche, Koguryŏ, and China during this period and derived their political and historical implications, 5 and more recently, they have synthesized the political changes and foreign policies of Paekche, Koguryŏ, and Chin a. 6 However, there have been few attempts to visualize the entire negotiation network during this period and analyze the position of Paekche and Koguryŏ in it. Existing studies have focused on the history of foreign relations between Paekche, Koguryŏ and China from a Korean perspective, but it is also imperative to compare and examine the position of Paekche and Koguryŏ within the negotiation network of East Asia as a whole. To date, only a limited number of studies have ventured into conducting network analysis on negotiation data from ancient Korea or ancient East Asia. Thus, this article aims to explore the application of network analysis methodology to ancient East Asian negotiation data for the study of Korean ancient history. Given that the primary objective of this article is to delve into the network analysis methodology for ancient East Asian negotiation data, it does not delve into the standardization work considering the duration of state existence and frequency of negotiations by country, or the time series analysis show-casing changes in political conditions and negotiation patterns. These detailed analyses will be addressed in a separate paper.

Concepts and Research Trends in Network Analysis

Network analysis is a methodology for quantitatively analyzing and visualizing the relationships and centrality of network participants. 7 In this approach, a network refers to a web-like structure where nodes are connected. Within the Korean sociological community, the methodology of ‘social network analysis’ emerged in the 1980s 8 and gained attention in the 2000s to explore the ‘networked society’ that arose amidst the collapse of the nation-state, the emergence of postmodern discourse, and the dissolution of boundaries. 9

In network analysis, the objects of analysis are called nodes or actors and the connections between them are called links, lines, or edges. The analysis process involves creating a matrix of nodes and links and visualizing patterns or arrangements within the network.

One of the key concepts in network analysis is centrality which measures the influence of a node. Centrality can be categorized into different types, including degree centrality, closeness centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality. Degree centrality refers to the degree of connection between a node and other nodes, and the number of directly connected neighbors indicates the amount of influence. Inward connections to a node are called in-degree centrality, and outward connections are called out-degree centrality.

Closeness centrality is a measure of a node’s centrality in the overall network structure: the node with the smallest sum of the shortest distances connecting two nodes has the highest closeness centrality in the entire network. In other words, it’s a way to figure out who in the network’s structure you can get information through the fastest.

Betweenness centrality is a way of identifying intermediary roles, measuring how many times a node is included in the shortest path between other nodes, which reveals its control over the flow of information and the dependency of other nodes. It’s a way to determine who is most needed to relay information. Eigenvector centrality is the degree to which a node is chained to its neighbors with a high degree of connection centrality.

Western archaeological research applying network analysis has surged since the late 2000s, 10 coinciding with the rise of social network analysis and the ubiquity of network analysis tools such as UCINET. 11 Network analysis methodologies have gained traction in archaeological research because they are effective in combining with geographic information systems (GIS), representing temporality, and analyzing networks of relationships between artifacts. 12

The application of network analysis in Western archaeology and ancient history research can be categorized into three types of data: geographic data, material data, and literary data. Recent studies have tried to incorporate time-series changes into the data analysis process, paying attention to temporal fluctuations through multiple network snapshots. 13 For instance, in the field of Roman history, researchers have analyzed regional transportation networks based on material, geographical, and literary data, which reveal transportation networks at the village level. 14 Similarly, in the context of East Asian ancient history, it is also possible to analyze networks at the national or regional level based on records of negotiations between countries documented in historical texts or foreign artifacts at port sites along coastal routes. Compared to archaeology, there are relatively few studies of network analysis in Western antiquity based on written sources. Recent studies include one that analyzed the relationship between ancient Greek city-states and their colonies, 15 and another that discussed the problems and strategies for using SNA (Social Network Analysis) in ancient studies. 16 In the latter paper, the main problem of SNA research in ancient history is the quantity and reliability of data. This study suggests that the problem of data quantity should be solved by utilizing excavated documents along with material and geographical data, and the problem of reliability should be solved by historical criticism and interpretation of historical context by ancient researchers. In Korea, the archaeological community has increasingly focused on network analysis since 2019, with active research being conducted on network analysis of Bronze Age settlements, 17 Neolithic pottery, 18 foreign artifacts in the Yŏngnam region, 19 Nangnang Tombs artifacts, 20 material culture of the Yŏngsan’gang River basin, 21and theoretical reviews. 22 These studies have greatly helped to understand the relationship between villages or ruins with different hierarchies, or the network in which foreign artifacts are distributed in certain areas. In the field of ancient history, there were attempts to analyze North Korean papers using Semantic network analysis to organize North Korea’s research trends of Parhae history, 23 or to quantitatively analyze keywords of Korean ancient history papers after liberation and compare them with existing conclusions that analyzed research trends qualitatively. 24 In 2022, studies were published that reviewed the recognition of Kaya in social media and Korean history textbooks through text network analysis methods. 25 These research efforts primarily focus on analyzing texts such as research papers, social media, and textbooks, aiming to explore historiographical approaches and current historical awareness reflected in these diverse modern sources. In terms of network analysis of ancient historical documents themselves, a theoretical attempt was made to analyze the village name data of the wooden tablets of Haman Sŏngsansansŏng castle. 26 Additionally, a preliminary attempt at network analysis of ancient East Asian negotiation data was conducted in a study on the Paekche maritime network. 27

Attempts to use network analysis in the study of Korean medieval and modern history began relatively early. For example, in the field of medieval history, efforts have been made to explore methodologies for analyzing medieval literary data in terms of ‘Korean history big data’ and visualizing networks between historical figures. 28 In the study of modern history, text network analysis has been used to analyze the connections between vocabulary in modern newspapers and magazines. 29 In sociology, a study was submitted that analyzed the network of independence activists from 1895 to 1945 using the approach of historical sociology. 30

Network analysis is a quantitative analysis methodology that visualizes the interrelationships of members and provides a structural understanding of a particular phenomenon. In Western archaeology and ancient history, interest in network analysis has surged since the late 2000s. In Korean history, network analysis has been employed in the fields of medieval history, modern history, and historical sociology. Notably, the application of network analysis in archaeological research has experienced significant growth since 2019. In the study of Korean ancient history, network analysis has been used for historical analysis of research papers, the examination of historical perceptions in history textbooks, and pilot analysis of excavated textual materials such as wooden tablets. In the following chapter, I will synthesize these analyses and draw implications and methodologies for applying network analysis in Korean ancient history studies, and specifically describe an approach for analyzing negotiation data.

Methodology for Network Analysis of Ancient East Asian Negotiation Data

Considering the concept of network analysis described above and the trend of its application in Korean history research, the following implications can be drawn for the application of network analysis to Korean ancient history. First, integrate and utilize ancient material, literary, and geographical data. Second, the collected data should be made publicly available in the form of an Open Access DB; third, researchers’ participation is essential for historical criticism and interpretation of the historical context; and fourth, researchers should pay attention to excavated textual materials and negotiation records to increase the quantity of data. Fifth, network analysis requires a diachronic view. 31

Network analysis-based digital historiography, which targets literary sources, requires a comprehensive understanding of quantitative and qualitative analysis (historical criticism) methodologies and the context of the entire history, and follows the flow of ‘data collection, data input, text mining, DB construction, statistical analysis, and visualization analysis’. 32 Quantitative analysis using digital technology in history has problems such as differentiation from qualitative analysis conclusions and limitations in data quantification. Researchers need to quantify data through rigorous source criticism, utilize statistical analysis methodologies, and present contextualized explanations that consider temporality and causality to suit their research topics and goals. 33

Therefore, the methodology for applying network analysis to the study of ancient history is as follows. First, the researcher should examine whether the network analysis methodology is appropriate for the content and purpose of the study, and whether it is suitable for exploring the inherent value of history. Second, the researcher examines whether the quantity of data under study is sufficient or likely to increase in the future, and whether meaningful analysis is possible even if the quantity is relatively small. Then, we quantify the data in the historical records and process it into a form that fits into a network analysis program. Third, verify the reliability of the data by critiquing the data. Even in the general process of big data processing, training on biased data leads to inaccurate results, so it is important to secure many unbiased training data. The participation of a historian who understands historical methodology and the context of the source material is essential to verify data reliability. Reliability verification can precede or coincide with the data extraction process, but it requires prerequisites such as critiquing the sources and understanding the context of the negotiations, so the final verification process is necessary after the data extraction is completed. Fourth, the researcher analyzes the data using a suitable program and considers whether there are implications beyond or complementary to existing qualitative analysis studies. In this process, it is also necessary to validate and interpret the results of the quantitative analysis through qualitative analysis of the context of historical texts.

Next, this study will discuss specifically how to approach ancient East Asian negotiation data with a network analysis methodology.

In Korean ancient history research, network analysis has been attempted in the analysis of texts in papers, textbooks, and social media, and has also been piloted in the analysis of excavated texts. When applying network analysis methodologies to the study of ancient history, one of the key issues is the quantity of data. When analyzing data using digital technology, the way to increase the reliability of the results is to have many unbiased data. In a study on AI reading of ancient Korean wooden tablets, it was mentioned that the accuracy of the system can be improved by dramatically increasing the amount of training data through spatial expansion (Korean, Chinese, and Japanese texts) and temporal expansion (Koryo and Chosŏn dynasties). 34

In addition to excavated texts, another relatively quantitative source of data in ancient history is negotiation data. They are written records of political, diplomatic, and military “negotiations” between states. These ancient East Asian negotiation data are mostly recorded in the form of directional data, meaning they have clear senders and receivers.

Some efforts have been made to quantify and chart negotiation data over a specific spatial and temporal range in a directional manner, for example, studies that have charted negotiation and warfare data from the Southern and Northern dynasties periods. 35 However, these studies have not reached the stage of effectively visualizing the negotiation network in East Asia at the time and quantitatively analyzing the centrality of specific countries. Full-scale network analysis of negotiation data was first attempted in the study of maritime networks during the Paekche Hansŏng (漢城) period. This study examines the status of Paekche through network analysis of East Asian negotiation data during the Song and Northern Wei periods and sets the research process as ‘analytical problem posing’ → ‘network data investigation’ → ‘network creation’ → ‘network analysis execution’. 36 ‘Raising analytical issues’ corresponds to the first step of the research suitability review in 〈 Table 1〉, ‘Investigating network data’ corresponds to the second step of data extraction, and ‘Creating networks’ and ‘Running analyses’ correspond to the fourth step of data analysis. This article extends the existing research by setting data reliability verification as a step 3 and mentions the steps for ancient history researchers to understand the context of historical documents and reduce the bias of extracted data through the methodology of historical criticism. In conclusion, we can specify the methodology for network analysis of ancient negotiation data as follows. First, it is necessary to determine whether the negotiation data in a certain time and space is suitable for quantitative analysis methodology such as network analysis. Second, the negotiation data should be extracted from various history books in China and neighboring countries. Third, the researcher should verify the reliability of the data by applying extraction criteria that align with the characteristics of each period and the context of the historical sources. This step involves understanding the historical context surrounding the negotiation records. Fourth, the researcher analyzes the extracted negotiation data and visualizes it in an appropriate way to pursue structural understanding.

Pilot Analysis of the Negotiation Network during Eastern Jin-Sixteen Kingdoms and Song-Northern Wei period: Examining the Status of Paekche and Koguryŏ

1) Analysis of the Eastern Jin-Sixteen Kingdoms Period Negotiation Network

The temporal scope of the negotiation data analyzed in this chapter focuses on the Eastern Jin period (317–420), while the spatial scope encompasses the Eastern Jin dynasty, all the countries in the Huaibei region, and the neighboring states engaged in negotiations with them. This period was a pluralistic order in which the unified dynasties collapsed, and neighboring peoples established multiple states in the Zhongyuan region, so the interactions between the Eastern Jin and the Sixteen Kingdoms, as well as with other countries outside the region, were very complex. 37 Therefore, the negotiation data of this period is well suited to be examined by network analysis, which structures and visualizes the interrelationships of actors. In addition, since there were hundreds of negotiations conducted by dozens of actors, the amount of data required for analysis can be secured. However, since there are various variables such as negotiations during the process of independence as a country, independent activities of local officials belonging to national units, and self-designation of various officials, it is necessary to verify the reliability of individual data by historical researchers. In accordance with the intention of this article to explore the methodology of analyzing negotiation data, it is not possible to cover all the detailed reliability verification procedures. A subsequent paper will present comprehensive extraction criteria and reliability verification procedures. Below, I present the extracted data and the results of the network analysis to explore the position of Paekche and Koguryŏ in the overall negotiation network of East Asia during this period.

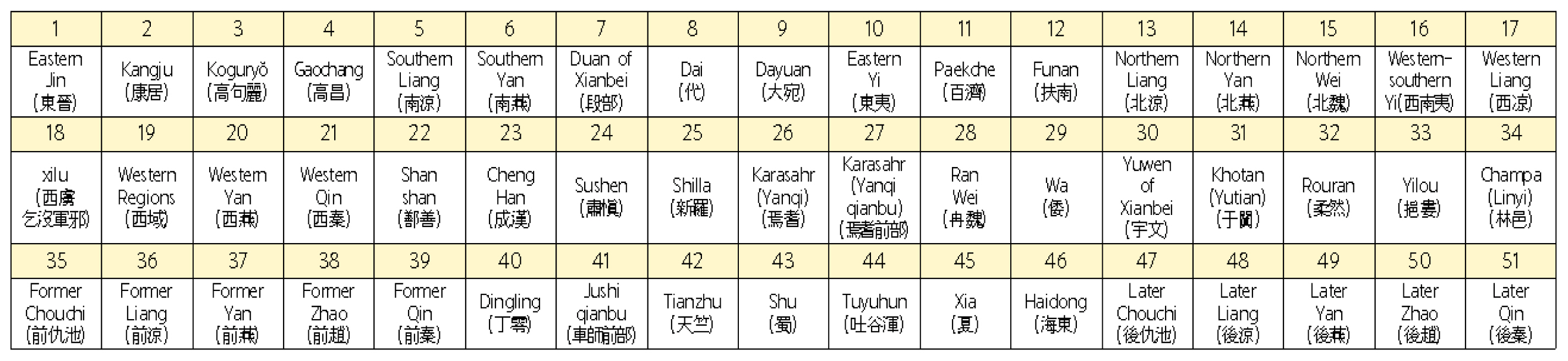

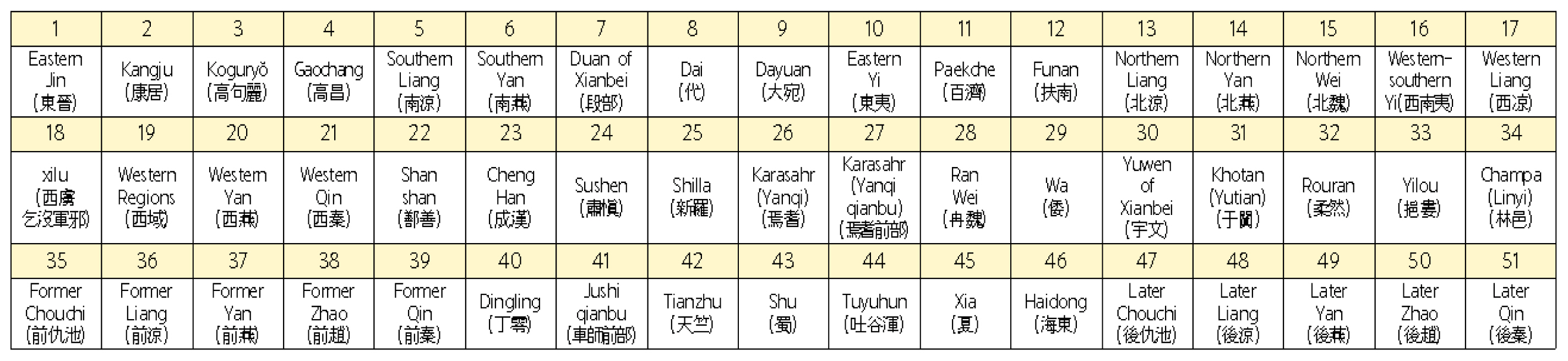

The negotiation data extracted during this period was organized in the form of an Excel file. The negotiation data file was reprocessed into a matrix suitable for network analysis programs (〈 Annex Table 1〉). The negotiation data matrix was calculated for centrality through the UCINET 6.730 program and visualized through the linked Netdraw program. The table below shows the results of the centrality analysis (〈 Table 2〉), and the graph below shows the combined visualization of the matrix and centrality analysis results (〈 Figure 1〉). Since this paper aims to present a methodology for analyzing ancient East Asian negotiation data and to try to analyze some networks in a theoretical way, the full network analysis graph is not presented, and only the out-degree centrality graph, which shows the characteristics of individual nodes, is analyzed in a theoretical way. This is because out-degree centrality shows the active connection intentions of the negotiation states, such as Paekche and Koguryŏ. Detailed analyses will be conducted in other papers in the future. In the graph, the size of each node (representing a country) corresponds to its outdegree centrality. Outdegree centrality is determined by the number of outgoing connections from a node to other nodes, while indegree centrality is based on the number of incoming connections to a node from external sources. The color of the nodes is based on the results of the K-core analysis: red, gray, blue, and black depending on the connectivity of the nodes. The thickness of the arrows is tied to the frequency of negotiation, and the thickness of the arrow heads is a combination of directionality. The location of the nodes is based on the location of each country’s center, but in some cases, they are slightly different from their original positions for visual effect.

The combined analysis of the graphs and centrality measurements reveals that, overall, the Eastern Jin dynasty emerges as the most centralized country within the negotiation network, displaying extensive connections to other nodes. This finding aligns with expectations, considering that the negotiation data is predominantly derived from the Book of Jin, which extensively covers the Western and Eastern Jin period. In addition, the various dynasties in Huaibei were relatively short-lived, growing rapidly and then declining or collapsing quickly, so they accumulated less negotiation data than Eastern Jin, which lasted for more than 100 years. However, despite their short existence, Later Zhao, Former Yan, Former Qin, and Later Qin have relatively high centrality values, likely because they were the states that dominated or temporarily hegemonized Huaibei.

During the Eastern Jin, Sixteen Kingdoms and Paekche, Koguryŏ were engaged in frequent negotiations that are difficult to compare with Shilla and Wa. Koguryŏ was actively engaged in negotiations with neighboring states in the Huabei region, such as Former Yan, Former Qin, Later Zhao, Southern Yan, Later Yan, and Northern Yan, and negotiated with Eastern Jin across the sea. Koguryŏ’s out-degree centrality ranked fourth, after Eastern Jin, Later Qin, and Fomer Liang, but higher than that of Former Qin, Former Yan, Northern Wei, and Later Zhao. Koguryŏ outlasted these dynasties and appears to have been proactive in responding to changes in Chinese politics. It also ranks seventh in terms of closeness centrality, a measure of how close it is to the center of the entire network, higher than Western Qin, Northern Wei, and Later Yan. Koguryŏ had considerable centrality in the East Asian negotiation network during this period, as it negotiated with all its geographically close neighbors, including Later Zhao, Former Yan, and Former Qin, as well as with the major states that dominated the negotiation network in the North China region, and across the sea to Eastern Jin in Jiangnan. However, its in-degree centrality ranks 11th, suggesting that envoys from the Chinese dynasties reached it with relatively less frequency than Koguryŏ did.

Paekche presumably engaged with several dynasties in Huaibei, but there is no official data on state-to-state negotiations. Rather, Paekche focused on diplomacy with Eastern Jin, which it did more frequently than Koguryŏ after 372. Paekche’s out-degree centrality ranking is 11th, lower than that of Koguryŏ, which actively negotiated with the Huaibei dynasty, but higher than that of Huaibei dynasties such as Later Liang and Later Yan, as well as Shilla and Wa. Paekche is presumed to have maintained considerable centrality by continuing negotiations with the Eastern Jin

Comparing Koguryŏ and Paekche to other states during the same period, Koguryŏ ranks 7th in closeness centrality, surpassing Western Qin, Later Yan, and Northern Liang. On the other hand, Paekche falls outside the top 20, but it ranks higher than Cheng Han, Champa, Wa, and several states in the western region. Paekche was somewhat far from the center of the network because it did not have formal negotiations with the dynasties in the Huaibei region, but Koguryŏ is thought to have been relatively close to the center of the entire network because it had an active negotiation network with the more central Eastern Jin, Former Qin, Later Zhao, and Former Yan.

Examining the betweenness centrality ranking, which identifies the role of brokers, Koguryŏ ranks 6th, while Paekche ranks 10th, indicating relatively high positions. Koguryŏ engaged in negotiations with various nodes such as Eastern Jin, the various dynasties in Huaibei, and Shilla. Paekche’s high ranking in betweenness centrality can be attributed to its frequent negotiations with Eastern Jin in particular. However, the above analysis is limited by the fact that Paekche and Eastern Jin’s negotiations were concentrated after 372, and we did not consider a standardization method to compensate for the differences in the length of existence of various countries. These limitations can be overcome through time-series analysis methods, which will be examined in detail in a forthcoming paper.

2) Analysis of the Song-Northern Wei Period Negotiation Network

After the fall of the Eastern Jin, the Song took control of the Jiangnan region, and around the same time, the Northern Wei unified Huaibei. Negotiations during this period were reorganized around the Southern and Northern dynasties, but still maintained a pluralistic order, with many peripheral countries negotiating with the Southern, Northern, or both dynasties. Consequently, a comprehensive network analysis is essential to enhance the structural understanding of the negotiation network during this period. 38

The temporal scope of the negotiation data extracted in this section is the period of Song’s existence (420–479), and the spatial scope is the entirety of the Northern and Southern dynasties and the neighboring countries that negotiated with them, like the analysis in the previous section. The negotiation data is based on the negotiation tables of this period compiled by existing studies, 39 and is extracted in a directional form from historical sources such as The Book of Song, Book of Sui, and History of the Three Kingdoms (Samguksaki), The Chronicles of Japan (Nihonshoki). The matrix that processed the negotiation data into a form that allows network analysis is as follows (〈 Table 3〉). This data matrix was utilized to calculate centrality figures using UCINET 6.730 (〈 Table 4〉) and visualized using Netdraw (〈 Figure 2〉). The centrality of Song and Northern Wei was found to be the highest when analyzing the frequency of negotiations among the 28 countries that negotiated with Song and Northern Wei. This is not surprising since the frequency of negotiations was extracted mainly from the Book of Song and Wei. However, it also shows that Song and Northern Wei were indeed the most prominent sources of advanced texts and diplomatic targets in East Asia. In addition to Song, Koguryŏ, Northern Wei, and Tuyuhun, the top 10 countries in terms of out-degree centrality include Paekche at #8, and the top 10 countries in terms of in-degree centrality are similar. Paekche was analyzed to have maintained a certain centrality between Song and Northern Wei during the early North-South period, following Koguryŏ and Tuyuhun.

However, it is difficult to accurately determine Paekche’s status based on the frequency graph and centrality analysis alone. In the graph, the arrows directly connect the negotiation between Wa and Song, but the actual historical records show that the envoy of Wa King Bu(武) actually arrived in China through Paekche. 41 This limitation is also confirmed in the analysis of the negotiation network during the Eastern Jin and Sixteen Kingdoms. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the negotiation route data separately, and the matrix below is the result of analyzing only the nine countries connected to Song through the sea (〈 Table 5〉). The numbers in the data matrix quantify the value of connections to other nodes (countries) that a particular node (country) expects from its neighbors. For example, the connection value from Song to Paekche was set to four countries: Paekche, Mahan, Kaya, and Wa. The graph below is a visualization of the negotiation path data matrix using UCINET’s Netdraw program (〈 Figure 3〉). This is a directed graph of the link data, where the thickness of the links and arrows is proportional to the value of a node’s connection to another node in the negotiation path. The size of the nodes is set to be proportional to their betweenness centrality. Since betweenness centrality is an indicator of control of information connections and dependence on other nodes, it would be most effective to visualize ancient East Asian negotiation routes data. Song had the highest betweenness centrality, which is the same as what we saw in the negotiation frequency graph, indicating that it controlled the flow of information in East Asia. Koguryŏ has the second highest betweenness centrality after Song, as it was connected to Paekche, Kaya, and Wa, and served as a conduit to Shilla. Paekche is ranked after Song and Koguryŏ in terms of betweenness centrality because it controlled the route from Song to Paekche to Mahan, Kaya, and Wa.

The thickness of the lines and arrows in the link data indicate the value of the connections to other nodes. In the case of Paekche, it virtually monopolized the route between Mahan and China, so Mahan’s dependence on Paekche to negotiate with China was maximized. Wa had to go through Kaya to negotiate with Song, and Kaya had to go through Mahan, so the arrow thickness in each direction is thicker. This route analysis is not a strictly quantitative analysis in that the connections in the data are based on the researcher’s qualitative analysis of the international situation and routes at the time, but it complements the results of the network analysis of the negotiation data.

From the above analysis, we can see that Paekche was one level below Koguryŏ in terms of centrality in East Asian negotiations, being connected to both Song and Northern Wei. Although Paekche was lower than Koguryŏ in terms of degree centrality of negotiation frequency and betweenness centrality of negotiation routes, it seems to have played its role as a conduit between Mahan, Kaya, Wa, and China.

Conclusions

Network analysis, a methodology used in sociology and history, helps understand complex phenomena by visualizing member interactions, particularly in cases with large data or complex relationships. In the context of East Asia during the Eastern Jin, Sixteen Kingdoms, Song, and Northern Wei period, network analysis can be useful in analyzing pluralistic negotiation networks and the centrality of participants, shedding light on the position of Paekche and Koguryŏ in the region. Although existing studies have examined the negotiations between these states and China, few have visualized the entire negotiation network or compared the position of Paekche and Koguryŏ within the broader East Asian network. This paper aims to explore the network analysis methodology for ancient East Asian negotiation data and conducts a pilot analysis of negotiation data from specific periods. However, more detailed analyses regarding negotiation standardization, duration, frequency, political changes, and patterns will be addressed in a separate paper.

Network analysis is a methodology used to quantitatively analyze and visualize relationships and centrality in a network. It has gained attention in various fields, including sociology, archaeology, and history. Western archaeology and ancient history have seen a surge in network analysis, particularly in the analysis of geographic, material, and literary data. In the Korean context, network analysis has been applied in the study of medieval and modern history, as well as in archaeological research since 2010s. Network analysis has been utilized to study Bronze Age settlements, Neolithic pottery, foreign artifacts, and ancient historical documents. The field of medieval history has explored methodologies for analyzing literary data, while modern history has focused on analyzing relationship networks in documents. Korean ancient history studies began to utilize network analysis methodologies relatively late, with historical analyses of research papers or history textbooks, and theoretical attempts to analyze wooden tablets. Considering the environment of Korean ancient history research, where there are relatively few historical records, the accumulated negotiation data between countries within a certain spatial and temporal range would be a good source for network analysis.

The methodology for applying network analysis to ancient history involves several steps. Firstly, the researcher evaluates whether network analysis is appropriate for the study’s content and purpose. Secondly, the data is quantified and processed to fit into a network analysis program. Thirdly, data reliability is verified by critiquing the sources and understanding the historical context. Participation of a historian is crucial for this step. Fourthly, the researcher analyzes the data using a suitable program and considers whether there are implications beyond to existing qualitative analysis studies. For the specific case of network analysis of ancient negotiation data, the methodology involves determining the suitability of the data for quantitative analysis, extracting the negotiation data from historical sources, verifying data reliability, and analyzing and visualizing the data to gain structural understanding.

This paper firstly focuses on the negotiation data of the Eastern Jin period (317–420). The complex interactions between Eastern Jin, Sixteen Kingdoms, and other countries are suitable for network analysis. The negotiation data was extracted, organized in an Excel file, and analyzed using network analysis programs. The centrality analysis and visualization of the negotiation network reveal that Eastern Jin is the most centralized country. Koguryŏ had high centrality, actively engaging in negotiations with neighboring states and Eastern Jin. Paekche focused on diplomacy with Eastern Jin and had relatively high centrality. When compared to other states, Koguryŏ ranked higher in centrality measures such as closeness and betweenness. However, this analysis has limitations in that the standardization of the negotiation frequency and diachronic review have not been completely made. Therefore, a separate paper in the future will supplement the limitations by applying the time-series analysis methodology.

After the Eastern Jin’s fall, the Song controlled the Jiangnan region, while the Northern Wei unified Huaibei. Network analysis was used to understand the negotiations during this period. The temporal scope of the negotiation data is the period of Song (420–479), and the spatial scope is the entirety of the Northern and Southern dynasties and the neighboring countries that negotiated with them. The centrality analysis showed that the Song and Northern Wei had the highest centrality in terms of negotiation frequency among the 28 countries. Koguryŏ, Tuyuhun, and Paekche were also prominent in terms of connectivity. Paekche maintained relatively high centrality between Song and Northern Wei during the early North-South period. In order to understand the centrality that is not revealed only by analyzing the frequency of negotiations, the analysis of the negotiation route at that time was also conducted. Analyzing the negotiation route data matrix revealed that Song had the highest betweenness centrality, controlling the flow of information. Koguryŏ served as a conduit to Shilla, while Paekche controlled the route from Song to Mahan, Kaya, and Wa. The negotiation route analysis complemented the network analysis results. Overall, Paekche played a role as a conduit between Mahan, Kaya, Wa, and China, although it had lower centrality than Koguryŏ.

In conclusion, this paper extracted East Asian negotiation data from historical sources during the Eastern Jin, Sixteen Kingdoms, Song, and Northern Wei periods and attempted structural understanding through network analysis. Through this, this paper attempted to present a network analysis methodology of ancient East Asian negotiation data. Ancient East Asian diplomatic records are considered suitable materials for network analysis in the context of literature data from ancient history studies that are difficult to extract sufficient data for quantitative analysis.

Figure 1

Negotiation graph of Eastern Jin and Sixteenth Kingdom (outdegree centrality)

Figure 2

Negotiation frequency graph of Song and Northern Wei period 40

Figure 3

Negotiation route graph of Song and neighboring countries 43

Table 1

A typical process for studying ancient history with network analysis.

|

① |

→ |

② |

→ |

③ |

→ |

④ |

|

Study suitability review |

Checking data quantities and extracting |

Verify data reliability |

Data analysis, visualization, interpretation of results |

Table 2

Centrality analysis results of Eastern Jin and the Sixteenth Kingdom negotiation data

|

Name |

Out degree Centrality |

|

Eastern Jin |

0.8 |

|

Later Qin |

0.52 |

|

Former Liang |

0.42 |

|

Kogurŏ |

0.36 |

|

Former Qin |

0.34 |

|

Former Yan |

0.32 |

|

Northern Wei |

0.26 |

|

Southern Liang |

0.24 |

|

Later Zhao |

0.24 |

|

Northern Liang |

0.22 |

|

Paekche |

0.16 |

|

Later Liang |

0.16 |

|

Later Yan |

0.16 |

|

Western Qin |

0.14 |

|

Linyi |

0.14 |

|

Later Chouchi |

0.14 |

|

Former Chouchi |

0.12 |

|

Dai |

0.12 |

|

Shilla |

0.1 |

|

Western Liang |

0.1 |

|

Shu |

0.1 |

|

Duan of Xianbei |

0.08 |

|

Southern Van |

0.08 |

|

Xia |

0.08 |

|

Former Zhao |

0.08 |

|

Shanshan |

0.08 |

|

Yutian |

0.08 |

|

Tuyuhun |

0.06 |

|

Western Regions |

0.06 |

|

Dayuan |

0.06 |

|

Western-southern Yi |

0.06 |

|

Sushen |

0.06 |

|

Ran Wei |

0.06 |

|

Western Yan |

0.04 |

|

Jushi qianbu |

0.04 |

|

Yuwen of Xianbei |

0.04 |

|

Eastern Yi |

0.04 |

|

Funan |

0.04 |

|

Haidong |

0.04 |

|

Yanqi |

0.04 |

|

Rouran |

0.04 |

|

Kangju |

0.02 |

|

Gaochang |

0.02 |

|

Cheng Han |

0.02 |

|

Northern Yan |

0.02 |

|

Dingling |

0.02 |

|

Tianzhu |

0.02 |

|

Wa |

0.02 |

|

Yilou |

0.02 |

|

Xilu |

0.02 |

|

Yanqi qianbu |

0.02 |

|

Name |

In-degree Centrality |

|

Eastern Jin |

1.22 |

|

Former Qin |

0.72 |

|

Later Qin |

0.68 |

|

Former Yan |

0.54 |

|

Northern Wei |

0.52 |

|

Former Liang |

0.44 |

|

Later Zhao |

0.44 |

|

Southern Liang |

0.22 |

|

Western Qin |

0.2 |

|

Later Yan |

0.18 |

|

Kogurŏ |

0.14 |

|

Northern Liang |

0.12 |

|

Cheng Han |

0.12 |

|

Paekche |

0.1 |

|

Later Liang |

0.1 |

|

Former Chouchi |

0.1 |

|

Northern Yan |

0.1 |

|

Tuyuhun |

0.08 |

|

Shilla |

0.06 |

|

Western Liang |

0.06 |

|

Southern Yan |

0.06 |

|

Former Zhao |

0.06 |

|

Later Chouchi |

0.04 |

|

Xia |

0.04 |

|

Western Yan |

0.04 |

|

Shu |

0.02 |

|

Duan of Xianbei |

0.02 |

|

Shanshan |

0.02 |

|

Western Regions |

0.02 |

|

Jushi qianbu |

0.02 |

|

Rouran |

0.02 |

|

Dingling |

0.02 |

|

Linyi |

0 |

|

Dai |

0 |

|

Yutian |

0 |

|

Dayuan |

0 |

|

Western-southern Yi |

0 |

|

Sushen |

0 |

|

Ran Wei |

0 |

|

Yuwen of Xianbei |

0 |

|

Eastern Yi |

0 |

|

Funan |

0 |

|

Haidong |

0 |

|

Yanqi |

0 |

|

Kangju |

0 |

|

Gaochang |

0 |

|

Tianzhu |

0 |

|

Wa |

0 |

|

Yilou |

0 |

|

Xilu |

0 |

|

Yanqi qianbu |

0 |

|

Name |

Closeness Centrality |

|

Eastern Jin |

0.649 |

|

Former Qin |

0.633 |

|

Later Zhao |

0.602 |

|

Former Yan |

0.543 |

|

Later Qin |

0.538 |

|

Former Liang |

0.532 |

|

Kogurŏ |

0.51 |

|

Western Qin |

0.495 |

|

Former Chouchi |

0.485 |

|

Sushen |

0.472 |

|

Northern Wei |

0.467 |

|

Later Yan |

0.455 |

|

Northern Liang |

0.446 |

|

Western-southern Yi |

0.446 |

|

Eastern Yi |

0.446 |

|

Western Liang |

0.435 |

|

Duan of Xianbei |

0.435 |

|

Shanshan |

0.435 |

|

Yutian |

0.435 |

|

Later Chouchi |

0.431 |

|

Dai |

0.427 |

|

Xia |

0.42 |

|

Shu |

0.42 |

|

Dayuan |

0.42 |

|

Tuyuhun |

0.41 |

|

Shilla |

0.41 |

|

Southern Liang |

0.407 |

|

Later Liang |

0.407 |

|

Former Zhao |

0.407 |

|

Western Regions |

0.407 |

|

Paekche |

0.403 |

|

Ran Wei |

0.403 |

|

Cheng Han |

0.397 |

|

Linyi |

0.397 |

|

Funan |

0.397 |

|

Wa |

0.397 |

|

Jushi qianbu |

0.391 |

|

Haidong |

0.391 |

|

Kangju |

0.391 |

|

Tianzhu |

0.391 |

|

Xilu |

0.391 |

|

Northern Yan |

0.388 |

|

Southern Yan |

0.385 |

|

Dingling |

0.379 |

|

Yuwen of Xianbei |

0.379 |

|

Yanqi |

0.379 |

|

Gaochang |

0.379 |

|

Yilou |

0.379 |

|

Western Yan |

0.36 |

|

Yanqi qianbu |

0.35 |

|

Rouran |

0.329 |

|

Name |

Betweenness Centrality |

|

Eastern Jin |

0.798 |

|

Former Yan |

0.606 |

|

Former Liang |

0.431 |

|

Former Qin |

0.379 |

|

Later Qin |

0.328 |

|

Kogurŏ |

0.32 |

|

Later Zhao |

0.307 |

|

Northern Wei |

0.264 |

|

Linyi |

0.223 |

|

Paekche |

0.169 |

|

Later Chouchi |

0.165 |

|

Former Chouchi |

0.129 |

|

Southern Liang |

0.129 |

|

Western Liang |

0.125 |

|

Dai |

0.124 |

|

Western Qin |

0.115 |

|

Northern Liang |

0.114 |

|

Later Yan |

0.107 |

|

Ran Wei |

0.088 |

|

Cheng Han |

0.086 |

|

Shu |

0.084 |

|

Duan of Xianbei |

0.081 |

|

Later Liang |

0.078 |

|

Southern Yan |

0.078 |

|

Shilla |

0.076 |

|

Funan |

0.064 |

|

Western-southern Yi |

0.062 |

|

Yutian |

0.062 |

|

Shanshan |

0.06 |

|

Sushen |

0.059 |

|

Former Zhao |

0.053 |

|

Western Regions |

0.048 |

|

Eastern Yi |

0.047 |

|

Xia |

0.043 |

|

Dayuan |

0.043 |

|

Western Yan |

0.034 |

|

Wa |

0.032 |

|

Jushi qianbu |

0.03 |

|

Haidong |

0.03 |

|

Tuyuhun |

0.029 |

|

Northern Yan |

0.026 |

|

Yuwen of Xianbei |

0.025 |

|

Yanqi |

0.02 |

|

Yanqi qianbu |

0.017 |

|

Kangju |

0.015 |

|

Tianzhu |

0.015 |

|

Xilu |

0.015 |

|

Rouran |

0.013 |

|

Dingling |

0.012 |

|

Gaochang |

0.012 |

|

Yilou |

0.012 |

Table 3

Matrix of Song and Northern Wei period negotiation data

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

27 |

28 |

|

1

|

0 |

33 |

4 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

1 |

14 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

|

2

|

28 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

3

|

20 |

27 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

4

|

9 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

5

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

6

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

7

|

8 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

8

|

9 |

15 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

9

|

20 |

15 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

10

|

0 |

14 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

11

|

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

12

|

0 |

18 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

13

|

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

14

|

16 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

15

|

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

16

|

0 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

17

|

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

18

|

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

19

|

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

20

|

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

21

|

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

22

|

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

23

|

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

24

|

8 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

25

|

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

26

|

6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

27

|

12 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

28

|

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Table 4

Centrality analysis results of Song and Northern Wei period negotiation data

|

Out-degree |

|

Song

|

2.815 |

|

Koguryŏ

|

1.815 |

|

Northern Wei

|

1.481 |

|

Tuyuhun

|

1.296 |

|

Rouran

|

0.889 |

|

Wudu

|

0.704 |

|

Komokhai

|

0.667 |

|

Paekche

|

0.593 |

|

Khitan

|

0.519 |

|

Linyi

|

0.444 |

|

Wa

|

0.407 |

|

(Panhwang)

|

0.296 |

|

Yutian

|

0.259 |

|

Karitan

|

0.222 |

|

Shilla

|

0.185 |

|

Dangchang

|

0.111 |

|

Sri Lanka

|

0.111 |

|

Funan

|

0.111 |

|

Kucha

|

0.074 |

|

(Padal)

|

0.074 |

|

Tianzhu Kapila

|

0.074 |

|

Mulgil

|

0.037 |

|

Yada

|

0.037 |

|

Tianzhu (Somaryŏ)

|

0.037 |

|

Tianzhu Kantoli

|

0.037 |

|

Tianzhu (P’aryŏ)

|

0.037 |

|

(Karat’a)

|

0.037 |

|

Kaya

|

0 |

|

In-degree |

|

Song

|

5.63 |

|

Northern Wei

|

5.111 |

|

Tuyuhun

|

0.63 |

|

Wa

|

0.481 |

|

Koguryŏ

|

0.333 |

|

Wudu

|

0.296 |

|

Paekche

|

0.222 |

|

Shilla

|

0.185 |

|

Dangchang

|

0.148 |

|

Linyi

|

0.111 |

|

Rouran

|

0.074 |

|

(Panhwang)

|

0.037 |

|

Karitan

|

0.037 |

|

(Padal)

|

0.037 |

|

Mulgil

|

0.037 |

|

Komokhai

|

0 |

|

Khitan

|

0 |

|

Yutian

|

0 |

|

Sri Lanka

|

0 |

|

Funan

|

0 |

|

Kucha

|

0 |

|

Tianzhu Kapila

|

0 |

|

Yada

|

0 |

|

Tianzhu (Somaryŏ)

|

0 |

|

Tianzhu Kantoli

|

0 |

|

Tianzhu (P’aryŏ)

|

0 |

|

(Karat’a)

|

0 |

|

Kaya

|

0 |

Table 5

Negotiation route data matrix of Song and neighboring countries 42

|

Song |

Kogurŏ |

Paekche |

Mahan |

Shilla |

Kaya |

Wa |

Linyi |

|

Song

|

0 |

2 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

Kogurŏ

|

3 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

Paekche

|

3 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Mahan

|

0 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

|

Shilla

|

0 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

Kaya

|

0 |

1 |

0 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

Wa

|

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

|

Linyi

|

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Funan

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

Bibliography

1. Seong-jin Ahn. "Tojarŭl t’onghae pon 4segi ch’o paekchewa tongjinŭi kyoryu [Exchanges between Baekje and Eastern Jin during the early 4th Century as viewed through Porcelains]." Han’guksahakpo (The Journal for the Studies of Korean History) 42 (2011).

2. Collar Anna, Coward Fiona, Brughmans Tom, Mills Barbara J. "Networks in Archaeology-Phenomena, Abstraction, Representation." Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 22-1 (2015).   3. Kil-nam Baek. "4segi mal~5segi ch’oyŏp ‘paekchewang’oŭi ch’aekpong paegyŏnggwa ‘todokpaekchejegunsa’oŭi ŭiŭi [How the Entitlement of ‘Baekje King (百濟王)’ came about in the late 4th, early 5th century, and the meaning of the title ‘Dodok Baekje Jegunsa (都督百濟諸軍事, Supreme Commander of the Baekje Troops)’]." Yŏksawa hyŏnshil(Quarterly review of Korean history) 115 (2020).

4. Knappett Carl. "Introduction: why networks? Network Analysis in Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.  5. Rollinger Christian. "Prolegomena. Problems and Perspectives of Historical Network Research and Ancient History." Journal of Historical Network Research 4 (2020).

6. Cline Dane Harris. "Athens as a Small World." Journal of Historical Network Research 4 (2020).

7. Graham . "Networks, agent-based models and the Antonine itineraries." Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 19-1 (2006).   8. Jina Heo, Wongeun Song. "Chŏngch’igyŏngjejŏk kwanjŏmesŏ pon 5-6segi yŏngsan’gang kobunsahoeŭi kusŭl kyoyŏkt’psyut’ongt’psobi [Trade, Distribution, and Consumption in the Yeongsan River Tomb Society in the 5th and 6th centuries from a Political Economic Perspective]." Hanguk Kogo-Hakbo(The Journal of Korean Archaeology) 123 (2022).

9. Eunkyung Hong. "Han’guk shinsŏkkishidae sahoegwan’gyemangbunsŏk (SNA)ŭl wihan yebigŏmt’o [A Preliminary Study on the Social Network Analysis (SNA) of the Korean Neolithic period]." Kogohak (Journal of the Jungbu Archaeological Society) 18-3 (2019).

10. Senghyun Hong. "Wijinnambukchoshigi chunghwaŭishigŭi pyŏnyonggwa tongashia kukchejilsŏ [The Transformation of Sinocentrism in the Wei, Jin, Nan, and Bei (魏晉南北朝) Period and the Regional Dynamics of East Asia]." Dongbuga Yeoksa Nonchong(The Journal of North-East Asian history) 40 (2013).

11. Soo Hur. "ŏhwi yŏn’gyŏlmangŭl t’onghae pon chegugŭi ŭimi -chegukchuŭiwa chegukŭl chungshimŭro- [The Meaning of “Jegook (帝國)” in Corpus Networks -Centering on the analysis of “Imperialism” and “Empire”-]." Taedongmunhwayŏn’gu (Journal of Eastern studies) 87 (2014).

12. Soo Hur. "Kaebyŏk nonjoŭi sahoejuŭihwae kwanhan saeroun chŏpkŭn -t’op’ik yŏn’gyŏlmang punsŏkŭl chungshimŭro- [A New Approach to Socialization in Gaebyeok’s Tone: Focusing on Topic Network Analysis]." Inmunnonch’ong (Seoul National University the Journal of Humanites) 78-1 (2021).

13. hwa Jeong Sun. "SNS kirokŭl t’onghae pon taejungŭi kaya inshik - t’eksŭt’ŭ net’ŭwŏk’ŭ punsŏkŭl chungshimŭro [The Public’s Perception of Gaya through SNS Records: Focusing on Text Network Analysis]." Dongbuga Yeoksa Nonchong(The Journal of North-East Asian history) 78 (2022).

14. hwa Jeong Sun. "Chunggodŭnghakkyo yŏksagyogwasŏŭi kayasa inshikkwa imijit’elling – t’eksŭt’ŭ net’ŭwŏk’ŭ punsŏkŭl chungshimŭro –”. Y [Awareness and Image-Telling of Gaya History in Middle and High School History Textbooks – Focusing on Text Network Analysis -]." ŏksagyoyuk (The Korean History Education Review) 164 (2022).

15. Turner Jonathan. "Net’ŭwŏk’ŭ punsŏk [Chapter 27 Network analysis]." Hyŏndae sahoehak iron. [Contemporary sociological theory].

Yoon-tae Kim

. Seoul: Nanam, 2019.

16. Dongseok Kang. "Chisŏngmyosahoeŭi net’ŭwŏk’ŭ kujowa sŏnggyŏk kŏmt’o [A Study on the Network Structure and Characteristics of Dolmen Society]." Hanguk Sanggosa Hakbo(The Journal for Korean archaic history) 105 (2019).

17. Kee-young Kwahk. Sosyŏllet’ŭwŏk’ŭbunsŏk. [Social network analysis]. Seoul: Ch’ŏngnam, 2017.

18. Jongil Kim. "Myŏn, chŏm, sŏn kŭrigo yŏn’gyŏlmang [Surface, Point, Line and Network]." Inmunnonch’ong (Seoul National University the Journal of Humanites) 79-1 (2022).

19. Jong-wan Kim. Chunggungnambukchosayŏn’gu – chogong kyobinggwan’gyerŭl chungshimŭro. [A Study on the Chinese World Order of the Southern-and-Northern Dynasties Period]. Seoul: Ilchokak, 1995.

20. Yong-Hak Kim. "Sahoeyŏn’gyŏlmang punsŏgŭi kich’ogaenyŏm-kujojŏk kwŏllyŏkkwa yŏn’gyŏlmang chungshimsŏngŭl chungshimŭro [Structural Power and Network Centrality in Social Network Analysis]." The Journal of the Humanities 58 (1987).

21. Yong-Hak Kim. Sahoe yŏn’gyŏlmang iron. [Theory of social network]. Seoul: Pakyoungsa, 2004, (revised edition).

22. Yong-Hak Kim. Sahoe yŏn’gyŏlmang punsŏk. [Social network analysis]. Seoul: Pakyoungsa, 2016, 4th edition.

23. Ilhong Ko. "Puk’anŭi parhae yŏn’gusa sŏsurŭl wihan saeroun chŏpkŭn-puk’an haksulchi mongnok’wa saŏp kyŏlgwamurŭl hwaryonghan naeyongbunsŏk [Content Analysis of North Korean Research Journal Data: a New Way of Writing Histories on Balhae Research Undertaken in North Korea]." Inmunnonch’ong (Seoul National University the Journal of Humanites) 77-4 (2020).

24. Ilhong Ko. "Kogohak charyoŭi net’ŭwŏk’ŭ punsŏkŭl t’onghan oeraeyumul yut’ongmang kŏmt’o: yŏngnamjiyŏk mudŏm ch’ult’o osujŏnŭi haesŏkŭl wihan yungbok’apchŏk shido [Network Analysis of Foreign Object Circulation in Ancient Korea: Wushu Coins from Yeongnam Burials]." Asia Review 11-1 (2021).

25. Ilhong Ko. "Net’ŭwŏk’ŭ shigak’wawa kogohak charyoŭi hwaryong - nangnanggobunŭi saryerŭl chungshimŭro [Network Visualization and the Utilization of Archaeological Data the Example of Nangnang (Lelang) Tombs]." Inmunnonch’ong (Seoul National University the Journal of Humanites) 79-1 (2022).

26. Byungdo Lee. "Kŭnch’ogowangt’akkyŏnggo [A study on the territorial expansion of the King Kŭnch’ogo]." Han’gukkodaesayŏn’gu. [A Study of Ancient Korean History]. Seoul: Pakyoungsa, 1976.

27. Sangkuk Lee. "Pikteit’ŏ punsŏk kiban han’guksa yŏn’guŭi hyŏnhwanggwa kanŭngsŏng tijit’ŏl yŏksahagŭi shijak [Conditions and potentials of Korean history research based on ‘big data’ analysis: the beginning of ‘digital history’]." Ŭngyongt’onggyeyŏn’gu (The Korean Journal of Applied Statistics) 29-6 (2016).

28. Sangkuk Lee. "Han’guksa yŏn’guwa tijit’ŏryŏksahak yŏn’gubangbŏmnon ?yangjŏkpunsŏkŭl chungshimŭro- [A Method for Research in Korean History -Focusing on a Quantitative Analysis of Digital History-]." Han’guksayŏn’gu(The Journal of Korean History) 197 (2022).

29. Soo-sang Lee. Net’ŭwŏk’ŭ punsŏk pangbŏmnon. [Network analysis methods]. Seoul: Nonhyŏng, 2012.

30. Soo-sang Lee. Net’ŭwŏk’ŭ punsŏkpangbŏbŭi hwaryonggwa han’gye. [Network analysis methods applications and limitations]. Seoul: Ch’ŏngnam, 2018.

31. Isaksen Leif. "The application of network analysis to ancient transport geography-A case study of Roman Baetica." Digital Medievalist 4 (2008).  32. Dong-min Lim. "Advanced Technology of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and Korean Ancient History – Study on the use of artificial intelligence to decipher wooden tablets and the restoration of ancient historical remains using virtual reality and augmented reality-." International Journal of Korean History 24, no. 2 (2019).

33. Dong-min Lim. "Paekche hansŏnggi haeyang net’ŭwŏk’ŭ yŏn’gu [The study on the marine network of the Hansŏng period of Paekche]." Doctoral dissertation of Korean history department Korea University, 2022.

34. Dong-min Lim. "Net’ŭwŏk’ŭ punsŏkkwa han’guk kodaesa yŏn’guŭi chŏmmok kanŭngsŏng - haman sŏngsansansŏng mokkanŭl chungshimŭro – [Applicability of Network Analysis in Ancient Korean History Studies -Focusing on the Sŏngsan Fortress Wooden Tablets-]." Han’guksayŏn’gu(The Journal of Korean History) 197 (2022).

35. Han-je Park. Chunggukchungsehohanch’ejeyŏn’gu. [The study on the Sino-Barbarian Synthesis in medieval China]. Seoul: Ilchokak, 1988.

36. Junyoung Park. "Yŏksa kogohak yŏn’gurŭl wihan net’ŭwŏk’ŭ punsŏk pangbŏmnonŭi hwaryong kanŭngsŏng -kodae yŏngsan’gangyuyŏkkwa kaya kwŏnyŏk ch’ult’o kusŭl charyorŭl chungshimŭro [The Applicable Potential of Using Network Analysis Methods for Historical and Archaeological Research Focusing on Ancient Beads Excavated from the Yeongsan River Basin and Gaya Region]." Inmunnonch’ong (Seoul National University the Journal of Humanites) 79, no. 1 (2022).

37. Peeples Matthew A. "Finding a place for Networks in Archeology." Journal of Archaeological Research 27-4 (2019).

38. Giovanni Ruffini. Social Networks in Byzantine Egypt. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

39. Ho-joon Seo. "Pikteit’ŏwa han’guk kodaesa yŏn’gugyŏnghyang [Big Data and Research Trends of Korean Ancient History]." DAEGU SAHAK (The Journal of History in Daegu) 144 (2021).

40. Young-soo Seo. "Samgukkwa nambukcho kyosŏbŭi sŏnggyŏk [The historical nature of negotiation during the Three Kingdoms with The Northern and Southern dynasties]." Dong Yang Hak(The Oriental Studies) 11 (1981).

41. Kyong Shin Eun. "The Morphology of Resistance Korean Resistance Networks 1895–1945." Sahoegwahakyŏn’gu (Journal of Social Science) 61, no. 2 (2022).

42. Ho-kyu Yeo. "4segi tongashia kukchejilsŏwa koguryŏ taeoejŏngch’aegŭi pyŏnhwa-taejŏnyŏn’gwan’gyerŭl chungshimŭro- Changes in the East Asian International Order and in the Foreign Policy of Kogury in the 4th

[Century]." Yŏksawa hyŏnshil(Quarterly review of Korean history) 36 (2000).

43. Ho-kyu Yeo. "4segi-5segi ch’oyŏp paekcheŭi taejunggyosŏp yangsang [Paekche’s negotiations with China in the 4th and early 5th centuries]." Paekcheŭi sŏngjanggwa chungguk. [The growth of Baekje and China]. Seoul: Baekje Museum, 2015.

44. Misaki Yoshiaki.

Ohoshibyukkuk – chungguksasangŭi minjoktaeidong

. [The Great Migration of Peoples in the History of The Sixteen Kingdoms].

Young-hwan Kim

. Seoul: Kyung-in publishing company, 2007.

Appendices

Annex Table 1

The matrix of negotiation data in the Eastern Jin and Sixteen Kingdoms

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

27 |

28 |

29 |

30 |

31 |

32 |

33 |

34 |

35 |

36 |

37 |

38 |

39 |

40 |

41 |

42 |

43 |

44 |

45 |

46 |

47 |

48 |

49 |

50 |

51 |

total |

|

1

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

8 |

13 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

40

|

|

2

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1

|

|

3

|

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

18

|

|

4

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1

|

|

5

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

12

|

|

6

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

4

|

|

7

|

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |