모호한 전환점: 1260년 전후의 고려-몽골 관계

국문초록

1259년 몽골을 방문했던 고려 왕전(王倎) 사절단은 화북(華北)지역을 지나갔을 때 친 쿠빌라이 세력, 특히 그중의 유학자들과 긴밀하게 접촉했기 때문에 그 이후 정치적 혼란 속에서 쿠빌라이를 지지했다. 쿠빌라이 측근 유학자를 매개로 1260년 고려 왕희 (王僖) 사절단은 쿠빌리이 정권으로부터 “출륙”(出陸)의 연기를 받아내는 데 성공하였다. 1260년 쿠빌라이 정권은 한 조서에서 한자 “藩”으로 고려를 지칭하고 조공 체계의 문화배경 속에서 고려의 지위를 확정하였다. 그러나 쿠빌라이 본인은 여전히 몽골 전통에 따라 고려의 역할을 설정하였다. 고려 사절단과 몽골 정권의 유학자들은 정치개념의 애매모호함을 활용해서 조공체제의 요소를 여몽관계에 주입시키면서 몽골제국의 외교전통을 크게 전환시켰다.

주제어: 김구, 유신(儒臣), 조공체제, 육사(六事)

Abstract

A Koryô mission led by Wang Chôn visited the Mongol in 1259 and had intense contacts with pro-Qubilai forces. Especially the Confucian scholars in North China, and therefore turned to Qubilai in the political turmoil. With the mediation of the scholar-ministers in Qubilai’s court, another Koryô mission led by Wang Hûi in 1260 succeeded in seeking an allowance for postponement of the Koryô court’s return to the mainland (出陸). An edict composed by some scholar-minister of the Mongols in 1260 used the word fan (藩) to refer to the Koryô and defined it as a vassal under the tributary system. But Qubilai himself still regarded the Koryô as submitted following the tradition of the Mongols. Under a kind of ambiguity, the Koryô missions and the scholar-ministers of the Mongol together had brought new elements into the Koryô-Mongol relationship and altered the mongol tradition.

KeyWords: Kim Ku, scholar-ministers, tributary system, six obligations

Introduction

The rise and expansion of the Mongol empire in the first half of the thirteenth century 1 created a serious crisis in the tributary (冊封-朝貢) system, which had been providing a feasible framework for five hundred years for exchange between the mainland regimes like the Tang, Song, Khitan Liao and Jurchen Jin, and those on the Korean Peninsula including the Silla and Koryô, which allowed the latter de facto independence while ritually recognizing the suzerainty of the former. 2

Despite the Koryô’s efforts for continuing the tributary system, the Mongols, imposing its own policies on the newly subjected countries,kept requiring the Koryô to fulfill a set of demands, or the “Six Obiligations” (六事). 3 This confrontation led to more than forty years of war until the enthronement of Qubilai in 1260, the fifth Qahan of the Mongol empire, when the terms, symbols, ideas and other elements of the tributary system were reintroduced into the relations between the Mongols and Koryô, and therefore the tenor of the bilateral relationship changed from war to diplomacy. 4

How could this transition have happened? So far, historians have attributed this to Qubilai’s personal preference to Han(漢)-Chinese culture and/or his private friendship with the Koryô king Wônjong (元宗). 5 However, this explanation cannot answer the following questions: How and why did Qubilai accept ideas that were completely alien to his native nomadic tradition? And why were the Mongol’s policies toward the Koryô highly unstable and inconsistent during and after the 1260s? 6 Was Qubilai’s preference or character really so changeable? I would propose that a methodological change is in need. Present narratives of this transition have been based on the records of official histories including the Yuan Shi (元史)and the KoryôSa (高麗史), especially the annals (本紀/世家) that as a genre tend to bring about images of emperors or kings as omnipotent. Thus, a de-Qubilai-centered analysis is necessary here, which further requires us to pay more attention to sources other than official histories.

It’s commonly known that Qubilai was the first Mongol Qahan to recruit Confucian scholars on a large scale from North China for his think tank. 7 They had extensively influenced many aspects of policy in the early period of Qubilai’s reign. 8 But scarce attention has been paid to how they were involved in Mongol-Koryô interactions. A letter written by a Koryô minister Kim Ku (金坵) has connected Koryô with this political group in Qubilai’s court, thus providing us with a new standpoint for observing the transition mentioned above. Thus, we begin our discussions from this letter and see how they interacted and shaped the history of Northeast Asia around 1260.

Kim Ku and the Letter to Scholar Zhang

Kim Ku (1211–1278) was born in Puryông (扶寧) county and started his political career at the age of twenty-two by passing the civil service examination. In 1240, he travelled as a member of a Koryô mission to visit the Mongols. During the Koryô king Wônjong’s reign, Kim Ku served as the Affair Managing Vice-director of the Secretariat (中書侍郎平章事) until his retirement. Because of his political experience and great talent for writing in Chinese, Kim Ku had been in charge of composing diplomatic documents, 9 including the Letter to Scholar Zhang (hereafter the Letter) discussed here. 10

The Letter was written on behalf of the Koryô king Wônjong (元宗), named Wang Chôn (王倎). Leaving out the greeting words at the beginning, the texts could be divided into three parts. The first part commends the merits and achievements of the addressee Scholar Zhang, comparing him with the noted Confucian scholar Shusun Tong (叔孫通), who had established the court etiquette for the emperor Gaozu (高祖) of the newly founded Han dynasty in 200 BC. The second part of the Letter appreciates Scholar Zhang for his help during Wang Chôn’s “audience with the emperor (親朝)” in North China, and his contributions to the Mongol’s cherishing policies toward the Koryô after Wang Chôn’s “return to his own country (還國)”.

This indicates that Scholar Zhang was undoubtedly a Chinese Confucian scholar who was very close to Qubilai and to the center of power in the Mongol empire. In extant sources, two of Qubilai’s scholar-ministers could fit the descriptions, namely Zhang Yi (張易) and Zhang Wenqian (張文謙), both of whom served as secretaries ( bicigci in Mongolian) for Qubilai before his enthronement. Zhang Yi was appointed the Executive Official Participant of the Secretariat (參知政事) when the new Qahan ascended the throne in 1260, 11 and Zhang Wenqian the Left Executive Assistant of the Secretariat (中書左丞). 12 Evidence suggests that Zhang Wenqian had been dispatched for some military task, thus had no chance to meet Wang Chôn during his sojourn in North China. 13 So, Zhang Yi was more likely to be Scholar Zhang. In fact, he had an even higher status in Qubilai’s court. 14

The third part is the main concern of this letter and it says,

“People of the Samhan (三韓) are extremely grateful, hoping for a new life. Following the edicts [from Qubilai], they have started moving back to the old capital and building houses. But the old capital has been abandoned for nearly thirty years. Trees and weeds have to be removed before new palaces and houses can be constructed. This takes time, so it’s still desolate there. How will the [Mongol] envoys report after seeing this? It is very worrying. We hope your Excellency will understand the true situation, grant us your compassion, and thus enable our little state to serve [the great] forever.” 15

Facing the intrusions of the Mongol troops, the Koryô court together with the people in the old capital Kaegyông (開京) all moved onto the Kanghwa (江華) island off the eastern coast of the peninsula in 1232. For the next forty years, the Mongols kept requiring the Koryô court to move back. This was the so called “return-to-mainland (出陸)” issue. 16

Although evidence indicates that Wang Chôn had promised returning to the mainland before his return from North China, 17 he certainly would not like to do it at that point. Onthe twenty-ninth day of the fourth lunar month of 1260, Wang Chôn sent another mission led by the Duke Yôngan (永安公) named Wang Hûi (王僖) whose ritual task was to attend a ceremony for Qubilai’s enthronement, while the real task was to seek the Mongol’s allowance for postponement of return-to-the-mainland. It was precisely for the latter purpose that the Letter, together with a petition to Qubilai, had been carried by Wang Hûi to Kaiping (開平), the vice-capital of the Yuan dynasty. 18 It’s quite clear that Wang Chôn believed Scholar Zhang to be the one willing and capable to lend a hand based on his experience with this person before. Therefore, we should firstly have a look at Wang Chôn’s journey to North China.

Wang Chôn’s Journey to North China

To have an audience with Qahan was one of the Mongol’s conventional requirements of the leaders of all the newly subjected forces or states. The Koryô had declined this for many years, but after a coup in 1258 successfully toppled the military clan of Ch'oe (崔氏), which was the real controller of the state for more than half a century and was obstinately hostile to the Mongols, 19 the “crown prince (世子)” named Wang Chôn was finally sent to the Mongols to seek peace. 20

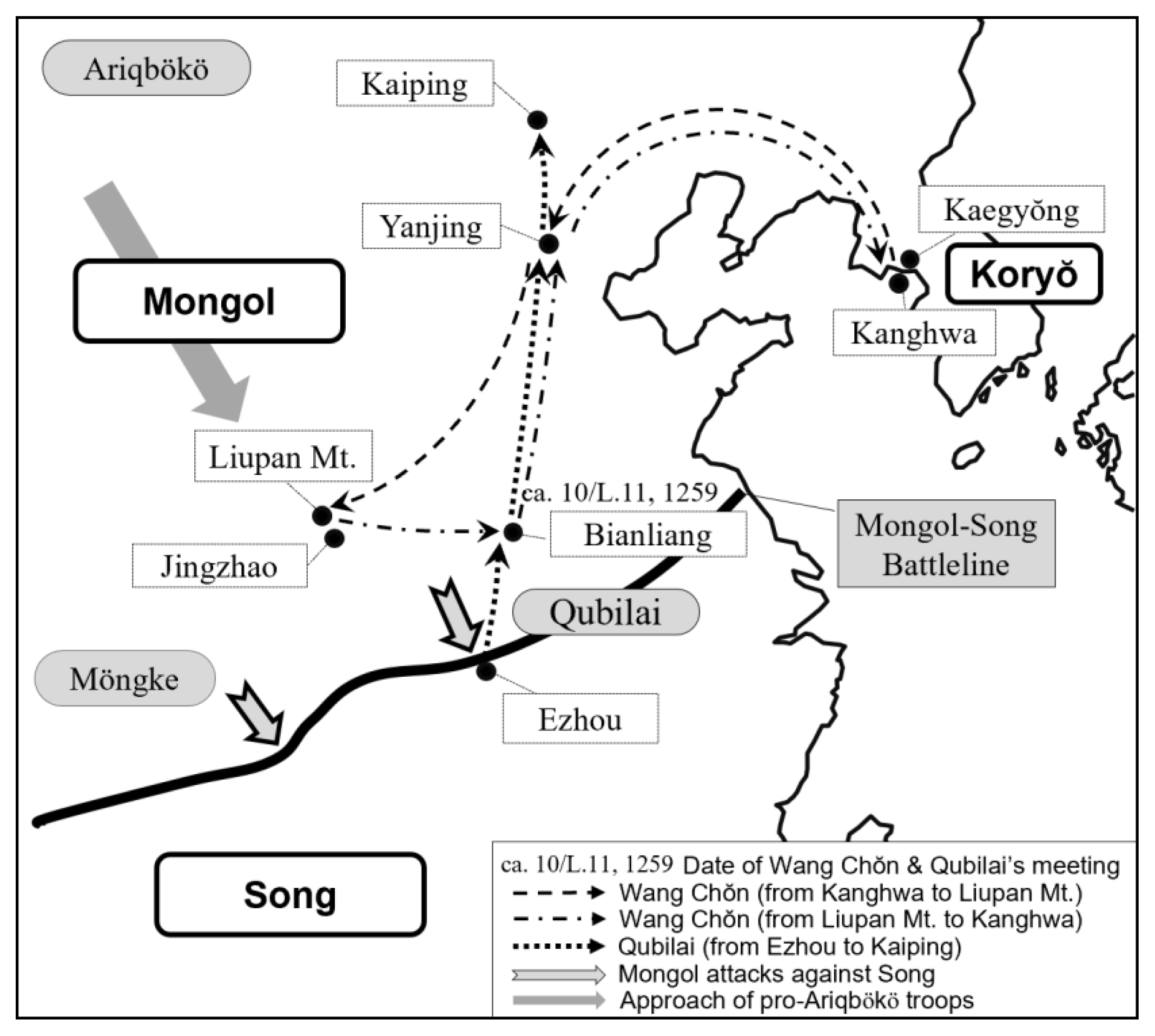

The mission set out in the fourth lunar month of 1259, went by way of Yanjing (燕京) and Tongguan (潼關) toward today’s Sichuan province in Southwest China where Möngke Qahan was commanding a massive attack on the Southern Song ( Map 1). When they had just arrived at the Liupan Mountain (六盤山), Möngke died at the battlefront. His two younger brothers, Qubilai and Ariqbökö, both started mobilizing troops and fighting over the throne. Liupan had soon fallen into control of pro-Ariqbökö forces. However, the Koryô mission made an extraordinary decision. They moved eastwards, met with Qubilai at Bianliang (汴梁), a midway city of Qubilai’s northward march from the Mongol-Song battlefield near Ezhou (鄂州), and followed him to Yanjing. At that point, the Koryô king Kojong (高宗)’s death was heard. Wang Chôn was then escorted back by the Mongol troops and assumed the throne. One of the key reasons that the Koryô mission turned to Qubilai so quickly and firmly was their contacts with pro-Qubilai forces, especially the Confucian scholars in North China. In Yanjing, one of the core scholar-staffs of Qubilai named Hao Jing (郝經) wrote down his observations on the mission:

“(They) walked through the market (of slaves from the Koryô), all covering their faces and crying; the cries, so loud and miserable, pierced the ears of the Yenjing people.” 21

In Jingzhao (京兆), Wang Chôn was invited by a “land governor (守土者)” to bathe in a hot spring at the Huaqing Palace (華清宮). But Wang Chôn said it had been the bathing spot of the Emperor Ming (明皇) of the Tang dynasty and as a prince of a vassal state he could not cross over. Therefore, he was admired as “knowing the rites (知禮).” 22 The land governor here was no doubt pro-Qubilai because Jingzhao had been bestowed to Qubilai since 1253 as part of his share ( qubi) of the Mongol empire. And the audience who could understand the reference to the Emperor Ming and comment to others about “knowing rites” surely had an educational background in Confucianism. During Möngke’s reign, the Liupan Mountain was an important base for the Mongol’s military actions in Southwest China. Qubilai had stayed here for about three years in all before and after his conquering Dali (大理) in 1253. 23 Consequently, pro-Qubilai forces existed in this area. Yelü Zhu (耶律鑄), a prominent scholar-minister in the Mongol court, abandoned his wives and sons and escaped from Liupan to Qubilai upon arrival of the pro-Ariqbökö troops. 24 The Koryô mission was also among those promptly evacuating Liupan. Wang Chôn had not stayed with Qubilai for a very long time. Extant records on the relevant dates are somewhat confusing, 25 so some discussion is necessary here. Qubilai set out from the battlefront at Ezhou on the second day of the leap eleventh lunar month of 1259 and arrived at Yanjing on the twentieth day of the same month. 26 According to the distance, his first meeting with Wang Chôn at Bianliang must have occured at some time around the tenth day of that month. On the other side, Wang Chôn arrived at Kaegyông on the seventeenth day of the third lunar month of 1260, and Kanghwa three days later. Before that, he had stayed at Sôgyông (西京) for eight or nine days. 27 If these records are reliable, Wang Chôn had to leave Yanjing no later than the beginning of the second lunar month of 1260. 28 So the total duration for him accompanying Qubilai was about three months, namely from the middle of the leap eleventh lunar month of 1259 to the beginning of the second lunar month of 1260. Three months were not long enough for establishing any true friendship between Wang Chôn and Qubilai, especially when the two could not even communicate directly. Fortunately, the Mongol empire at that point was undergoing fundamental changes. After more than fifty years of war and slaughter, the Confucian scholars in North China had finally found a potential Mongol ruler willing to learn and adopt some Confucian ideologies and practices. Most of the scholar-ministers in Qubilai’s court shared a political agenda of “acquiring the emperor and going the way (得君行道),” which means to educate the ruler with Confucianism, and enthrone him, thus creating a world of peace. 29 Now Qubilai was prevailing in the contest for the throne and things could nott be more encouraging. Certainly, Wang Chôn had a sense of this political atmosphere, so the Letter says that, “[now is] the moment that occurs only once in a thousand years for ceasing war and cultivating civilization.” 30

In fact, Qubilai at first didn’t realize the value of Wang Chôn. But one of his scholar-staffs named Zhao Liangbi (趙良弼) suggested the following:

“[The crown prince of Koryô] has stayed here for two years. The treatment is not good enough to cherish his heart. Once going back, he will never come again. [We] could provide him with a good house and food, and treat him like a real vassal king. His father is said to be dead. If we invest him with the kingship [of Koryô] and escort him back, he must be grateful and willing to perform the duties of a vassal. This is to acquire a state without using any soldiers.” 31

Another scholar-staff named Lian Xixian (廉希憲) had made a similar suggestion. 32 The Letter tells that Scholar Zhang also made contributions on this issue, so Qubilai promptly, “resettled (Wang Chôn) in splendid houses and comforted (him) with elegant music.” 33 Besides, the Letter says that Scholar Zhang, “exhaustively reported our situations and facts [to Qubilai],” 34 which indicates that it was the scholar-ministers who had mediated the communication between the Koryô mission and Qubilai. The Letter further tells that it was Scholar Zhang’s protection that “suppressed all slanderous words.” 35 Two cases of “slanderous words” are recorded in the KoryôSa. In Yanjing,a son of a former high official of Koryô named Hong Pogwôn (洪福源) who had defected to the Mongols about forty years before accused the Koryô in 1259 of cheating the Qahan. 36 Later in the first lunar month of 1260 another Koryô official defected to the Mongols and again accused Koryô of the same offence. 37 Besides, in Qubilai’s court there were still opinions insisting on military conquest. It was the scholar-ministers including Scholar Zhang who had refuted those accusations and opinions before the Qahan. Therefore, Wang Chôn’s being escorted back should be understood as a policy proposed by the scholar-ministers rather than any personal preference of Qubilai himself. 38 In an important memorial, Hao Jing once advised Qubilai that, “peace of civilization (文致太平)” not only was good for the people and state but also could “unify all under heaven (天下可一).” 39 To acquire Koryô by investing Wang Chôn was exactly an application of this theory.

The Wang Hûi mission and the return-to-mainland issue

The Koryô court expecting to continue at least semi-independence insisted on withdrawal of Mongol troops as a precondition for returning-to-the-mainland, 40 even after the power of the Ch'oe clan was overturned. In the twelfth lunar month of 1258, a small mission led by Pak Hûisil ((朴希實) was sent to the Mongols to notify them of the death of Ch'oe Ûi and the coming visit of Wang Chôn and also to petition to Möngke that, “although we would like to obey the Great’s orders, the troops of heaven (天兵) are suppressing the land, so we dare not move out, like a mouse in the hole watched by a cat outside.” 41 But Möngke’s reply revealed his uncompromising stance for having a military stationed on the peninsula and for full submission of Koryô.

If you are truly on our side, why are you afraid of our troops? Moreover, the land to the north of Sôgyông had been garrisoned by our troops before. If you move out of the island quickly, I will at the most order them not to intrude. The crown prince can go back with you if he is still in your territory. Let him come to me alone if he is already on our land. 42

For Möngke, it was a matter of course that the Mongol troops should garrison in Koryô. Otherwise, the visit of the crown prince would be of no use and thus unnecessary. The military arrangement had not been agreed upon yet, so to move out of Kanghwa island or not would still be a secondary issue.

However, things changed after Wang Chôn’s assumption of the throne. For whatever reason, two new edicts from the Mongols made big concessions declaring that (1) the Koryô could have its territory restored, provided it promised to “be an eastern fan (藩, vassal, literally fence) forever”; (2) the Mongol troops would be gathered and later withdrawn; (3) all the anti-Mongol forces in Koryô would be amnestied; and (4) all the Koryô captives would be released. 43 These policies were indeed much more friendly compared to those under previous Qahans and thus ended the military tension, at least ostensibly, which immediately brought the return-to-mainland issue to the top of the political agenda. Both sides understood that the stationing of the Koryô court on Kanghwa island was not only a result of pressure but also a symbol of hostility and resistance. In response to the accusation from the Mongols of “unyielding (未臣服)”, Koryô said that they always served the Mongols and “nothing seems violating but that we, fearing the might of the Great, moved onto this island some days ago.” 44 An edict delivered in the fourth lunar month of 1260 from the Mongols euphemistically urged that “[return-to-mainland] is what I am glad to see. Now is the time for cultivation. Do not delay or miss the start of a year’s work.” 45 At the same time, Saridai (束里大), the general commander in charge of escorting Wang Chôn back, was still on Kanghwa island and kept urging and threatening him. At least three relevant conversations in 1260 are recorded in the KoryôSa.

“(On the twenty-eighth day of the third lunar month, Saridai met Wang Chôn and said:) ‘I really appreciate your hospitality. But it is not for eating and drinking on this island that King Qubilai has sent me. What will you do?’ The king had nothing to reply.” 46

“(On the fourteenth day of the sixth lunar month, Saridai met a Koryô official named Kim Pojông 金寶鼎 and said:)‘On the eve of your king’s return, he told the Qahan that he would move back to Songgyông (= Kaegyông) upon arriving at Kanghwa island. Now several months have passed, why has he not done anything? How many heads do you have? I have only one, so I’m very worried. There is nothing I can do here. I am returning.’ Bojeong had nothing to reply.” 47

“(On the eighth day of eighth lunar month, Saridai delivered what he claimed to be an oral instruction from Qubilai:) ‘Those who sit on the island, it is your decision! Those choosing to sit there, it is your decision! Is the king happy with this? Are the ministers and generals happy with this?’” 48

Under this pressure, the Koryô on one side divided all its court officials into three groups to station at Kaegyông by turns, pretending to be preparing for return-to-the-mainland. 49 On the other side, it tried to seize the opportunity of the Wang Hûi mission to seek for a diplomatic settlement on this issue. The Wang Hûi mission set out on the twenty-ninth day of the fourth lunar month of 1260, arrived at Kaiping in the sixth lunar month, and returned to Kanghwa on the seventeenth day of the eighth lunar month. 50 It brought back three edicts from the Mongols. Two of them mainly concerned ritual issues and thus are not crucial. The third one was the real achievement of this mission and it says,

“Dress of the Koryô will follow its tradition and shall not be changed. Only envoys from the Qahan will be sent, others shall be banned. When to return to the old capital is up to your own considerations. The troops will be withdrawn not later than the next autumn. The daruqaci Bolaqdai Ba'atur and others shall all be ordered to return. ...I universally cherish all under heaven, and sincerely do things. Please appreciate my heart, and do not hesitate and fear.” 51

It formally allowed the Koryô to postpone return-to-the-mainland, and moreover, specified many other cherishing policies that had not been proposed before. Nine days later, the aggressive Mongol general Saridai departed westwards. 52

From this point the new Koryô-Mongol relationship established a firm foothold. The Koryô did have expectations for this Wang Hûi mission, just as shown byt he humble letter to the Scholar Zhang requesting his help. Then, what had happened during Wang Hûi’s stay with the Mongols?

Scholar-ministers and Koryô-Mongol negotiations

The KoryôSa tells us that in Kaiping, Wang Hûi attended first a banquet hosted by the Central Secretariat (中書省) of the Mongols, then another banquet hosted by Qubilai who at that time said to Wang Hûi that,

“your state has served the Great for forty years. Now there are deputies from more than eighty states attending this assembly, can you find any treated as favorably as yours?” 53

No more direct records can be found in extant sources. Fortunately, however, a clerk in the Central Secretariat named Wang Yun (王惲) had written in his work diary about other missions from Koryô in the next year, which allows us to explore how negotiations between Koryô and the Mongols were carried out in Qubilai’s court.

On the tenth day of the sixth lunar month of 1261, Wang Sim (王愖), the new crown prince of Koryô, arrived at Kaiping to celebrate Qubilai’s victory over Ariqbökö. The next day, following an order from Qubilai, a banquet was held at the Central Secretariat Office (都堂). Seven of the Mongol’s ministers were in attendance, among whom five were noted Chinese Confucian scholars, namely Wang Wentong (王文統), Zhang Yi (張易), Zhang Wenqian (張文謙), Yang Guo (楊果) and Yao Shu (姚樞). The other two were Shi Tianze (史天澤), a Chinese military commander, and Qurubuq (忽鲁不花), a Mongolian imperial guard (怯薛, kesig in Mongolian). During the banquet, they had “written talks (筆談) ” respectively with the Assistant Chancellor (参政) of Koryô named Yi Changyong (李藏用) on the numbers of Koryô troops and military commanders, crop harvests, the calendar system, civil service examinations and so on. On the twelfth day, “the ministers entered [the palace] to meet [Qubilai]. The Emperor heard that negotiations went very well, so sent [Wang Sim] back bestowing an edict and a jade belt.” 54

This record shows clearly that negotiations on specific issues were carried out between the Koryô mission and the ministers of the Mongols which consisted mainly of the Confucian scholar-ministers. 55 Qubilai would not negotiate with the mission in person, but obtained information through his ministers, especially the scholar-ministers. The elegant sentences with classical Chinese allusions in the bestowed edict were obviously written by some Confucian scholar as well. 56

In fact, there was another Koryô mission that arrived nearly three months earlier on the fifteenth day of the third lunar month of the same year. The reply edict for this mission was also composed by the leading scholar-minister Wang Wentong. And even some days before, a Koryô minister had sent a letter greeting the Central Secretariat of the Mongols. Wang Wentong had also intended to write a reply letter but had given up because of Wang Yun’s advice that private connections with ministers from foreign countries was inappropriate. 57 Despite incomplete information, Qubilai probably also followed the suggestions from his scholar-ministers such as Wang Wentong for dealing with this Koryô mission. Additionally, “the ministers (诸相)” were in charge of an inquiry into a dispute between Wang Sun (王淳) and one of the above mentioned Hong Pogwôn’s sons on the twenty-fifth day of the fourth lunar month of 1261. 58 Wang Sun was sent from Koryô to the Mongols as a hostage twenty years earlier and had married a Mongol princess. In 1258, his wife accused Hong Pogwôn of disrespecting her husband, so Möngke put Hong Pogwôn to death. In 1261, his son Hong Dagu (洪茶丘) appealed to Qubilai. 59 Wang Yun tells us that the scholar-ministers were appointed to conduct the inquiry. Based on these records, it’s most likely that the negotiation on the return-to-the-mainland issue in 1260 was also carried out between the Wang Hûi mission and the Mongol ministers at the banquet hosted by the Central Secretariat. The whole process must be very similar to that of the Wang Sim mission in 1261. Although Wang Hûi did attend a banquet hosted by Qubilai, it was impossible for him to negotiate with the Qahan directly. The mediation of the scholar-ministers in Qubilai’s court were indispensable to the success of the Wang Hûi mission.

Historians have already pointed out that the Mongol’s edict delivered by Jing Jie (荆节) on the ninth day of the fourth lunar month of 1260 (hereafter the Jingjie edict) was part of the corner stone for Koryô-Mongol relations in the next one hundred years. 60 However, a further analysis on its texts is still revealing and necessary here.

“My emperor Taizu established the foundation of the great empire, and holy and wise emperors succeeded one another. … All the affiliated states and marquises, granted with land inheritable for their off-spring and dispersed over the range of 10,000 li(里), are all former strong enemies. This seen, the principles of my forefathers are very clear without need to be expressed in words. … (I) escort the crown prince back restoring the old territory. … The ministers in power will not be misled by runaways, and the covenant will not be wrecked by slanderous words. … Upon arrival of this edict, those who once rebelled at home and resisted the emperor’s army, or revolted again after submission, … will all be given amnesty. The crown prince, please be dressed, be on carriage, return to your state and assume the throne. … My troops will not cross the border any more, for which the order has been issued and I will keep my words. Anyone who revolts and insubordinates will not just affect your king but also violate my codes, thus can be killed by anyone who follows the clear laws of mine. The Crown Prince, please be the king. Please respectfully follow my orders, be an eastern fan (藩, vassal) forever, and carry forward my instructions.” 61

Firstly, this edict claims that according to “the principles of my forefathers,” the Mongol empire had allowed many subjected vassals to be “granted with land inheritable for off-spring.” Indeed, leaders of submitted states, tribes or any other forces had always been granted titles of noyan of different ranks such as Tumen and Mingγan that were usually hereditary. However, these noyans were only administrative and military officials within the Mongol empire rather than monarchs of highly independent tributary vassals. They were directly subject to Qahans or other members of the Golden Lineage, 62 just as the common people under their administration. 63 In fact, the Mongol empire before Qubilai had never recognized any bilateral relationship under the tributary pattern, neither had it accepted the existence of any de facto tributary vassal. 64

Secondly, the word fan used to refer to Koryô at the end of this Jingjie edict is also ambiguous. In the Mongol-Yuan period, the character fan was used to refer mostly to other uluses (people, states) of the Golden Lineage apart from the ulus of Qahan. It occurs 149 times in all in the Yuan Shi which was compiled at the beginning of the Ming dynasty based on archives, biographies and other sources produced during the Mongol-Yuan period. Among them, 99 times refer to non-Qahan uluses of the Golden Lineage, and only 14 times refer to non-golden-lineage vassals. An often-used compound word Zong fan (宗藩, suzerain-vassal or vassal of suzerain) occurs 10 times in the Yuan Shi, all meaning non-Qahan uluses of the Golden Lineage. Koryô was actually the first non-golden-lineage vassal to be called a fan and the edict discussed here was exactly the first case. From the perspective of the tradition of the Mongols, to call Koryô a fan and promise it hereditary kingship and land was extremely abnormal. Although the edict claims to follow “the principles of my forefathers”, its real ideological basis was still the tributary system familiar to the scholar-ministers. 65

According to the KoryôSa, this edict was a response to the suspicion that some “unforeseen events (變故)” might have happened since Wang Chôn had lingered on at Sôgyông for quite a long time on his way back to Kanghwa island. 66 So, it on one side reaffirmed the promise of “restoring the old territory” and amnesty for all. On the other side it threatened that anyone violating “my codes” in the future would be destroyed without mercy. This was an endorsement for both Wang Chôn and the scholarministers supportive of gambling on Wang Chôn. Certainly, Qubilai would not compose this edict himself but appoint someone from his scholar-ministers instead. So again, this edict should be understood as an embodiment of policies elaborated by the scholar-ministers rather than Qubilai’s own preference. It’s very likely that Koryô had understood the hidden story behind this edict. So, while the petition to Qubilai flattered this Qahan as the “most benevolent (至仁),” 67 the Letter to Scholar Zhang disjunctively questioned that “would there be such edicts of great virtue of cherishing life without your excellency’s sincere facilitation and ingenious induction.” 68 In this context, it is not surprising that Wang Chôn would write a letter to Scholar Zhang requesting his assistance. Hao Jing, who had written a poem on the Wang Chôn mission at Yanjing in 1259,was sent for negotiation with the Song on the tenth day of the fourth lunar month of 1260. 69 Because the Song kept putting off receiving him, Hao Jing wrote a memorial to the Song government which says,

“[Our] court has actually sent two envoys, one to Koryô, the other to the Song. Even before our envoy has crossed the border, Koryô in response has sent two envoys, one celebrating [our Lord’s] enthronement, the other asking for restoring territory. Our Lord commended them and agreed. ... I have left the Lord’s Carriage for more than three months, and have been questioned for achieving nothing. In my humble opinion, if we lose this chance, border conflicts will occur again, and there will be endless war.” 70

This letter was written in the beginning of the seventh lunar month when Hao Jing had already arrived at the border of the Song. But he still kept following Koryô affairs and was well informed about the Wang Hûi mission. Hao Jing expressed his worry about the outlook of Mongol-Song relations by comparing the situation with the Song and Koryô. Nevertheless, the comparison itself also shows his gratification in the achievements of their policies toward Koryô.

Epilogue

As pointed out in the Introduction, the Mongol’s new policies toward Koryô cannot be attributed to the personal attitude of Qubilai. The discussions above have proved that the transition of Mongol-Koryô relations was not originally an intention of Qubilai, neither did it seem to be actively promoted by the Qahan himself. The primary driving force for a new pattern of abilateral relationship was the interactions between the scholar-ministers in Qubilai’s court and the Koryô missions.

There is still another question: how in the end would Qubilai have understood the status of the so-called eastern fan of Koryô? Two passages of Khublai’s words are revealing. The first was said to Wang Hûi on the banquet in 1260 comparing Koryô with the other “more than eighty states.” 71 The second was said to the Koryô king in 1270 comparing him with the Iduq of the Uyghurs and the Arslan Khan of the Karluks.

“Because you gave allegiance [to us] late, [in this assembly you] are arranged below the kings [of the Golden Lineage]. At the Cingis Qan’s time, the Iduq gave allegiance early, so was arranged above the kings; the Arslan Khan gave allegiance late, so was arranged below. You should understand this.” 72

It is quite clear that in Qubilai’s opinion, his favor to Koryô didn’t suggest a new framework for the interstate order, but rather a special treatment individually conferred within the tradition of the Mongol empire since Cingis Qan. In fact, Qubilai was not completely satisfied with the new policies. In the first lunar month of 1268, Qubilai expressed his dissatisfaction in person to a Koryô envoy, 73 and then issued the following edict:

“Our troops have been withdrawn as you had asked for. You promised to return-to-the-mainland in three years, but have failed to keep your words. It is the rule of Cingis Qan that all affiliated states must send hostage-princes, supply troops, provide provisions, establish jams, submit household registers, and accept daruqaci. I have had you notified clearly, but you have delayed until now without any commitment. … So, I am inquiring about this.” 74

In contrast to the tortuous and ambiguous texts of the Jinejie edict, this berating one was straightforward and really “the principles of my forefathers.” It is noteworthy that the Jingjie edict neither confirmed nor exempted the Six Obligations but skirted around this issue. If this later edict truly expressed Qubilai’s ideas, then what he had expected for this eastern fan should be far more than that of a ritual vassal under the tributary system. And reaffirmation from the Mongol side of the Six Obligations should be understood as an adherence to the Mongol tradition rather than any result of mutable character or preference of Qubilai.

In conclusion, Koryô-Mongol relations transitioned around 1260 in a multi-dimensional political network made up of diverse actors including Qubilai, his scholar-ministers, Koryô, and also other forces that have not been discussed in detail in this article. Qubilai’s consent to a settlement by negotiation was a precondition for the transition, while Koryô and the scholar-ministers in Qubilai’s court brought elements of the tributary system into the new Koryô-Mongol relationship. However, Qubilai himself still regarded Koryô as a subject favorably treated in the framework of his forefathers. Under a kind of ambiguity, the new elements had altered the Mongol tradition, but never replaced it. This further laid down at least part of the foundation for a relatively high degree of independence of Koryô under the Yuan empire. 75

Due to conflicts and adjustments between different cultural traditions of and cognitions on inter-state/regime orders, it is very difficult to define the status of Koryô under the Mongol-Yuan empire. Historians have proposed a variety of views such as tributary state (Chogongguk) 76, appanage (投下領) 77, affiliated state (Sokkuk) 78 and military ally. 79 This paper doesn’t intend to present a new concept, but only to underline the multi-layered and dynamic nature of the Mongol-Koryô relationship. It is inappropriate to regard it as either merely a return of the tributary system or a pure manifestation of general Mongol rulership. As David Robinson points out, it is vitally important to view Koryô within the context of both its local history and as part of a greater empire. 80 Morihira recognizes that at least part of the ruling elites of Koryô did acknowledge the Yuan as an orthodox dynasty of the Central Kingdom (中國). However, he defines it as, “the matter of cognition (認識上の問題)” which “should be strictly distinguished (厳密に区別すべき)” from “the matter of fact (本質上の問題)”, namely the actual rulership of the Mongols over Koryô. 81 However, from the discussions above in this paper, we could say that the Koryô ruling group and the scholar-ministers in Yuan did not submissively accept and whitewash all the decisions made by the Mongol Qahan, but actively affected the pattern of the Mongol-Koryô relationship from the very beginning under, at least partially, the framework of the tributary system. 82 Cognition and fact, though they may be epistemologically separate, are interrelated and interacted with each other in history.

Map 1

Wang Chôn’s Journey and the Political Situation in North China, 1259–1260

Abbreviations and Glossary

高麗史 KoryôSa (Chosôn-printed edition 奎章閣藏朝鮮刊本)

金史 Jin Shi (Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局, 1975)

元史 Yuan Shi (Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局, 1976)

References

1. Allsen Thomas. "The Rise of the Mongolian Empire and Mongolian Rule in North China." The Cambridge History of China: Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368. Franke Herbert and Twitchett Denis eds. pp 321–413. N.Y: Cambridge University Press, 2008.  2. Buell Paul. Historical Dictionary of the Mongol World Empire. Lanham and Oxford: Scarecrow Press, Inc, 2003.

3. Chen Dezhi (陳得芝). "Hubilie de Gaoli Zhengce yu Yuan-Li Guanxi de Zhuanzhe Dian(忽必烈的高麗政策與元麗關係的轉折點)." Yuanshi ji Minzu yu Bianjiang Yanjiu Jikan (元史及民族與邊疆研究集刊) 24 (2012): 70–80.

4. Han Sheng (韓昇). Dongya Shijie Xingcheng Shilun (東亞世界形成史論). Shanghai: Fudan University Press (復旦大學出版社), 2009.

5. Jiang Feifei (蔣菲菲)and Wang Xiaofu (王小甫). . Zhong Han Guanxi Shi:Gudai Juan (中韓關係史: 古代卷). Beijing: Sheke Wenxian Press, (社科文獻出版社). 1998.

6. Kang Chaegwang (강재광). "Ch’oe Ûi Chônggwôn ûi Taemong Hwaûinon Suyong kwa Ch’oe-ssi Chônggwôn ûi Punggoe(崔竩政權의對蒙和議論수용과崔氏政權의崩壞)." Hanguk Chungse Sa Yongu (한국중세사연구) 28 April;(2010): 521–56.

7. Kim Hodong (김호동). . Monggol Cheguk kwa Koryô: K’ubillai Chônggwôn ûi T’ansaeng kwa Koryô ûi Chôngch’ijôk Wisang (몽골제국과고려: 쿠빌라이정권의탄생과고려의정치적위상). Seoul: Seoul University Press, (서울대학교줄판부). 2007.

8. Ko Myôngsu (고명수). "Monggol-Koryô Kunsa Tongmaeng Kwangye: Yangguk Kwangye rûl Chomanghanûn Hana ûi Kwanjôm (몽골-고려군사동맹관계: 양국관계를조망하는하나의관점)." Yôgsawa Tamron (역사와담론) 88 October;(2018): 195–230.

9. Liu Xiao (劉曉). "Song Jinqing Chengxiang Shu Niandai Wenti Zai Jiantao: Jiantan Meng-Li Jiaowang zhong Biduchi de Diwei yu Yingxiang (〈送晉卿丞相書〉年代問題再檢討——兼談蒙麗交往中必闍赤的地位與影響)." Minzu Yanjiu (民族研究) 4 (2016): 79–87.

10. Liu Xiao (劉曉), Gaohua Chen (陳高華). "Yelü Chucai yu Zaoqi Meng-Li Guanxi: Du Li Kuibao de Liang-feng Xin (耶律楚材與早期蒙麗關係——讀李奎報的兩封信)." Wen Shi (文史) 1 (2002): 255–61.

11. Mao Haiming (毛海明), Fan Zhang (張帆). "YuanZhongyi ji ZhangYi Kao (元仲一即張易考)." Wen Shi (文史) 1 (2015): 199–217.

12. Matsui Dai (松井太). "Mongoru Jidai Uigurisutan no Zeiyaku S eido to Chōzei Shisutemu (モンゴル時代ウイグリスタンの税役制度と徴税システム) [Hikokutō Shiryō no Sōgōteki Bunseki niyoru Mongoru Teikoku-Genchō no Seiji Keizai Shisutemu no Kisoteki Kenkyū (碑刻等史料の総合的分析によるモンゴル帝国・元朝の政治・経済システムの基礎的研究)]." Kōichi Matsuda eds. pp 87–127. Report of the Scientific Research Project Grant-in-Aid JSPS, Basic Research (B)(1) (日本学術振興会科学研究費補助金·基盤研究(B)(1)研究成果報告書). 2002.

13. Morihira Masahiko. Mongoru Haken-ka no Kōrai: Teikoku Chitsujo to Ōkoku no Taiō (モンゴル覇権下の高麗―帝国秩序と王国の対応). N agoya: Nagoya University Press, (名古屋大学出版会). 2013.

14. No Kyehyôn (盧啟鉉). Koryô Oegyo Sa (高麗外交史).

Jing Zi (紫荆)

Rongguo Jin (金荣国)

. Yanji: Yanbian University Press (延邊大學出版社), 2002.

15. Robinson David. Empire’s Twilight: Northeast Asia Under the Mongols. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2009.

16. Rossabi Morris. Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 1988.

17. Sun Meng (孙勐). "Beijing Chutu YelüZhu Muzhi Jiqi Shixi Jiazu Chengyuan Kaolue (北京出土耶律鑄墓誌及其世系、家族成員考略)." Zhongguo Guojia Bowuguan Guankan (中國國家博物館館刊) 3 (2012): 49–55.

18. Wei Zhijjiang (魏志江). Zhong Han Guanxi Shi Yanjiu(中韓關係史研究). Guangzhou: Sun Yat-senUniversity Press(中山大學出版社), 2006.

19. Gaowa Wuyun (烏雲高娃). "Hubilie yu Gaoli Shizi Tian de Huijian ji Gaoli Huan Jiudu (忽必烈與高麗世子倎的會見及高麗還舊都)." Ouya xuekan(歐亞學刊) 9 (2009): 299–309.

20. Gaowa Wuyun (烏雲高娃). Yuanchao yu Gaoli Guanxi Yanjiu (元朝與高麗關係研究). Lanzhou: Lanzhou University Press (蘭州大學出版社), 2011.

21. Xiao Qiqing (蕭啟慶). "Hubilie Qiandi JiulüKao(忽必烈潛邸舊侶考)." Nei Beiguo er Wai Zhongguo: Mengyuan-shi Yanjiu(內北國而外中國:蒙元史研究). pp 113–143. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju 中華書局, 2007.

22. Yao Dali (姚大力) . Meng-Yuan Zhidu yu Zhengzhi Wenhua (蒙元制度與政治文化). Beijing: Peking University Press (北京大學出版社), 2012.

23. Yi Kaesôk (李玠奭). "Yô-Mong Hyôngje Maengyak kwa Ch’ogi Yô-Mong Kwangye ûi Sônggyôk (麗蒙兄弟盟約과초기麗蒙關係의성격)." Taegu Sahak(大丘史學) 101 November;(2010): 81–132.

24. Yi Yigju (이익주). "Koryô-Monggol Kwangye yesô Poinûn Ch’aegbong-Chogong Kwangye Yoso ûi T’amsaek (고려-몽골관계에서보이는책봉-조공관계요소의탐색)."

13–14 Segi Koryô-Monggol Kwangye T’amgu (13-14세기고려-몽골관계탐구)

. Northeast Asian History Foundation (동북아역사재단) and Institute for Studies on Korea-China Exchange of Kyungpook University (경북대학교한중교류연구원). Seoul: Northeast Asian History Foundation (동북아역사재단), 2011, pp 53–91.

25. Yun Yonghyôk (尹龍爀). "Chip’o Kim Kuûi Oegyo Hwardong kwaTae-Mong Yinsik (止浦金坵의외교활동과대몽인식)." Chônbuk Sahak(전북사학) 40 April;(2012): 5–31.

Appendices

Chronology

|

Year |

Lunar Month |

Lunar Day |

Events |

|

1258 |

12 |

29 |

The Pak Hûisil mission departed from Kanghwa. |

|

1259 |

4 |

21 |

The Wang Chôn mission departed from Kanghwa. |

|

7 |

21 |

Möngke died in Sichuan. |

|

leap 11 |

ca. 10 |

Wang Chôn met Qubilai at Bianliang. |

|

1260 |

2 |

? |

Wang Chôn left Yanjing. |

|

3 |

20 |

The Wang Chôn mission returned to Kanghwa. |

|

24 |

Qubilai ascended the throne at Kaiping. |

|

28 |

Conversation between Saridai and Wang Chôn. |

|

4 |

9 |

Jing Jie delivered an edict from the Mongol. |

|

10 |

Hao Jing was sent for negotiation with the Song. |

|

24 |

Kitadai delivered an edict from the Mongol. |

|

29 |

The Wang Hûi mission departed from Kanghwa. |

|

6 |

? |

The Wang Hûi mission arrived at Kaiping. |

|

14 |

Conversation between Saridai and Kim Pojông |

|

7 |

? |

Hao Jing wrote a memorial to the Song, mentioning two envoys from the Koryô. |

|

8 |

8 |

Saridai delivered an alleged oral instruction from Qubilai. |

|

17 |

The Wang Hûi mission returned to Kanghwa. |

|

1261 |

3 |

15 |

Wang Wentong was appointed to compose a reply letter to some Koryô mission. |

|

6 |

10 |

The Wang Sim mission arrived at Kaiping. |

|

|